Bihar’s cheating fiasco was shameful—but stop mocking those parents because it’s not their fault

Justifying an act of cheating could appear to be a moral low point—but in Bihar’s case, it needs to be done.

Justifying an act of cheating could appear to be a moral low point—but in Bihar’s case, it needs to be done.

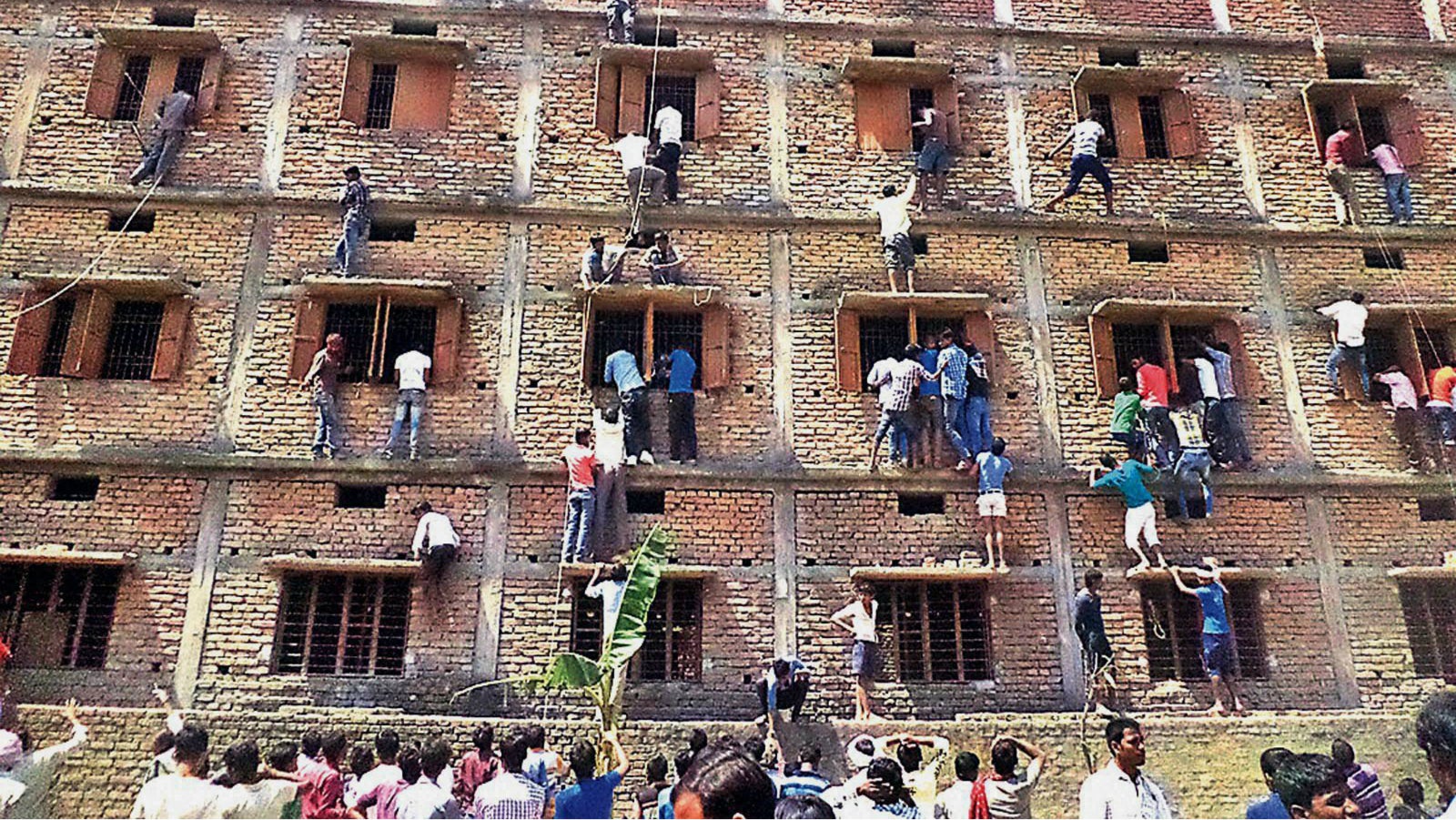

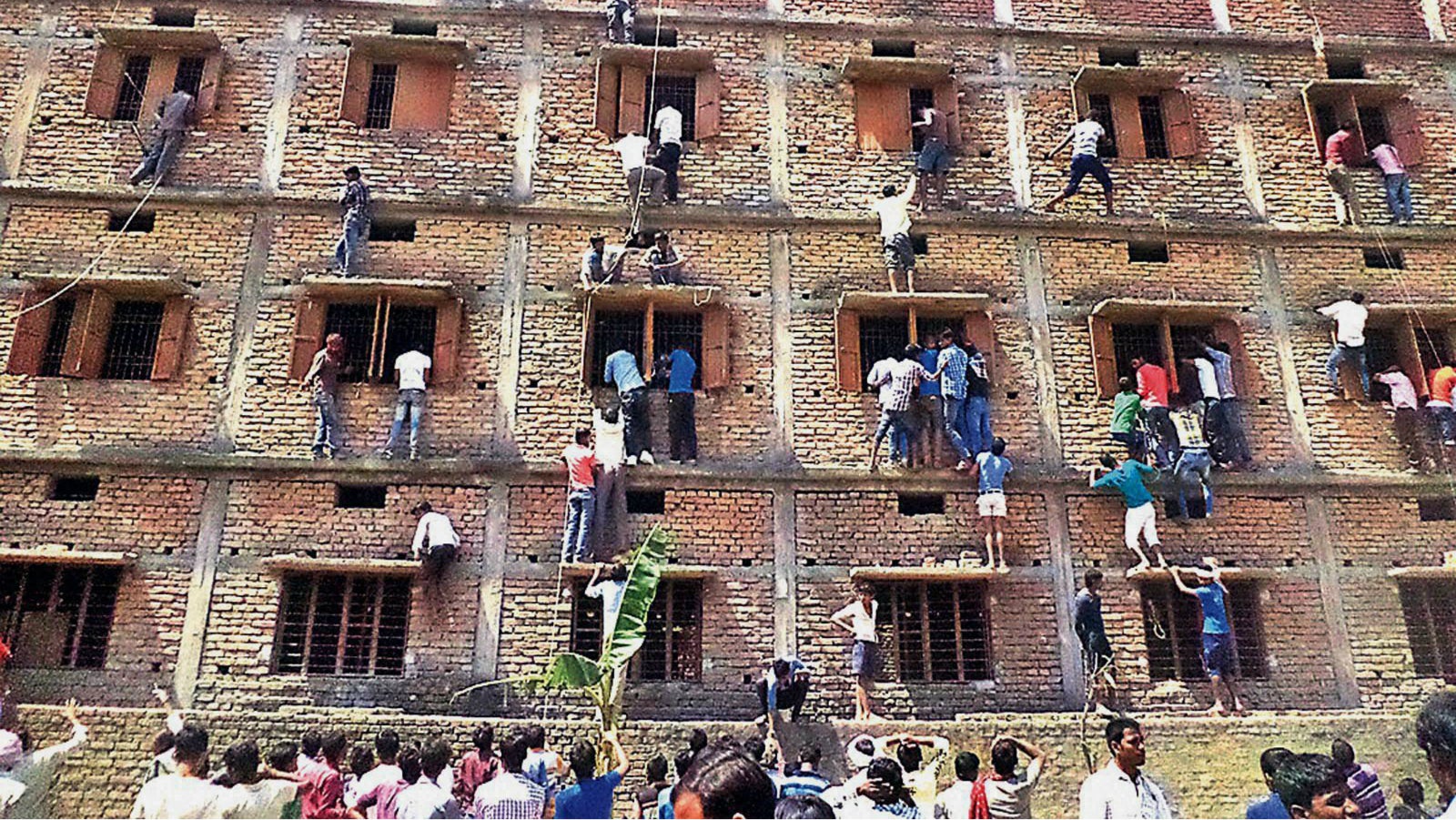

For a few days now, a bizarre photograph of people climbing an unplastered brick wall of a four-storey building has stoked curiosity, mockery, outrage and shame. After all, how could parents and relatives of students appearing for the state board’s class 10 examination so brazenly aid their wards in this illegal exercise?

But what transpired at Vidya Niketan School in Mahnar, a town in Bihar’s Vaishali district, isn’t a solitary incident in the state.

“It seems I have seen this photograph way too many times… because it happens every year,” said Piyush Kumar, a former government school student from Kawakol, a nondescript town in Bihar’s Nawada district.

Kumar—now a 24-year-old student at the University of Delhi and theatre artist—began his education at a private school, which only had classes up to grade 6, and then switched to a government-run institution.

