These charts answer an age-old question—can money win you elections in India?

Even before the heat and dust had settled, it was clear that the 2014 general elections was going to be the most expensive in the history of India.

Even before the heat and dust had settled, it was clear that the 2014 general elections was going to be the most expensive in the history of India.

Now, as political parties begin to file their expenditure reports with the Election Commission of India, the impressive scale of the spending is becoming clearer.

The data reveals how running a political party in India is a bit like managing a team in Europe’s football leagues or Formula One racing—spending is a necessary but insufficient condition for a win.

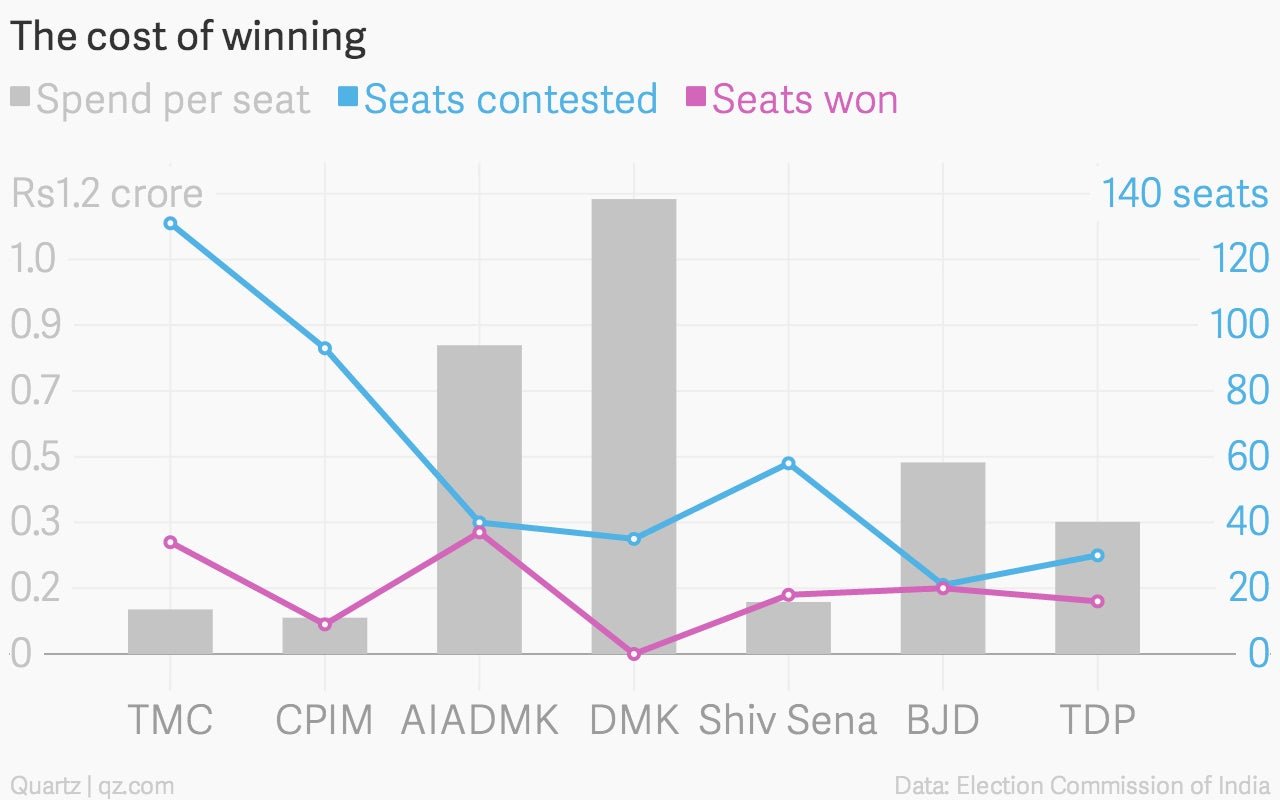

The following chart shows how there is little correlation between spend per seat (total expenditure divided by the number of seats contested) and the number of seats won. These are among the best performing parties in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls, excluding the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress, which still haven’t filed their expenditure reports. Also included below is the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), which despite its dismal performance is a big spender.

(BJD stands for the Biju Janata Dal, TDP is the Telugu Desam Party)

At the frugal end of the scale is Maharashtra’s Shiv Sena, which says it spent only Rs7.8 crores to contest 58 seats. Out of these, it won in 18.

That’s a stellar success rate compared with the DMK, which pumped in Rs41.51 crores across 35 seats and won absolutely nowhere.

