Modi’s math is wrong: Only 8% of projects are actually held up because of land acquisition

This post has been updated with a new chart.

This post has been updated with a new chart.

On April 28, Reliance Power announced it would abandon plans to build a Rs36,000 crore ($5.6 billion) power plant in Jharkhand. It was taking too long, the company said, to obtain land for the project’s infrastructure.

That is precisely what the Narendra Modi government has argued for the past few months: India’s stringent land laws are costing the economy billions of dollars in potential investment like the Reliance Power deal, as big projects like dams and factories get mired in a tedious land acquisition process.

And this argument is the justification behind a controversial amendment to India’s Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act that would allow companies to acquire large parcels of land for certain categories of projects without the consent of the landowners.

“A larger public interest always prevails over private interest,” Arun Jaitley, the finance minister, wrote in a Facebook post. “A highly complicated process of acquisition which renders it difficult or almost impossible to acquire land can hurt India’s development.”

And in a recent conversation with the Indian Express newspaper, India’s transport minister Nitin Gadkari argued that “if the consent clause remains, no work can happen.”

But the government’s own figures appear to contradict the narrative that land acquisition is crippling India’s economic growth.

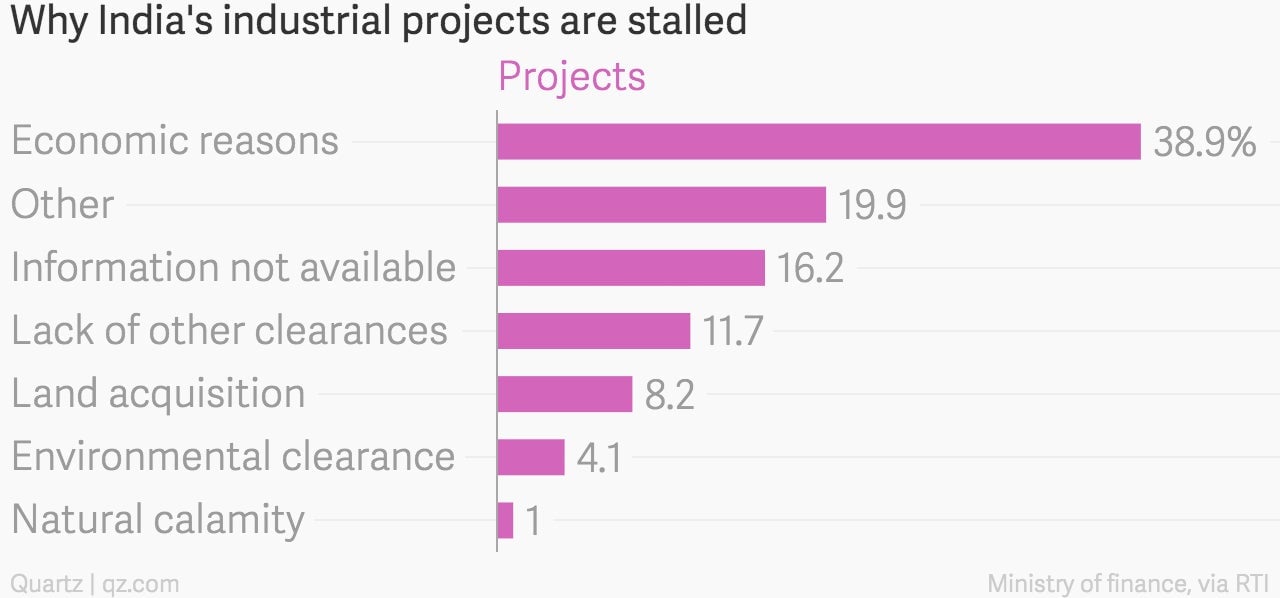

Out of the 804 major ventures that have been brought to a standstill across the country, only 8% face problems with acquiring land, according to data obtained from the finance ministry by Right to Information activist, Venkatesh Nayak.

Meanwhile, nearly 40% of stalled projects—which range from power plants to shopping malls and luxury housing—are held up for economic reasons like fuel supply shortage or lack of investor interest. And while 16% are waiting on various forms of regulatory approval, only a small handful are stalled by environmental clearances—another grouse of the Modi administration.

The prime minister seeks to change a previous land acquisition law that came into force last year, which requires most projects to obtain the consent of at least 70% of the landowners they would displace. Modi has already issued an ordinance in December that, among other important changes, exempts all investments in defence, rural infrastructure, affordable housing, industrial corridors and government partnerships from obtaining any consent. (Since it’s so recent, the ordinance is unlikely to be the reason why so few stalled projects face land issues.) And if his amendment to the act passes through both houses of parliament, those changes will become law.

Economic factors, not stubborn farmers

Critics say the proposed legislation unfairly privileges private corporations over the rights of small farmers.

“Growth has taken over the agenda in extremely illiberal ways,” said Preeti Sampat, a public policy scholar at the Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy. “There is this understanding that what we need is more investment in large projects like infrastructure, so the only way forward in terms of growth is for people to get out of the way of these big projects.”

Yet Modi’s own finance ministry has acknowledged that economic factors—and not stubborn farmers—were holding up most of the Rs7 lakh crore ($110 billion) worth of stalled private sector ventures across India.

“It is clear that private projects are held up overwhelmingly due to market conditions and non-regulatory factors,” noted the ministry’s annual economic survey. “Perhaps contrary to popular belief, the evidence points towards over exuberance and a credit bubble as primary reasons (rather than lack of regulatory clearances) for stalled projects in the private sector.”

That means that the huge glut of projects abandoned by the private sector was probably caused by a faltering investment boom instead of red tape. The survey did note that policy paralysis was more likely to thwart government projects like roads and hydroelectric dams—but these accounted for a much smaller Rs1.8 lakh crore ($28 billion) in stalled projects.

Economists cautioned that just because only 8% of currently stalled projects faced land acquisition problems doesn’t mean all big-ticket projects are likely to have it so easy.

“It’s a classic underreporting problem,” said Maitreesh Ghatak, a professor at the London School of Economics who has studied land acquisition law in India. “There may be projects that never got started because they anticipated these problems. Also, the ones that did get started are likely to have been selected because the risk of land acquisition problems was low for them for whatever reason.”

And any successful land acquisition law in India will need to let farmers name their own price, said Parikshit Ghosh, a professor at the Delhi School of Economics. “The real problem is that all iterations contain this very serious problem that price of the land is not determined in a participatory or rational way,” he told Quartz, pointing out that even the previous laws established arbitrary values for land. “So until the people participate in negotiations themselves, and say that this is the price that we’re happy with, land acquisition is going to keep being an issue.”

Modi’s tough stance on land acquisition is shaping into the biggest showdown of his administration so far. The bill has sparked nationwide protests by thousands of farmers who fear forcibly losing their land, including one man’s suicide at a recent rally in Delhi. Opposition parties like Congress and the Aam Aadmi Party have been quick to capitalise on the anger, staging rallies and calling the government a “suit-boot ki sarkar.” Even the Bharatiya Janata Party allies have distanced themselves from the legislation for fear of appearing anti-farmer.

For his part, Modi has dismissed the opposition’s remarks as a “conspiracy” to thwart the development of both farmers and the country. But he will soon require a better argument than that.