The fate of these Indian prisoners in Pakistan’s jails hangs on the power of crowdsourcing

India is facing a strange and difficult problem across the border in Pakistan: There are 22 prisoners lodged in Pakistani jails who are believed to be Indians, but the Indian high commission in Islamabad has been unable to ascertain their nationality and place of permanent residence.

India is facing a strange and difficult problem across the border in Pakistan: There are 22 prisoners lodged in Pakistani jails who are believed to be Indians, but the Indian high commission in Islamabad has been unable to ascertain their nationality and place of permanent residence.

Seeking answers, the Indian government has decided to crowdsource the problem.

On Oct. 16, New Delhi’s mission in Islamabad posted an appeal for information on its website, along with a list of the 22 prisoners that included their photographs. Contact details of two Indian diplomats, one in New Delhi and another in Islamabad, were also provided. “The high commission of India has not been able to establish the national identity of these individuals in the absence of sufficient detail and information of their background and place of permanent residence,” it said.

The 22 prisoners—ranging from 21-year-old Ramesh to 54-year-old Rasse-Ud Din—include only four women, and very little seems to be known about them. The list has a hearing-impaired individual without speech who is unnamed. “Mark of Aum (Om) on the back of his right hand’s palm,” is the only detail available, alongside a photograph and approximate age between 45 years and 50 years.

There is one prisoner listed without any name or other details—just a photograph.

Hundreds imprisoned

These 22 prisoners are among the approximately 400 Indians incarcerated in Pakistani jails, according to information provided by the ministry of external affairs to India’s Parliament between 2013 and 2014. And 385 Pakistanis are believed to be held in Indian prisons, two Indian and Pakistani non-profit groups together estimated earlier this year.

A large number of these prisoners, in both countries, include fishermen—107 Pakistanis (pdf) in Indian jails and 249 Indian fishermen held Pakistan. And this is after more than a hundred Indian fishermen were released by Islamabad immediately preceding Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif’s visit to New Delhi for the oath-taking ceremony of his Indian counterpart in May 2014.

Others include cattle herders, who are arrested and jailed by both sides for inadvertently straying across the international border or the Line of Control between India and Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir. And then there are spies allegedly sent by the security establishments of both countries, always disowned and abandoned if they get arrested across the border.

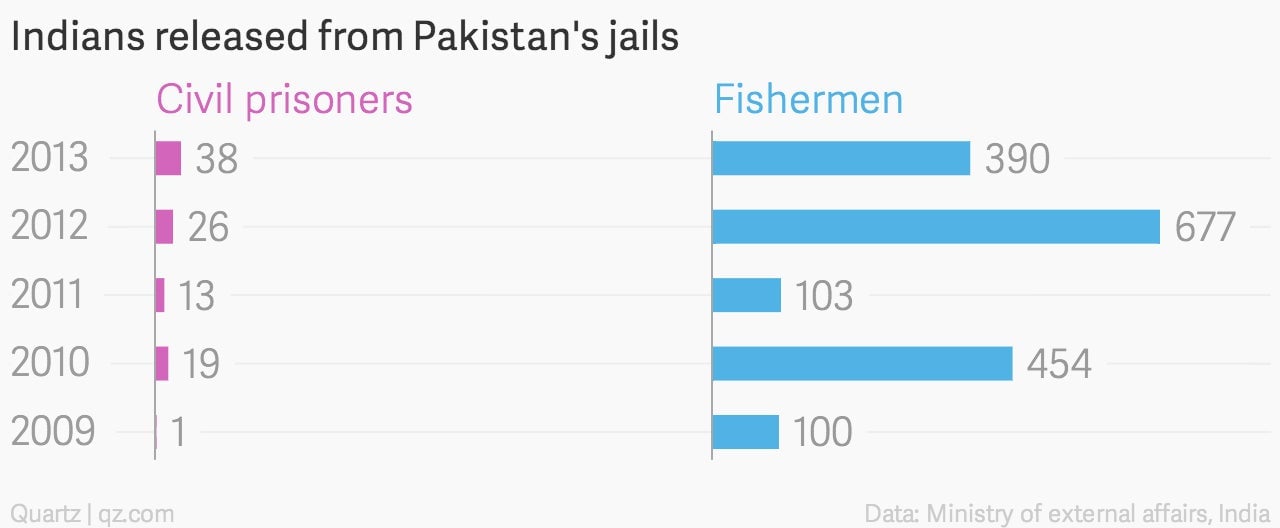

Over the last five years, the number of Indians released—the Indian government counts civil prisoners and fishermen separately—has varied, according to the ministry of external affairs, although increasing numbers of Indian civil prisoners have been freed.

