Why India needs a bank that loans to beauty parlours and kitchens

In August, prime minister Narendra Modi launched the Jan Dhan Yojna (people’s wealth scheme), with an aim to ensure a bank account for every household in India—a landmark initiative in a country where millions of families have mobile phones, but no bank accounts.

In August, prime minister Narendra Modi launched the Jan Dhan Yojna (people’s wealth scheme), with an aim to ensure a bank account for every household in India—a landmark initiative in a country where millions of families have mobile phones, but no bank accounts.

But it isn’t the only ambitious plan that was put into motion in the last 12 months to end “financial untouchability” in the country.

In Nov. 2013, the former prime minister Manmohan Singh inaugurated the country’s first ever state-owned bank for women to economically empower millions of Indians across the country who had been cut from even basic financial services—such as bank accounts or loans—for too long.

On Nov. 19—also the birthday of India’s only woman prime minister Indira Gandhi—this bank will complete its first year of operations.

Report card

The Bhartiya Mahila Bank (BMB), which started with an initial capital of Rs1,000 crore ($161 million), loans mostly to women, but accepts deposits from everyone. In the last year, it has opened 32 branches across the country, and has set a deposit target of Rs1,000 crore and a lending target of Rs800 crore for the current fiscal year. More than 80% of its 70,000 customers are women and almost 60% of the people employed by the bank are also women.

