India’s power deficit isn’t as dire as you’d think

It’s been a sweaty summer of powerless days—and nights—in India.

It’s been a sweaty summer of powerless days—and nights—in India.

Expectedly, there have been protests on the streets of New Delhi, chaos in state legislatures and even predictions of how India’s power crisis could derail prime minister Narendra Modi’s ambitions for economic growth.

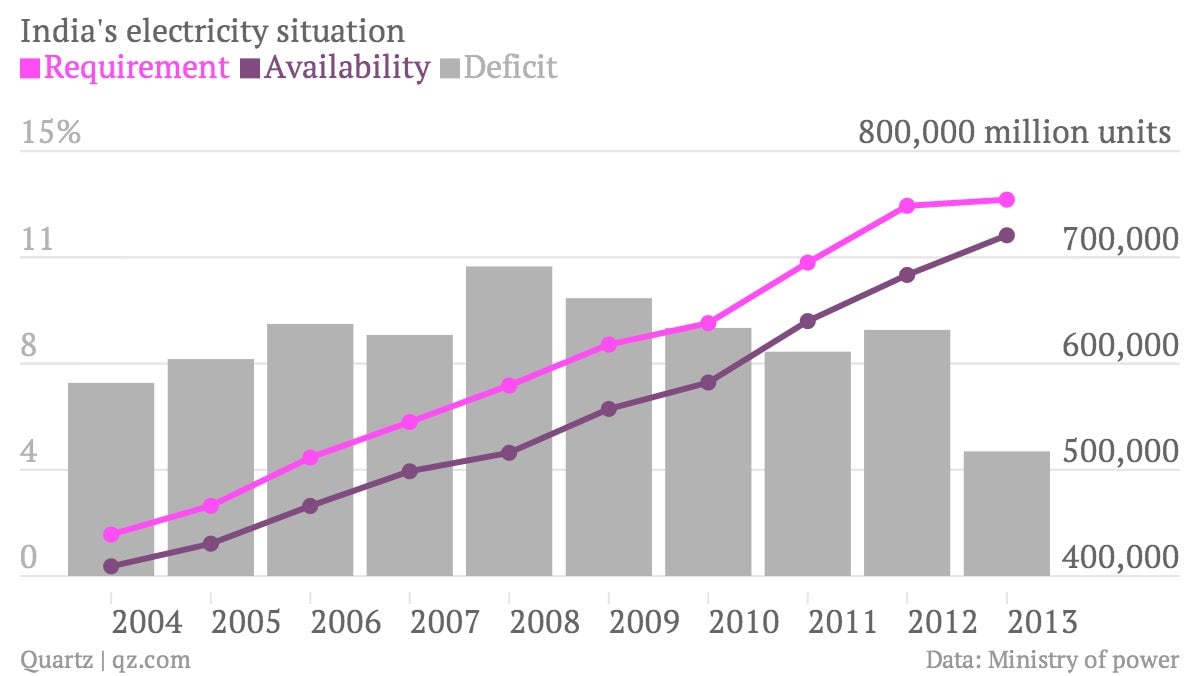

But this actually isn’t an endless mess without any signs of improvement. A different story unfolds in the analysis below of power requirement, availability and the deficit for April-December annually from 2004 to 2013.

India’s power requirement has zoomed, nearly doubling in the last decade, with two periods of relatively sluggish growth. First, shortly after the global financial crisis erupted, in 2009 and then more recently between 2012 and 2013.

Through most of this period, power availability has struggled to keep up with demand, posting its worst deficit in 2008. Of course, fast growing economies often find it difficult to ensure a perfect demand-supply equilibrium. And, in India there have been repeated questions over whether economic growth would be hit because of a stalled power sector.

But things suddenly changed in 2013, with the deficit falling to under 5% for the first time since 2004. This could be partly a consequence of the UPA government’s push for increased generation during the end of its term, including setting up a committee to monitor the sector.

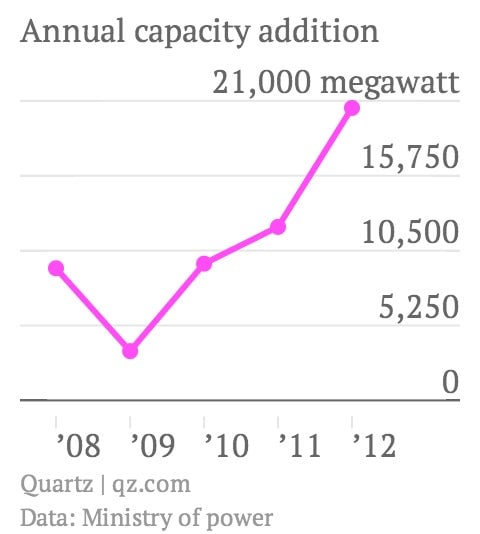

In the last decade, India’s installed power capacity has also jumped 108% from 112,700 megawatt in 2004 to 234,600 megawatt in 2014, although annual capacity addition significantly dropped in 2009. Since then, the numbers have steadily improved.

“In 2012-13 and in the nine months of the current financial year, we have added 29,350 megawatts of power capacity,” former finance minister P. Chidambaram said in his interim budget speech (pdf) in February this year.

There’s also 50,000 megawatt of thermal and hydro power capacity under construction, according to Chidambaram, along with assured coal supply for 78,000 megawatt of thermal power capacity. Despite all this, the forecast for 2014 is that the deficit will remain around 5.1%.

While that isn’t ideal, it’ll still be lower than 6.82% deficit that the Manmohan Singh government faced in 2004. And how it moves subsequently, will, of course, depend on the new government’s direction for the sector. They, after all, are the ones with the power to actually do something.