Why the West is now doing what my Indian grandfather did in the mid-1900s

During the mid-twentieth century in India, my grandfather did something that was not unheard of—he selected the careers of his six sons. In accordance with what he thought were their strengths and what he believed to be respectable occupations that would enable them to provide well for their families, he decided two should be engineers, two should be doctors, and two should be accountants. And so it was written and so it was done.

During the mid-twentieth century in India, my grandfather did something that was not unheard of—he selected the careers of his six sons. In accordance with what he thought were their strengths and what he believed to be respectable occupations that would enable them to provide well for their families, he decided two should be engineers, two should be doctors, and two should be accountants. And so it was written and so it was done.

Cut to Canada and the later twentieth century. I had an indulgent father. When, after trying to find myself, I did an undergraduate in psychology, my grandfather was perplexed. It was only after I accidentally strayed into an MBA that I somewhat redeemed myself in his eyes and his worries over my future reduced.

The east and west were very different in this respect and understandably so.

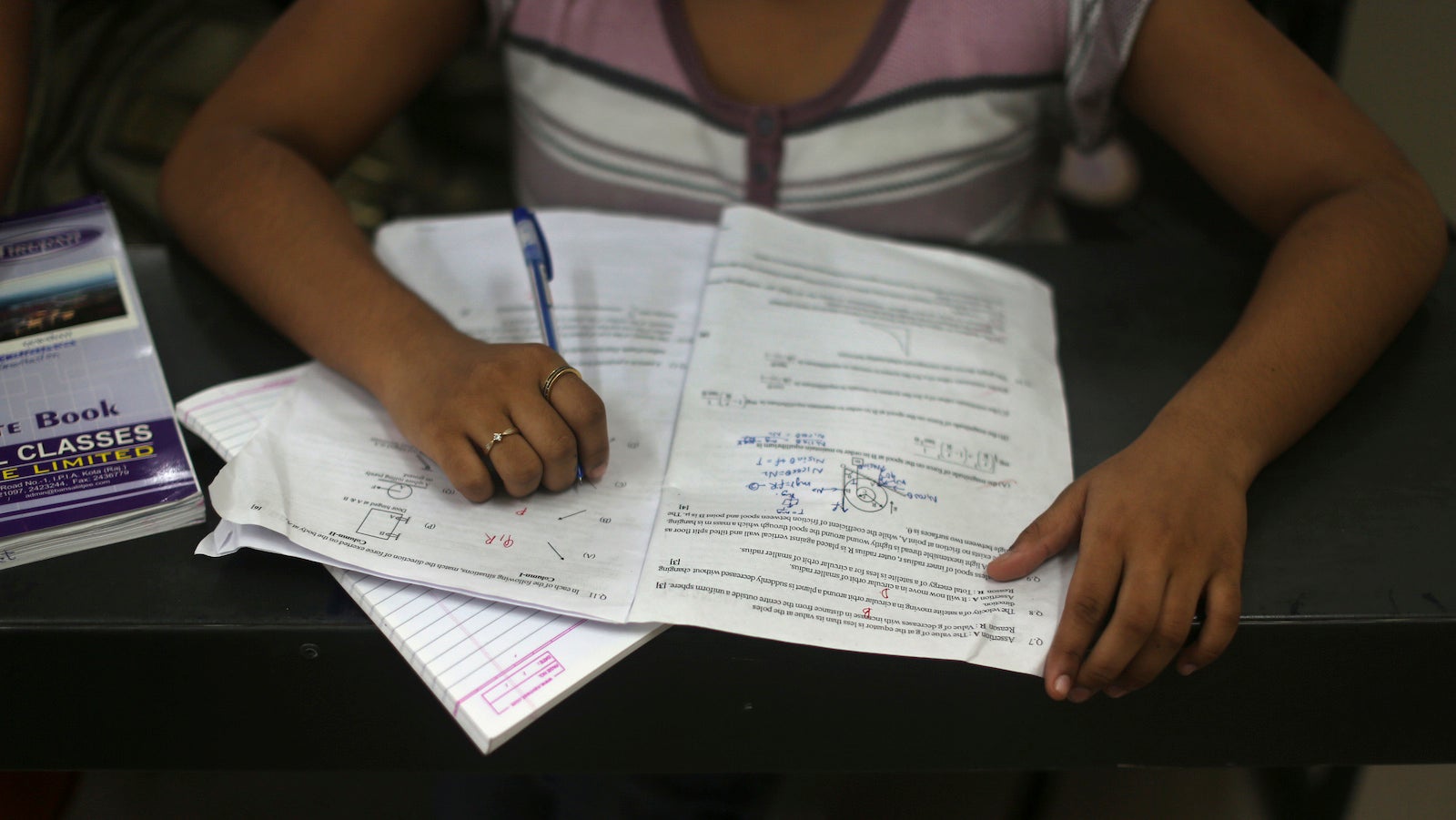

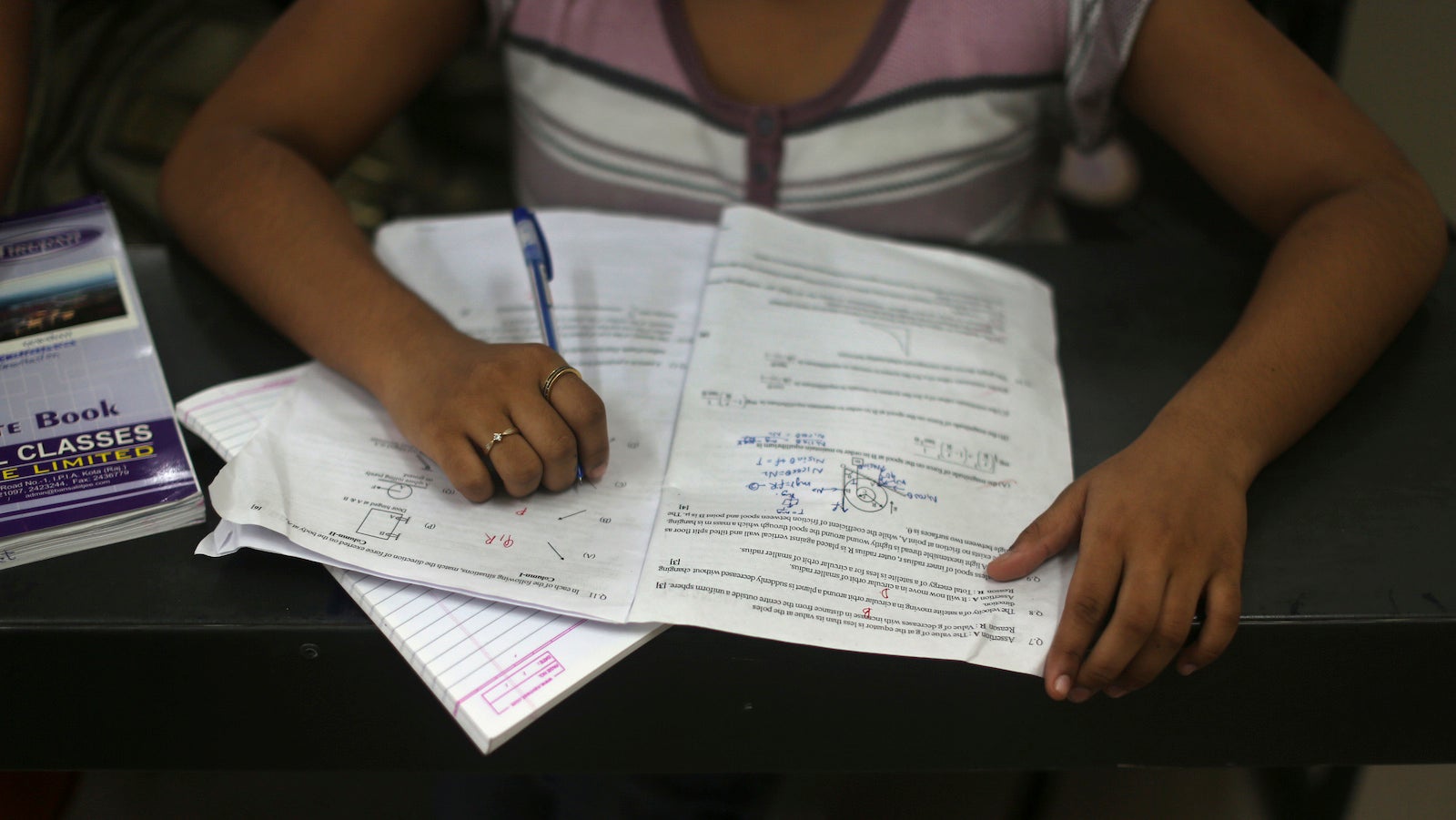

In recently independent India, leaders with goals of industrialisation were promoting technology and science, and setting up institutions like the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and the Indian Institutes of Technology. Careers were selected not by individual interest but rather by what you were capable of and what could afford you the best living. In a densely populated country with limited opportunities and vast inequalities, this strategy seemed the best route if not to prosperity then at least to a sustainable future. Beginning early in school, science and math were given the greatest prestige. Later, the smartest youngsters were channeled into engineering and medicine. In the hierarchy, next came the pure sciences, headed by physics. Then any math-related commerce courses, like finance and accounting. The rest had to make do with the humanities.

An equal society

