Sadananda Gowda reversed an incorrigible trend—lavishing sops on the rail minister’s constituency

Early in his maiden railway budget, railways minister D. V. Sadananda Gowda announced that he wasn’t one for populism. Instead, he took time to draw out the legacy of his predecessors who helmed India’s largest transportation network.

Early in his maiden railway budget, railways minister D. V. Sadananda Gowda announced that he wasn’t one for populism. Instead, he took time to draw out the legacy of his predecessors who helmed India’s largest transportation network.

“There has been focus on sanctioning projects rather than completing them,” Gowda said. The numbers say as much. Six hundred and seventy six projects have been sanctioned in the last three decades, amounting to Rs1,57,883 crore ($26.44 billion). And as it stands, only 317 projects have been completed, with the rest likely to cost an estimated Rs1,82,000 crore ($30.46 billion). That’s more than the original estimates for all projects.

“In the last 10 years, 99 New Line projects (adding new lines, as opposed to track doubling) worth Rs60,000 crore were sanctioned, out of which only one project is complete till date,” the minister added. Of course, that entire period effectively covers two terms of the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government.

A lot of these projects were commissioned for one reason—rail ministers like to commission projects in their home states and constituencies. It’s an investment towards securing their own political future. When they leave office, the next rail minister rarely allocates money to it, and thus the railways is saddled with a large number of unfinished projects.

Consider the largesse—both new projects and new trains—doled out to home constituencies in the last five railway budgets.

Mamata Banerjee (2009): “The old mindset of economic viability should be substituted by social viability,” Banerjee told India’s Parliament, fresh from victory in the 2009 general elections. And so, the Trinamool Congress chief kept her first railway budget on the populist track, with a large helping for her home state of West Bengal.

For her state alone, she announced a 1,000 megawatt power plant at Adra, a coach factory at the Kanchrapara-Halisahar Railway complex, investments in rolling stock production, assembly facilities and coach rehabilitation at Dankuni, Majerhat and Naopara. The eastern freight corridor was also to be expanded up to Dankuni.

It didn’t end there. Out of the 309 stations proposed to be developed as model stations, at least 142 were in West Bengal, and about 22 of the 53 rail connectivity projects were for the state.

Mamata Banerjee (2010): Her second railway budget took off from where the first ended—complete with 14 mentions of ‘Kolkata’. With an eye on the impending assembly elections in West Bengal, Banerjee gave the state a coach factory, diesel multiple unit (DMU) manufacturing facility and and a rail axle factory. There was also a sports academy, two museums and a cultural centre thrown into the mix alongside multiple training and research facilities.

Mamata Banerjee (2011): Just months before the landmark elections where she decimated the Left, Banerjee did what all wily politicians tend to do: Keep rates untouched, and announce a slew of projects. And so, she kept passenger and freight rates constant, and let the goodies flow. Despite two years of pampering that yielded little, West Bengal was given a rail industrial park, a track machine factory and a handful of training centres.

Kolkata—mentioned no less than 16 times—got 50 more suburban train services. The Kolkata Metro got 34 new services, alongside plans to setting up a seemingly complex integrated suburban railway network, and Kolkata Rail Vikas Nigam. Most of it stayed just that—plans.

Dinesh Trivedi (2012): With Banerjee taking office as West Bengal chief minister, her lieutenant from Barrackpore took over the railway ministry. Unfortunately for the reform-minded Trivedi, it didn’t end well after his party chief sacked him because he dared to raise fares.

Despite his seeming fiscal discipline, Trivedi showered Bengal with unusual affection. This included a coaching terminal, a propulsion system factory, training centres, 15 new express trains, a bunch of new services for suburban trains and the Kolkata Metro—and a 72 megawatt windmill.

