This one chart starkly explains why India needs foreign investment in defence

Even by the ritualistic standards of Indian politics, it’s become a well-oiled ceremony—any proposal for change in the status quo of India’s defence procurement or manufacturing is immediately met with cries of protest.

Even by the ritualistic standards of Indian politics, it’s become a well-oiled ceremony—any proposal for change in the status quo of India’s defence procurement or manufacturing is immediately met with cries of protest.

Finance minister Arun Jaitley’s budget proposal to raise the limit of foreign direct investment in defence production to 49% was the latest—and it has predictably stirred consternation.

Former defence minister AK Anthony has warned that Indian defence firms will resultantly come under the control of multinational corporations, while Jaitley has sought to allay concerns about security.

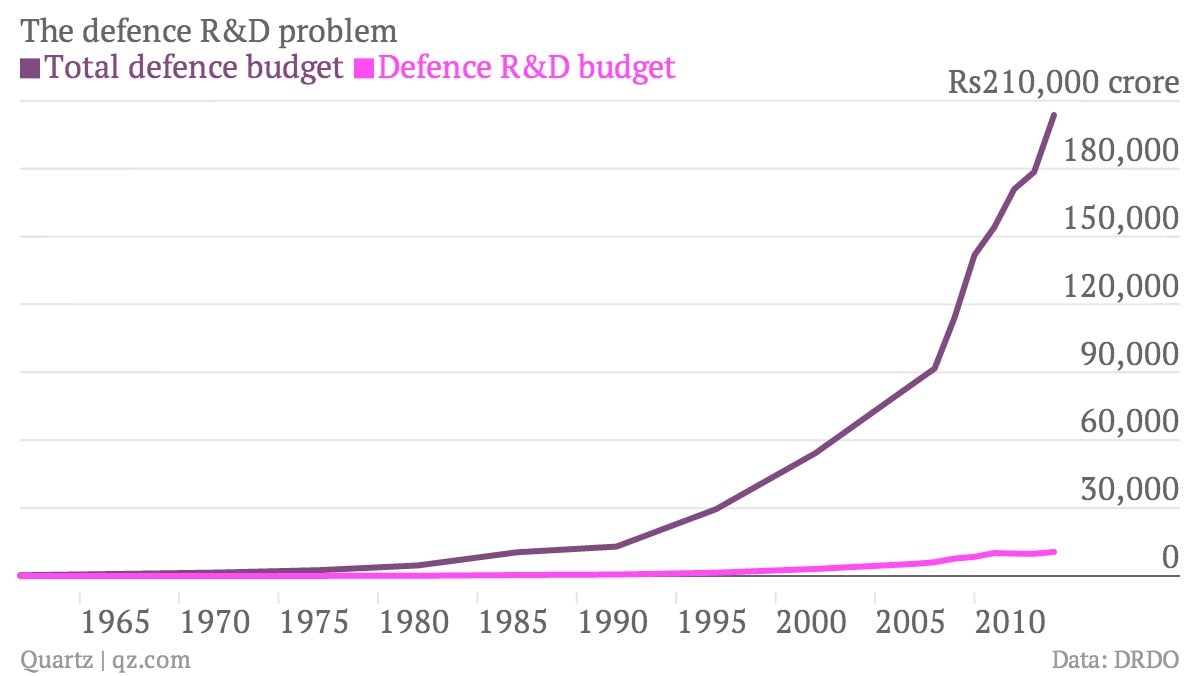

But here’s a single chart that makes the case for more FDI in India’s defence sector.

The fact is that India—the largest arms importer in the world—spends precious little on research and development (R&D), and it’s only getting worse.

The proportion of the defence budget received by the Defence Research & Development Organisation, the Indian defence ministry’s main R&D arm, has dropped since 2008.

A 12% increase in the defence budget for 2014-15, however, might stem that fall if more money flows into R&D.

But compared to global military powers, it still likely won’t be enough. The United States spends about 11% of its defence budget on research, development, testing and evaluation, while Russia allocates about 7%.

And although China doesn’t provide specific numbers, Craig Caffrey, a senior analyst at IHS, reckons it spends about 6%—or $11 billion—on defence. India’s defence budget is only about a third of China’s.

Part of the India’s defence industry’s problem is that it doesn’t have the entire set of capabilities required to execute high-end development programs. That’s where opening up the industry could be useful.

“If Indian organisations were to partner with more experienced foreign companies in some of these projects then that technical expertise could probably be leveraged more easily and in turn Indian industry would gain the expertise needed to eventually pursue these kind of complex R&D programmes independently,” Caffrey explained.

The Indian government, of course, remains concerned about Indian firms losing control to foreign enterprises, although it remains reluctant to put more money into developing its industry. Not that the country’s private sector has stepped up to make large investments either. The industry blames this on lack of a clear policy and visibility on potential returns.

And even if the government ploughed in more money, it’s unclear whether India’s state-owned defence establishment—consisiting of the DRDO, eight public sector enterprises, and 40 ordnance factories—would be able to effectively utilise (pdf) such investments.

So, India can either choose to continue spending billions to buy its military hardware, or open up its defence industry further to start work on manufacturing the stuff its armed forces actually need. If his campaign speeches are any indication, PM Modi will push in the latter direction. Both during his campaign as well as after assuming power, he has talked about the need for India to become a net exporter of arms.