Depression kills too many people in India but smartphones can help

India has among the highest rates of depression in the world. If Deepika Padukone, a leading Bollywood actress, hadn’t talked publicly about her battle with depression, you probably wouldn’t know.

India has among the highest rates of depression in the world. If Deepika Padukone, a leading Bollywood actress, hadn’t talked publicly about her battle with depression, you probably wouldn’t know.

And the stigma attached to mental illnesses is hurting India. Few are brave to speak about it to someone and fewer still get treated. The result is that, for every 100,000 Indians between 15 and 29 years old, 36 commit suicide annually—the highest rate among the youth in the world.

Worse still, according to Vikram Patel, professor of mental health at the London School of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine and one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2015, without urgent improvement in treating mental disorders, suicides will soon become the leading cause of death among the young.

Show me the money

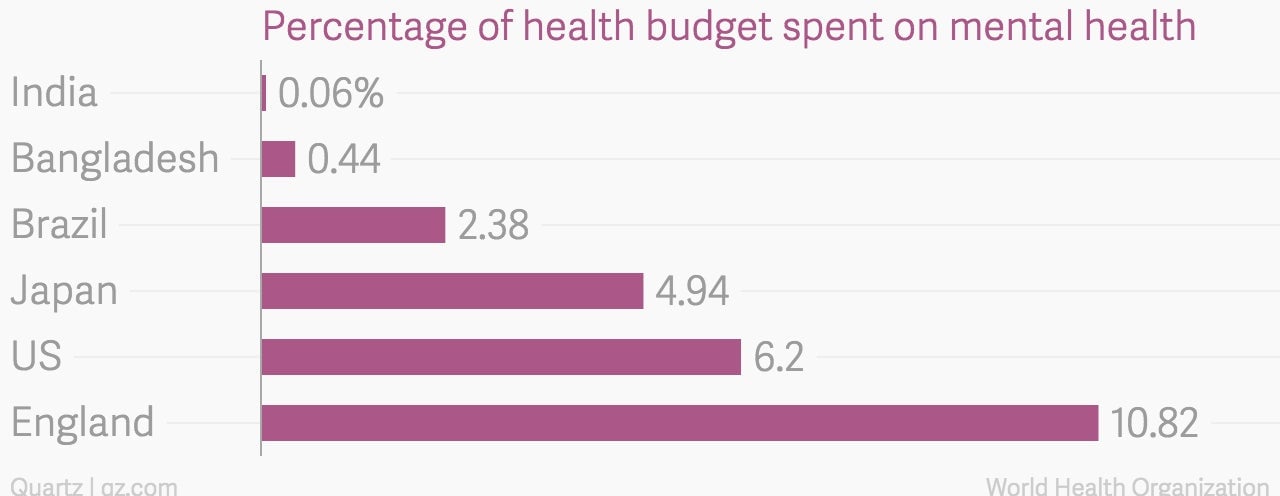

The Indian government has, thankfully, woken up to the problem. In October 2014, it released a mental health policy with a call to increase spending. Currently, according to the World Health Organisation, India spends a paltry 0.06% of its already small health budget.

With only one psychiatrist for more than 300,000 Indians—by comparison, England has as many as 59 psychiatrists for a similar population—and fewer psychologists still, there are huge holes to fill before we can start seeing results. But leaders in the field argue that mere increase in funding won’t help. What needs to change is the approach to solving an urgent problem.

India needs to invest in building the infrastructure—more doctors, more hospitals—that can be used to treat mental illnesses. But such development, especially when it involves increase in skilled human resource, has a long lead time before effects can be seen.

There, however, may be a quicker alternative to get results. The George Institute for Global Health has come up with an idea that they believe will immediately improve primary mental healthcare in rural India.

Rural first

Launched in January 2014, the smartphone-reliant approach is aptly named SMART—Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment. The scheme operates in about 40 villages in the state of Andhra Pradesh, and brings mental health services to the doorstep.

Piloting the scheme in rural India makes sense for two reasons. First, the scheme is modelled after a successful experiment that helped manage common cardiovascular diseases in rural and remote Australia, which makes it easier to replicate in India. Second, suicide rates in rural areas may be higher than rest of the county.

The scheme takes a practical approach. Villagers, usually women, educated to grade 8 or higher, are trained as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) according to a scheme launched by the government’s National Rural Health Mission. They are then equipped with smartphones or tablets, which they use to conduct standardised tests.

Remote doctors look at the data uploaded by ASHAs and perform preliminary analysis. If the diagnosis is of a common and easy-to-treat mental illness, instructions are sent back to the ASHA nearest to the patient. The ASHA can then monitor whether the patient chooses to accept the information or not. Serious diagnoses are referred to a visiting physician.

In all this, ASHAs get compensated for their work, ensuring that primary care remains free for the villagers. Alongside the standardised tests, ASHAs also work to increase awareness of mental illness through group activities and marketing pamphlets.

There are limitations. The project reaches about 120,000 now, but it is not clear if it can be scaled up without better infrastructure and more doctors. The primary care doctors in villages are heavily burdened, attending up to 300 patients a day.

Still there is hope. ASHAs have been trained and deployed with technology to work on other health indicators too. For instance, in Punjab, ASHAs armed with tablets and special diagnostic devices have been saving lives of pregnant women. A community-based approach may bring quicker results, while the country waits for bigger investments in improving mental health.

This article was also published in Lokmat Times. Please send your comments to [email protected].