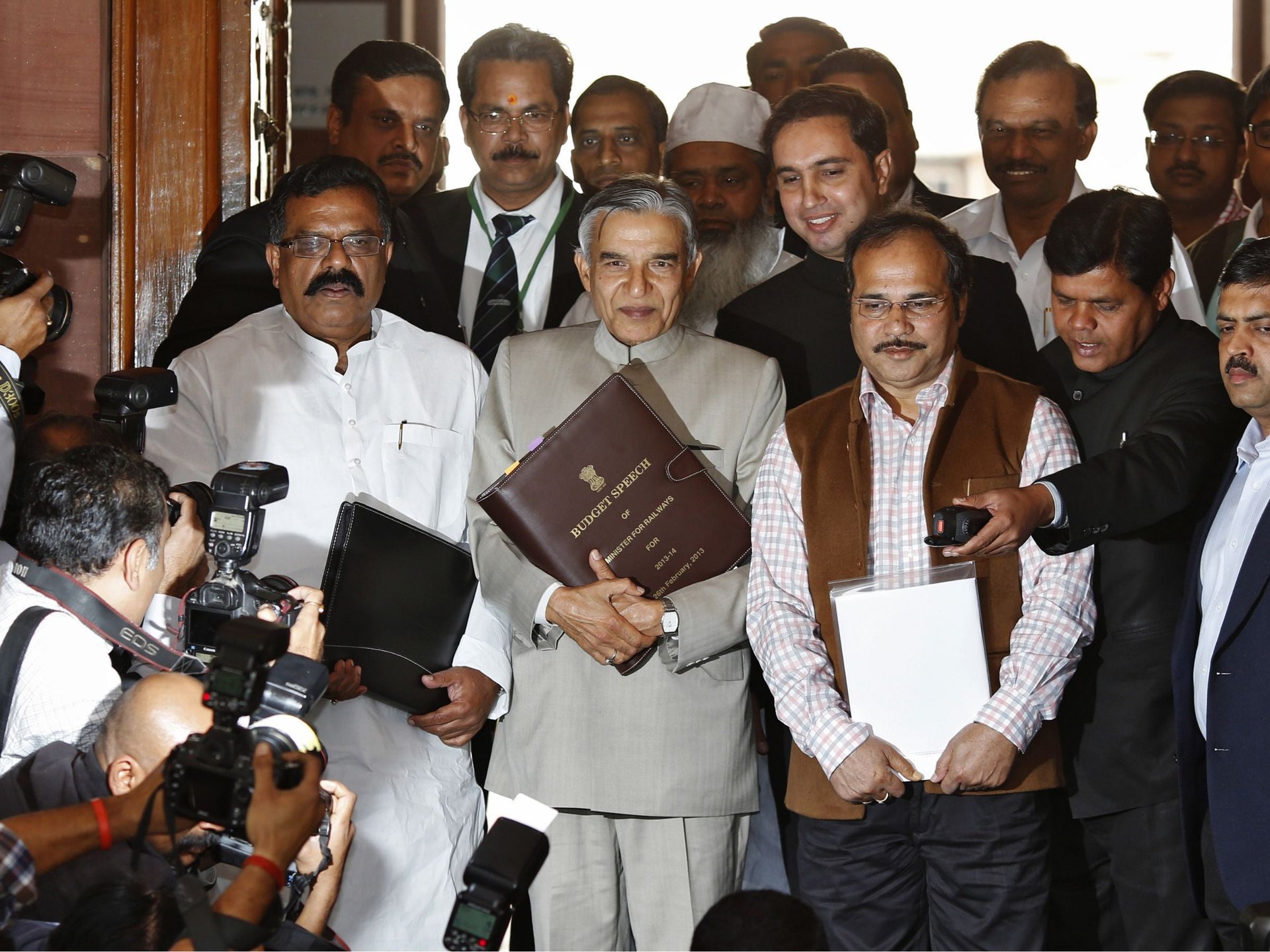

Pawan Kumar Bansal (2013): Caught in a whirlwind of corruption, Bansal was the first Congressman to helm the railway ministry since the turn of the decade. And he didn’t disappoint his constituency—Chandigarh.

Looking to appease both Punjab and Haryana, he announced a coach manufacturing unit, skill development centres, doubling of tracks, new lines and at least seven trains going through Chandigarh.

Gowda, however, was the most disciplined in this aspect. He announced merely four new express trains for his state, apart from three pairs of electric trains originating from Bangalore.

“I also can get claps from this august house by announcing many new projects, but that would be rendering injustice to the struggling organisation,” he said.

But then, he went on to play an ultimate crowd-pleasing move—a bullet train between Mumbai and Ahmedabad.

It didn’t go down well with the opposition.