How India rescued its tiger population from the brink—but Modi is risking it all

First, the good news: Years of conservation efforts are finally making their impact felt, and India’s tiger population has grown by over 30% since the turn of the decade.

First, the good news: Years of conservation efforts are finally making their impact felt, and India’s tiger population has grown by over 30% since the turn of the decade.

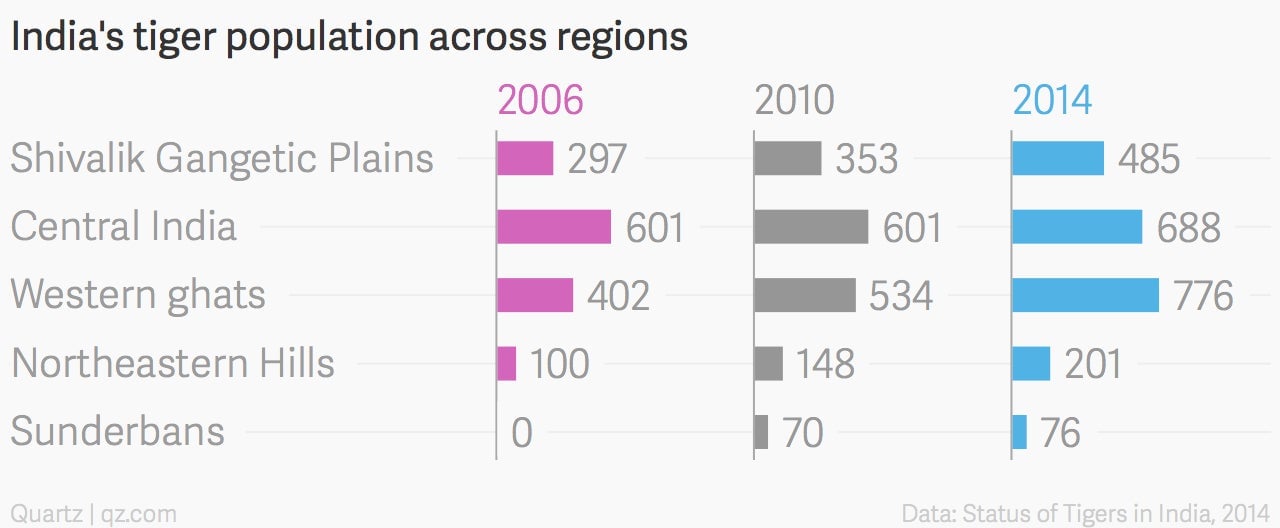

In 2006, there were just 1,411 tigers left in the country, and by 2010, the number rose to 1,706. The government’s most recent estimate, released on Jan. 20, suggests that there are now 2,226 tigers in India—about 70% of the world’s total population of 3,200 tigers.

Now, for the bad news: It’s not a situation that is likely to last very long, given the current government’s stance towards the environment.

“This increase in tiger population is a testimony of the success of various measures adopted by the government,” environment minister Prakash Javadekar said in statement. “These measures relate to Special Tiger Protection Force, Special Programme for Orphan Tiger cubs, efforts to control poaching and initiatives to minimise human-animal conflict and encroachment.”

But much of that happened when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance was in power. The incumbent Bharatiya Janata Party, on the other hand, has diluted environmental safeguards as it pushes for faster economic growth—and that has conservationists worried.

Counting stripes

The latest tiger census, India’s most extensive ever, covered 378,118 square kilometres of forests in 18 states, with camera traps at more than 9,000 locations and over 1,500 individual tiger photographs taken. In 2010, only about 72,000 sq km was surveyed and 550 tigers photographed (pdf) by camera traps.

But a bigger survey isn’t why the tiger numbers have suddenly spiked by 30% in just five years.

“We cannot take away the fact that the rise in numbers is due to better preservation and management and a strong political will,” Belinda Wright, executive director of Wildlife Protection Society of India, told Quartz. “But we have also covered more area this time and more cameras used for estimation.”

YV Jhala, one of the principal investigators of the tiger census, admitted that although the survey’s “precision and reliability has obviously improved,” the rising tiger numbers are a reflection of the improved situation on the ground. “I would not say that it is because of technology that we have increased numbers now,” he said in a telephone interview.

Not only have tiger populations inside tiger reserves been better protected in the last few years, explained environmental activist and writer Bittu Sehgal, but resettlement of villagers initially located inside reserves has also made a difference.

And while the previous government considered the advice given by conversationists and took corrective action, the Narendra Modi-led dispensation seems to be moving in the opposite direction.

“This government is reversing all those stands,” Sehgal said. “I can be almost 100% sure that it (current tiger population) won’t last.”

Growth vs conservation

In July this year, after the Modi government assumed power, one of the first steps it took was to reconstitute the National Wildlife Board. It is the apex body under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 that reviews all wildlife-related matters and approves projects in and around national parks and sanctuaries.

Before India’s Supreme Court held the decision unconstitutional, the newly constituted board had already approved 100 new projects that could have significant environmental impact. The environment ministry had also allowed projects to be set up within five km of a protected wildlife area without clearance from the board.

“The bigger challenge we have today is to ensure that we have enough corridors to ensure habitat connectivity and genetic breeding. That is the only way we can provide for further growth in tiger numbers,” said Jhala, “Infrastructure development has to happen, but we can compromise a little on our growth.”

“The challenge now is to balance conservation and economic growth,” he added.

“There is about 200,000 sq km of potential tiger habitat in the country. At the moment, tiger numbers are very low in states such as Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and (the) Northeastern states where widespread hunting of prey species has depressed tiger numbers,” said Ullas Karanth, senior director of Wildlife Conservation Society-India program.

These are also areas where the mining sector is looking to expand—and there are large industrial projects in the pipeline. Moreover, large infrastructure projects have now been exempted from seeking environmental clearances. All together, India’s environmental safeguards have rarely been any weaker.

“If attention is paid in future to having a goal oriented, time bound, cost-effective approach to tiger recovery, we can have four times more tigers in India, in the long run,” said Karanth.

But that needs political will—and the Modi government, by all indications, is more keen on promoting the “Make in India” campaign’s lion mascot than saving India’s tigers.