Why India’s met department could be wrong about its monsoon forecast

On June 02, India’s met department had some terrible news to share with a sweltering country: The monsoon rains may be deficient (pdf)—and Asia’s third largest economy could be staring at a drought year.

On June 02, India’s met department had some terrible news to share with a sweltering country: The monsoon rains may be deficient (pdf)—and Asia’s third largest economy could be staring at a drought year.

But the 140-year-old Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) could be wrong.

Or, at least, that’s what Skymet—India’s largest private weather forecaster—contends, just as it did with its April 22 forecast that the monsoon will be 102% of the 50-year-long period average (LPA). In other words, the monsoons, which account for about 70% total rainfall in the country, will be normal.

The LPA is the average rainfall that the country received between 1951 and 2000 during the monsoon season that extends from June to September. The average is benchmarked at 89 centimetres of rainfall.

“We stand by our prediction,” Mahesh Palawat, chief meteorologist at Skymet, told Quartz. “Even in the worst-case scenario, we believe that monsoons will be 98% of the normal. That would still mean normal rains this year.” With a network of 2,500 weather stations and a team of 10 climatologists and meteorologists, Skymet has—for the past three years, at least—been more accurate than the IMD in forecasting the monsoons.

The IMD, on the other hand, now reckons the monsoon will be less than 90% of the LPA. On April 22, its rainfall prediction for the season was at 93%.

If the IMD’s predictions are accurate, then 2015 will be the second straight year that the country will deal with deficient rains, a massive challenge for prime minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious plans to revive India’s subdued economy.

Much of this grim forecasting is because of the El Nino, the warming of the sea surface in the Pacific Ocean, which leads to lower rainfall in Asian countries. The IMD and Skymet both believe that the chances of El Nino suppressing the monsoons is 90%.

“But there is another huge factor that could counter the El Nino’s effect,” Palawat said.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), also known as the Indian Nino—caused by the difference in sea surface temperature between parts of the western and eastern Indian Ocean—is expected to remain positive.

A positive IOD would mean greater chances of rainfall in the Indian subcontinent and counters the El Nino effect. In 1997, for instance, an El Nino effect that threatened to disrupt India’s monsoons was countered by a positive IOD.

“The temperature in the Arabian Sea has been above the normal so far and we think that this can cause a positive IOD. That would balance the El Nino effect and in turn bring good rain fall.” Palawat said.

The IMD, however, believes that there’s “about 50% probability of neutral IOD conditions to continue during the monsoon season.”

Skymet is also convinced that the chances of a back-to-back drought season are slim, given that India suffered a mild drought last year. ”In the last century, back-to-back droughts have happened only three times,” Jatin Singh, CEO of Skymet, told Quartz. ”Once in the 1904-05, 1966-67 and in 1985-86-87.”

“So, the chances of a back to back drought is only 3% and we believe that it won’t occur this year. We also relied upon our modelling techniques to come to that conclusion,” he added.

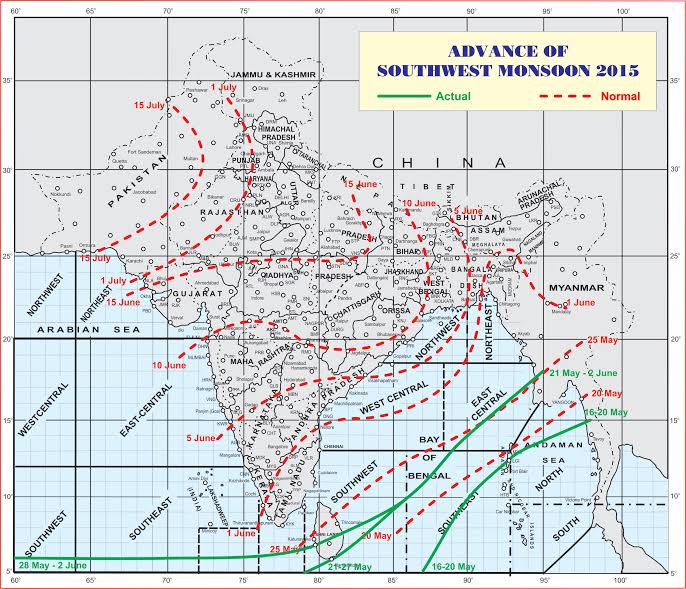

India’s monsoon rains are now finally expected to hit the southern state of Kerala on June 05, five days after it was expected to make landfall. By September, it’ll be clear who was right.