In many ways, the education system that Kumar suffered through is exactly what millions of Bihar’s school children must deal with. It is dangerously ill-equipped and massively mismanaged, a rather disastrous state of affairs in a country where half the population is under the age of 25 years.

And that is why, perhaps, parents and guardians of countless children in Bihar do everything that they can—including scaling buildings and passing cheat sheets—to help these students succeed in the face of a broken education system.

Flooded schools, absent teachers

“In my school, if it rained, you got to run home, because the ceiling might fall down, or the school might be flooded,” Kumar told Quartz. If it rained incessantly for a few days, he added, the principal would simply declare a holiday.

Countless children in Bihar have to study in schools like these. In 2014, the enrolment in government schools—which are funded and run by the state administration—in Bihar was 81.8%. Only 11.2% went to better equipped, but more expensive, private schools.

During his high school years, Kumar often did not have teachers in the classroom. So, in grades 9 and 10, the principal of Kumar’s school urged every child to contribute Rs10 ($0.16) monthly—over and above the tuition fee—to help the school arrange a math and science teacher.

In 2013, a report found that the average student-teacher ratio in the state is 57:1, though the Right to Education Act mandates a 30:1 ratio at primary schools, and 35:1 in upper primary. Across Bihar, the average number of students in each classroom was 82.

The state specifically has a massive shortfall of primary and upper primary teachers—114,609 primary-level and 82,303 upper primary-level posts for teachers were found vacant in 2014. For upper primary, the shortfall is the worst in India, while for primary, it is the second worst after Uttar Pradesh.

When the government tried to fix the problem, the results were terrible. Between 2006 and 2012, a bevy of teachers was hired under what came to be known as the state government’s ”degree lao, naukri pao” (bring your degree, get a job) initiative. But many of these teachers had fake degrees.

When students have such a weak start, most are likely to keep struggling through the rest of the school.

The impact is evident in their learning capabilities: About 50% of Bihar’s government schoolchildren in grade 1 cannot recognise numbers one to nine. Among grade 4 students, 60% cannot solve math problems involving subtraction, and more than 50% cannot read words. And among grade 5 students, more than two-thirds cannot solve math problems involving division, and 70% cannot recognise and read words. Only a dismal 16% students can read a full sentence.

Another manifestation of grossly inadequate infrastructure and missing teachers is that students just don’t turn up at school. In 2014, only 71% of enrolled children attend schools in rural India. In Bihar’s case, between 50% and 59% students actually showed up.

“There were students who would fall behind because with studies, they worked on the fields or grazed cattle,” Kumar remembered.

So, after dealing with all this, when it comes to facing examinations and moving to the next grade, not every student is exactly equipped for the test.

“There were the influential students of influential parents—they could have a connection with the teacher, or with the sarpanch (head of the village who acts as a mediator between the government and villagers)—and they would tell the examiner: ‘This is the roll number. This is the seat. Thoda dekh lena,'” explained Kumar.

Basically, “thoda dekh lena”—or “look after a little” in Hindi—is local parlance for “help the kid cheat” during the examination.

Setting the wrong example

In all likelihood, that is exactly what played out at Vidya Niketan School in Mahnar earlier this month.

After the photograph went viral, the school building is now being guarded. The security is tight. And journalists are being chased away to steer clear of any more controversies.

Reacting swiftly to the widespread criticism, the Bihar government cancelled exams at four centres. Eight cops were also taken under custody for abetting cheating, even as roughly 750 students were expelled.

But politicians in Bihar haven’t always been ardent supporters of educational standards in the state.

This is what former chief minister Lalu Prasad Yadav had to say after the photograph surfaced: “Had it been my government we would have given books to examinees to write … only those who have read could write answers from books, and for those who have not exam duration of three hours would end and they would still be searching for answers.”

Once out of Bihar’s government schools, these students—cheaters, or otherwise—must then compete with counterparts from well-run, well-equipped and well-staffed institutions from across the country for college seats and eventually jobs.

And it’s not always easy—or particularly fair—as Jitendra Kumar, a student of Jawaharlal Nehru University who is from Bihar, recently wrote in a blog post on India Resists:

There might be several students who are not necessarily dumb but only higher marks can make them eligible to get their admissions in colleges or sit in competitive exams. Once they are out applying for their admissions, they have to compete equally with others coming from different schools, different background and different boards. This ‘different’ stands for privileged…If I were one among those parents, I too would have climbed up to the top floor too for a better future for my child.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].