Is Narendra Modi the lifeguard who can rescue India’s ports and shipyards?

On May 16, 2014—the day Narendra Modi was elected as India’s new prime minister—Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone acquired Dhamra port, a joint venture between the Tata group and Larsen & Toubro, for Rs5,500 crore ($930 million) and stepped up its play on the east coast.

On May 16, 2014—the day Narendra Modi was elected as India’s new prime minister—Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone acquired Dhamra port, a joint venture between the Tata group and Larsen & Toubro, for Rs5,500 crore ($930 million) and stepped up its play on the east coast.

The company—controlled by India’s eighth richest man Gautam Adani—already operates India’s biggest private port on the west coast at Mundra in Gujarat.

Now, Adani is reportedly making plans to buy Essar Ports—India’s second biggest port operator—which will make it the biggest port operator in India after the union government.

Adani’s big play in ports also comes at a time when India’s port and shipyard sector is witnessing a renewed interest from Indian and global investors—and a lot of it has to do with prime minister Modi.

Weigh anchor

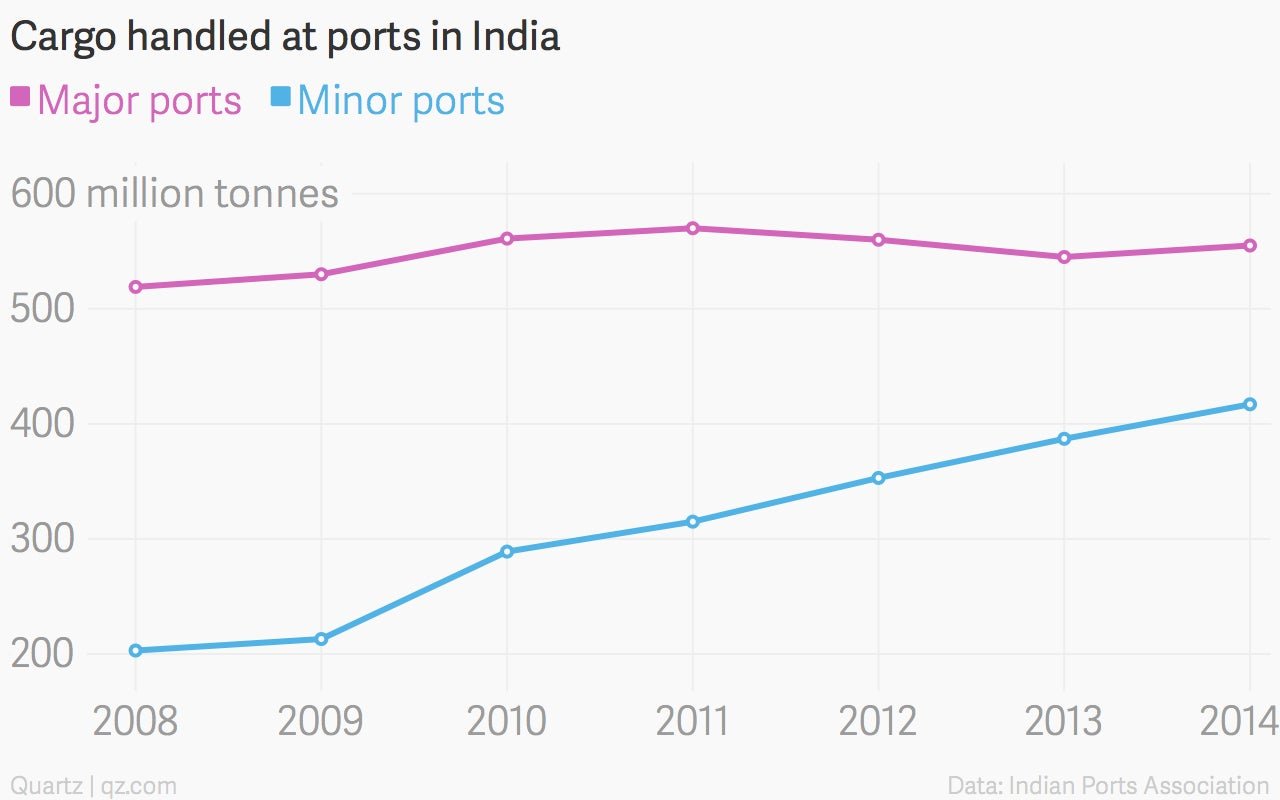

India has 13 major ports and 176 minor ports. The country differentiates its ports on the basis of jurisdiction—major ports come under the central government, while minor ports come under the state government.

Almost 90% of India’s foreign trade goes through sea ports, of which nearly 57% is handled at major ports.

