India treats its mentally disabled worse than animals

India cannot ignore the way it treats its citizens with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities anymore.

India cannot ignore the way it treats its citizens with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities anymore.

The Indian method of treating its mentally disabled is so flawed and cruel that those affected by it live a life “worse than animals” when left on their own or at mental institutions, says a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW).

A severe shortage of adequate mental health care professionals has made matters worse for the government as it readies itself to see almost 20% of its population troubled by mental illness by 2020.

On Wednesday, the New York-based advocacy group had said that those admitted to mental institutions in India are often subjected to physical and sexual violence and in some cases denied basic necessities such as a bathing soap, tooth brush or towel.

In certain cases, they are also forced to share a bathroom with 73 others or stay naked till their clothes come back from being washed.

“Women and girls with disabilities in India are forced into mental hospitals and institutions, where they face unsanitary conditions, risk physical and sexual violence, and experience involuntary treatment, including electroshock therapy,” the report says.

Manpower crunch

For the Indian government, the report should be an eye opener as it currently spends a paltry 0.06% of its GDP on mental (pdf) health care as compared to 0.44 % spent by Bangladesh and 6% spent by the United States.

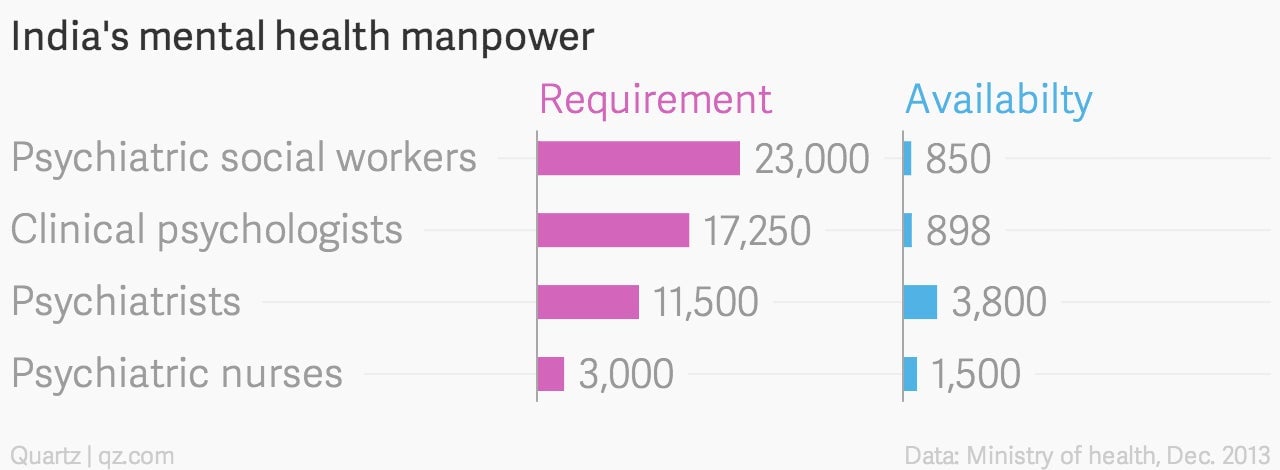

To further complicate the matter, there is a severe shortage of man power in the sector. The country demands more than 50,000 mental health professionals, but as of December last year, the available number of professionals stands at 7,048.

The Census of India 2011 estimates that 2.21% of the Indian population suffers from disability with 1.5 million people with intellectual disabilities and 722,826 people with psychosocial disabilities.

There are just 43 state-run medical institutions with three psychiatrists and 0.47 psychologists per million people in India. Rural India is worse affected by the crisis as 72% of the actual population lives there while only 25% of the mental health professionals are located in such areas.

In October, the government launched a National Mental Health policy (pdf) which will provide universal access to mental health care and upgrade mental hospitals in states at par with central institutions. The bill is waiting to be ratified by the parliament.