Since 2007, an India-Pakistan Judicial Committee on Prisoners, comprised of former judges, has been working to identify and help release prisoners on both sides of the border.

Yet, the committee could do little to release Sarabjit Singh, an Indian national who died in May 2013, six days after he was stabbed by fellow inmates in Lahore’s central jail. Accused of being involved in a series of bomb blasts in 1990, Singh had reportedly spent over two decades in Pakistan’s jails.

Indians jailed elsewhere

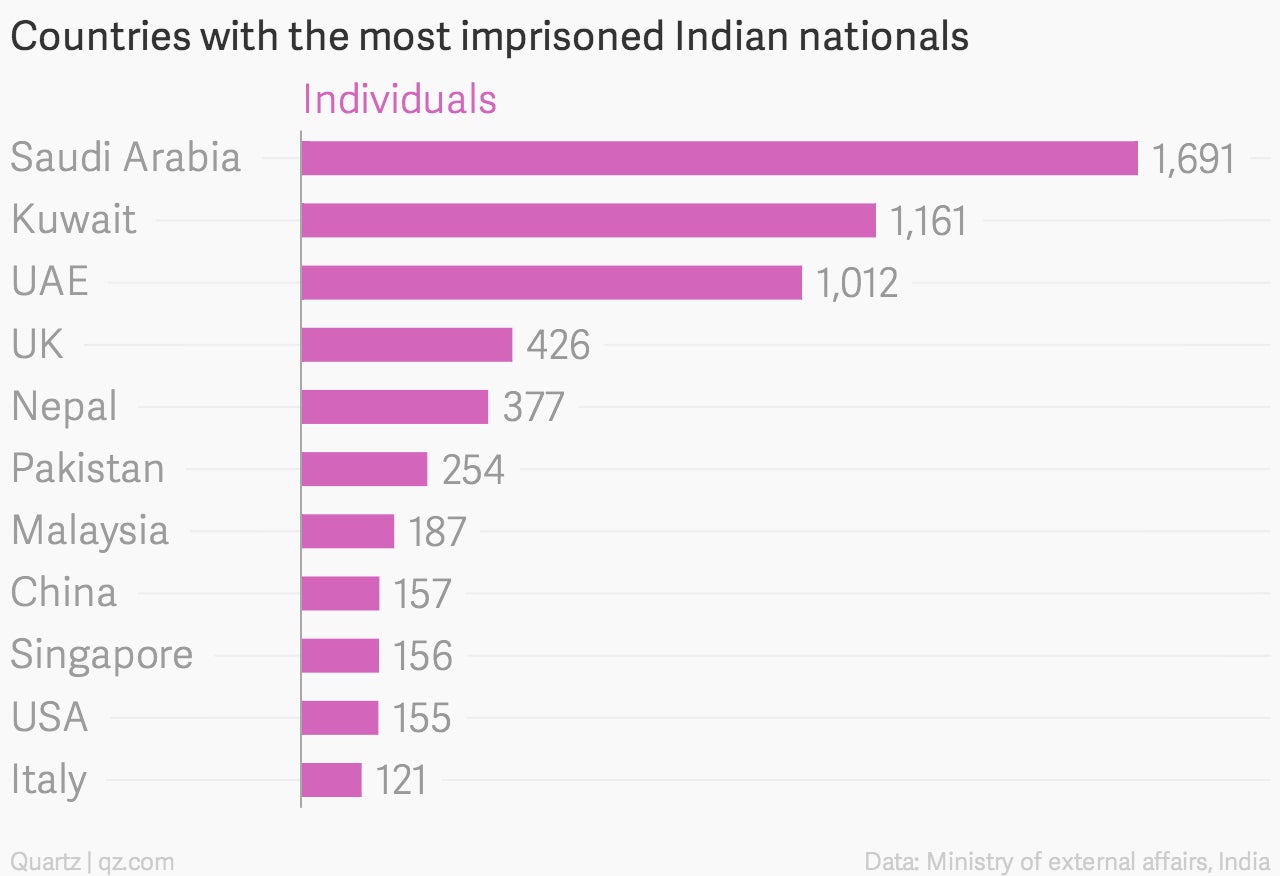

Pakistan, however, doesn’t hold the most number of Indians imprisoned abroad. Of the 6,569 Indian nationals (as of 2013) incarcerated around the world, three countries in the Middle East—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—have the biggest share.

Over 5.5 million Indians live and work in the Gulf countries, sometimes in inhuman and unfair conditions, and send back over $32 billion in remittances to India.

Thousands, evidently, also end up on the wrong side of the law.