Canada however already had all the fruits of the industrial revolution and a high standard of living. Life was good and looked as though it would only improve for each successive generation. In a country where a university professor may well be living next door to a plumber, the struggle to get specifically into engineering school did not seem worthwhile. After all, both professor and plumber could afford a car, a house, and yearly vacations, and probably both sent their kids to the same government-funded neighbourhood school. Most tellingly, both were accorded equal respect by society and were likely friends on a social level too. No doubt, this is a sign of a more affluent and equitable society where all forms of work were evenly valued.

Now, both east and west, seem to be shifting their attitudes.

Western newspapers and magazines are brimming with talk of STEM courses—meaning Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. While the Council of Canadian Academies is assessing the nation’s status in STEM skills, the Canadian government is funding a Youth STEM Initiative to encourage school children to pursue careers in STEM fields. The US Department of Education has a national strategy to increase the number of graduates in STEM fields , assisted by NGOs such as the STEM Academy and Project Lead The Way. Even the Boy Scouts have gotten into the act; in both countries, the organization is rolling out an awards program to raise interest in the STEM fields. The UK has already established a National STEM Centre which promotes STEM education in schools and colleges, as well as supports careers in STEM fields. The Guardian newspaper reports that during 2013-14, a record number of students were accepted into undergraduate STEM courses in the UK.

Suddenly in the West, nerdy means cool. STEM equals success, or at least employment. STEM courses seem to help both the individual as well as the national agenda. The individual is more likely to get a job and earn well—essentially what my grandfather wanted for his sons. And with more such individuals, the country hopes to be more competitive on the global platform.