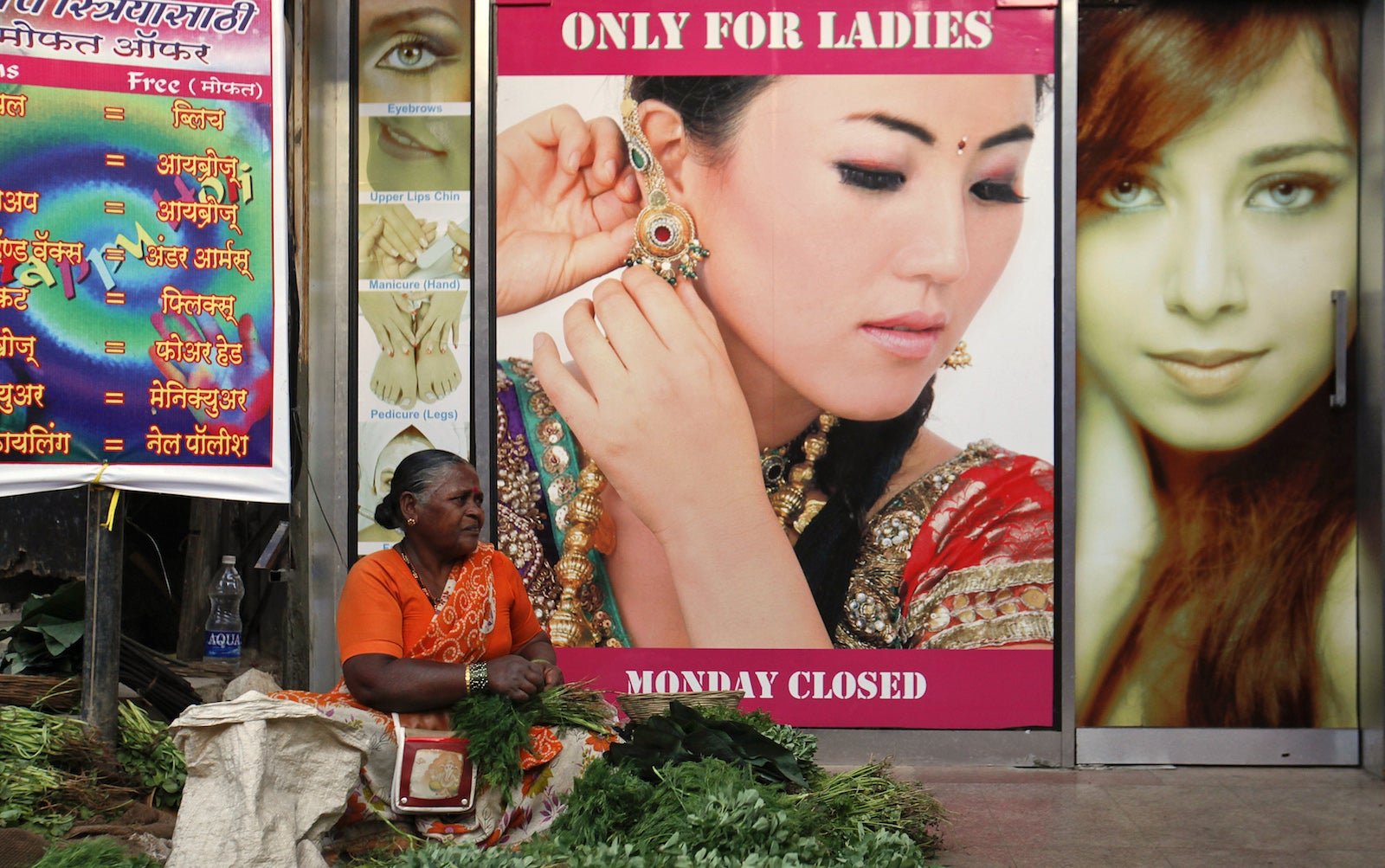

Such a bank in Asia’s third-largest economy makes much sense, since only 26% women have an account with a formal financial institution, compared to 46% of men. The banks serves not just millions of poor women who are at the bottom of the economic pyramid, but also entrepreneurs, CEOs and other urban professionals.

“Even when highly educated women go to a bank, they are treated with indifference,” said Usha Ananthasubramanian, chairperson and managing director of BMB, who has worked in the banking industry for over three decades. “Banking as a business is seen as a man’s forte.”

According to the bank’s website, the institution “has designed many women-centric products keeping in mind the core strengths of women so as to enable them to unleash their hidden potentials, engage in economic activities and contribute to the economic growth of the country.”

These “women-centric products,” rather stereotypically, include loans to start businesses such as beauty parlours, child day care centres or catering services. The bank even has a “Kitchen Modernization Loan,” where a loan amount of up to Rs5 lakh is given to help women renovate their kitchen.

It seems limiting to assume that women would borrow money mainly to redo their kitchens or start a beauty salon. But the bank’s chairperson believes that such loans reflect the reality of the day.

“Women are generally into small businesses and they usually need Rs20-25 lakh to start with,” Ananthasubramanian told Quartz. “They don’t really want to start power plants worth crores.”

BMB also offers other kinds of credit, and women borrowers get lower interest rates. For example, 1% concession in interest rate is given to female students interested in education loans.

Challenges

Most women in India are unable to borrow money because they have no collateral to present to the bank. Traditionally, assets such as land or houses tend to be in husband’s or father’s name. To encourage more women entrepreneurs, BMB offers collateral-free loans for amounts up to Rs1 crore. (These borrowers have to take an insurance policy under the government’s Credit Guarantee Fund Trust Scheme and pay an annual premium)

Few countries such as Pakistan and Tanzania have set up state-run banks for women. So it is hard to predict the success rate of such an experiment.

Yet, the banks biggest challenge is reaching the poor, unbanked rural population. Even though BMB has branches in almost all of India’s states now—and aims to open a total of 80 by the end of this year—these are mostly located in large, urban cities.

“The first branch was inaugurated… in a very elite place in South Bombay and in a very elite building. I don’t think the objective of financial inclusion will be served by opening a branch in such an area,” said Charan Singh, a professor at Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, on the day the bank opened last year.

It will take years for the BMB to build a large network and be as well-known as some of the other established names in the industry. But to hasten the process, the bank offers small loans to rural customers though self-help groups and local NGOs.

“Village women save money in a jar in the kitchen. No matter how poor, the Indian woman knows how to save and she knows how to borrow, even though it is mostly from a moneylender,” said Ananthasubramanian.

Ananthasubramanian now wants to ensure that she borrows from BMB, instead of going to the local moneylender.