These are, of course, only the official expenditure reports that are filed by political parties. It’s widely acknowledged that there is a vast pool of unaccounted funds that power these electoral campaigns. Still, the filings with the Election Commission give an inkling of the monetary wherewithal behind these parties. These amounts went into funding campaigns in addition to the money spent by individual candidates, which are capped by Election Commission norms based on a matrix that factors in location and population of constituencies. There is no limit on how much money a party can spend on an election.

Those advocating for reform of campaign funding have long held that Election Commission’s spending limits are unrealistic and end up being a source of illegal and opaque election funding, setting off a cycle of corruption that runs through the tenure of an elected representative.

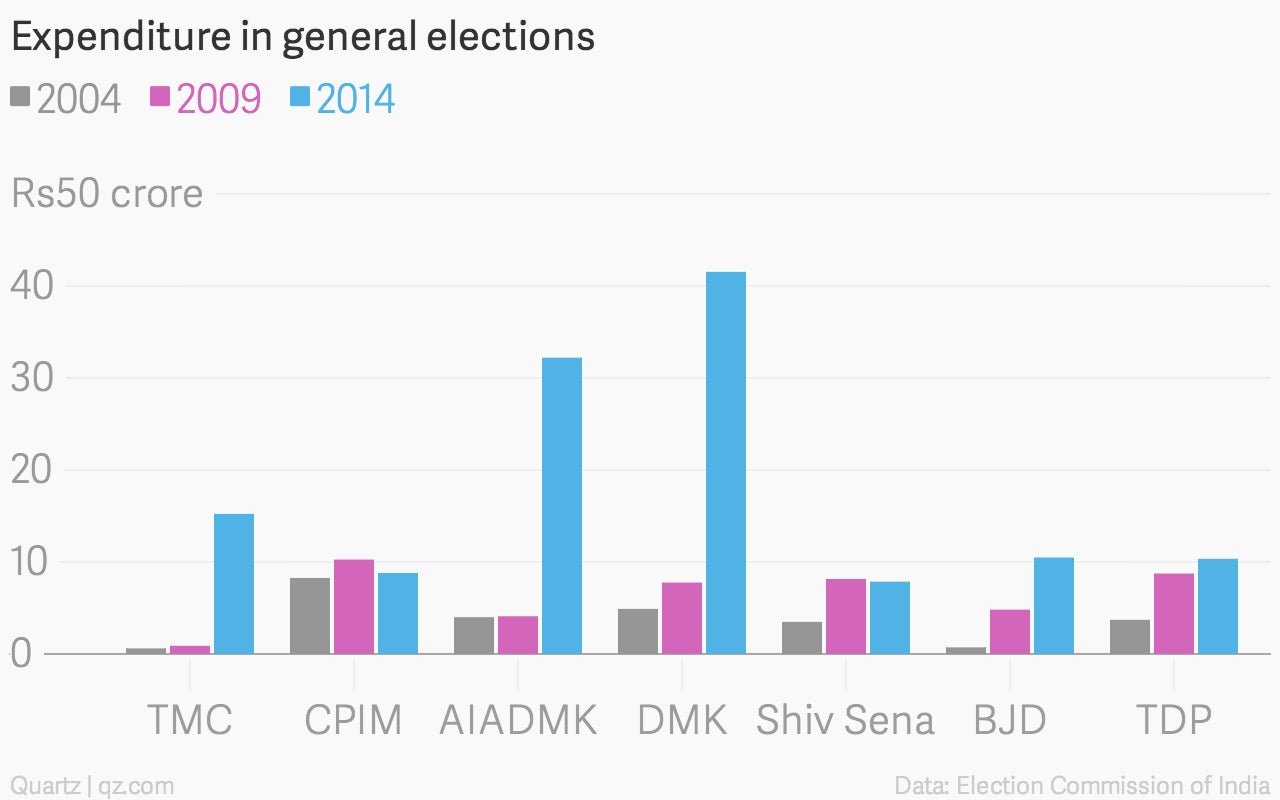

The Trinamool Congress (TMC), currently the ruling party in West Bengal, has seen its fortunes rise after it came into power in 2011, ending the uninterrupted 34-year rule by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Between 2009 and 2014, the TMC’s election war chest grew strongly, as did the expenditure by Tamil parties, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) and the DMK.

Currently, though, the leaders of both the TMC and the AIADMK—Mamata Banerjee and Jayalalitha—are being troubled by allegations of corruptions. Banerjee is fending off accusations of impropriety in the Saradha scam, while Jayalalitha has had to step down as chief minister of Tamil Nadu after she was convicted in a disproportionate assets case.