Meanwhile, in India, newspapers are printing articles about alternate careers. The ‘engineering or bust’ mentality is no longer all-pervasive among kids. We’re beginning to hear of youngsters going—not because of lack of option but willingly—into the humanities, not to mention into careers that were absolutely off the map just a few years ago, like modelling and DJ-ing and the arts. And upon hearing such news, not all parents are thinking of it as economic suicide, not all friends are immediately offering their condolences, and not all of society is labelling them as social pariahs. Suddenly in the East, it’s okay not to be an engineer or even to try to be an engineer.

Calculus and economic confidence

The focus or lack of focus on STEM courses seems to be a reflection of a nation’s economic confidence.

In a country ascending in economic power, the people are open to taking more risk. Over the last 20 years, India has been experiencing high annual growth rates—sometimes up to 9%—and over that course has developed a thriving middle-class. An ascending country can afford to let its people to do what they want and they, bolstered by increasing affluence, can give rein to their individualism. Although India still has a long ways to go, it’s better off enough to no longer insist that everyone must be an engineer, scientist, or mathematician. Its youth feel that they have the luxury to look outside the fields of STEM.

However, in a country descending in economic power and growing in inequality, it makes strategic sense to retrench and go back to the basics. For example, the US has experienced a long recession and been involved in several expensive wars. And although it is still a superpower, its supremacy is threatened enough to begin active promotion of STEM courses. Enrolment in these courses have been on a steady decline there. A country in an economic downturn needs to provide its people with more guidance—just as perhaps in times of economic constraint, a father needs to help decide what’s best for his sons. That guidance could be towards a path that will be good for the nation as a whole and individual interest may need to give way a bit to group welfare.

And that may not all be bad. As India—a country that has long idealized STEM courses and is also at home with the concept of arranged marriages—can well understand, it is possible to come to love the career that is picked for you—especially if it comes with more employment opportunities, greater status, higher pay, and a better life.