But since the turn of the century, India’s major ports have lost out as much as 20% of their total cargo to minor ports due to inadequate capacity and longer turnaround time—the time taken to unload and reload freight. It hasn’t helped that the number of minor ports has steadily grown in the last decade and a half.

And as the Modi government seeks to push manufacturing and revive India’s power and coal sectors, the country’s minor ports are coming back into focus.

“There will be further consolidation in India’s port sector, largely because everybody is anticipating the government to help the port sector in a big way. As India’s coal and power projects are also expected to kickstart, ports will be buzzing with activity,” Anand Sharma, director at Mumbai’s Mantrana Maritime advisory, told Quartz.

Sharma believes that it will be worthwhile for companies to buy ports at lower valuations now, since the rewards are expected to be better in the long term.

And many are banking on Modi’s stellar history of transforming the maritime sector in Gujarat, as the western Indian. Last fiscal, cargo traffic at non-major ports in Gujarat grew by 8%—and accounts for more than 70% of the total cargo handled by non-major ports in India.

“As this government looks to boost manufacturing and exports, it will be the ports that will play a crucial role. And the new government is actively studying all the issues in the sector and many of the regulatory concerns will become a thing of the past,” said Vishwas Udgirkar, partner at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

Deep problems

Except Chennai’s Ennore Port, which is operated as a company, the remaining 12 major ports in the country function as government-owned trusts. But the Modi government, in its first full budget last month, said that it intends to corporatise these establishments.

That’ll mean India’s major ports will have more autonomy and control over their operations, unlike the current situation where ports have to seek permission from the government for any policy-related issue.

For decades, India’s ports have suffered from chronic under-investment and a lack of strategic planning, including inadequate linkages to railway and road transport networks. The result is that for key parameters like turnaround time, Indian ports have an average of 84 hours. Ports like Singapore and Hong Kong need just seven hours.

In 1996, with an eye on improving the dire situation, the Indian government opened up the ports sector to 100% foreign direct investment and global operators such as APM Terminals and DP World have already established presence in the country. While APM Terminals operates a port in Gujarat, DP World owns a number of terminals at major ports in the country.

But India’s private port companies have their own problems. Essar Ports, for example, was saddled with about Rs5,836 crore ($950 million) at the start of this fiscal. Another minor port, Krishnapatnam port was grappling with a debt of around Rs 3890 ($600 million) crore in 2013.

“A lot of companies are troubled by debt and we will see the big players buying out the smaller ones since they have high debt and as India’s economy looks to grow, ports will bring in good business,” Ramesh Singhal, chief executive of I-Maritime, a Mumbai-based consultancy service, said.

War footing

India’s first modern shipyard was built in 1941. But a little over a decade later, in 1952, the government of India took over Vizag’s Scindia shipyard and renamed it Hindustan Shipyard. And the government has effectively dominated India’s shipbuilding industry since.

But that could change soon.

In particular, prime minister Modi’s big push for domestic manufacturing in the the defence sector just woke up a long slumbering industry. Immediately after assuming power, the Modi government also raised foreign direct investment in defence sector to 49%, allowing international firms to set up joint ventures with Indian companies to build defence equipments.

On March 5, Pipavav Defence and Offshore was bought over by Anil Ambani’s Reliance group for Rs2,082 crore. But at least three other companies including India’s Mahindra group, Hero Group and France based-DCNS were in the race to purchase stake in the company, which had earlier bagged a few key navy projects to build vessels.

On March 9, the Indian government shortlisted Pipavav Defence and Larsen & Toubro to build six submarines for the Indian government worth Rs60,000 crore ($10 billion) along with public sector shipyards.

ABG shipyard, India’s largest private shipyard, is also in the market looking for suitors, and companies including Mahindra and Adani have shown interest in buying a stake in the company.

“Defence is a game changer for ship builders in India,” Dhananjay Datar, the shipyard’s executive director and chief financial officer, said in a television interview. “And that will attract a lot of players as government has allowed FDI up to 49%.”

In 2013, India had spent Rs1,863 crore ($300 million) on acquiring equipment for the navy—and is one of the world’s largest arms importers, buying over $5 billion worth of military hardware in 2015.

But with an estimated $130 billion (Rs8.2 lakh crore) likely to be spent on upgrading the country’s defence forces by 2022, the Modi government wants domestic firms to grab a slice of this massive outlay—including for the navy.

“On the shipyard front, there will be some big acquisitions,” I-Maritime’s Singhal said. “New entrants are coming in looking at the prospects of the defence sector, which has been opened up to the private sector. But in the short term, it will still be the public sector shipyards, which will partner the government in defence production.”