I grew up as an Indian expat in Iran, before the revolution

Before the Iran deal, most Indians didn’t give Iran a thought. For the last 35 years, neither have I, for the most part. Like many of us, I glanced occasionally at photos of ranting ayatollahs and grim faced women in black, shuddered, and move on.

Before the Iran deal, most Indians didn’t give Iran a thought. For the last 35 years, neither have I, for the most part. Like many of us, I glanced occasionally at photos of ranting ayatollahs and grim faced women in black, shuddered, and move on.

But it wasn’t always like this. That winter of 1975, when I moved to Iran with my parents and sister, India and Iran didn’t seem so far apart.

Our move happened because of Indira Gandhi’s 1974 visit to Iran. Iran agreed to sell oil to India cheaply, in a sweetheart deal. In return, Indira agreed to send doctors and engineers to train the Iranians. My father, a pediatrician with a massive love of adventure and a correspondingly tiny bank balance decided to go.

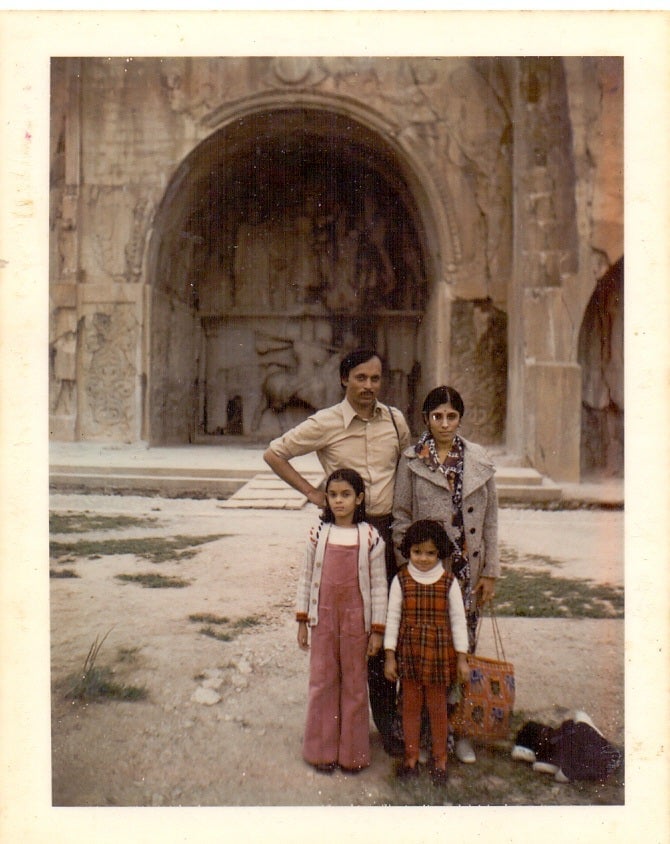

We began our Iranian adventure in the remote town of Kermanshah, part of Kurdish territory, famous for its bas-reliefs from the time of ancient Persian king Darius. But in that cold winter, we had little time to sightsee. We arrived to a fierce, unprecedented snowstorm, and a house with a collapsed roof. My mother, with two children under five, had to immediately run a household on a tiny budget. Meanwhile, my father had to quickly learn both Farsi and Kurdish, treating mostly poor tribal children in a free government hospital.

My first real memory, at the age of four, is of being very cold, watching the snow, falling mercilessly outside our window. There was no central heating, only an old kerosene heater for the entire house. It was snowing too hard to go out, and we had no car, so my sister read to me for hours, building a passion for reading that remains with me.

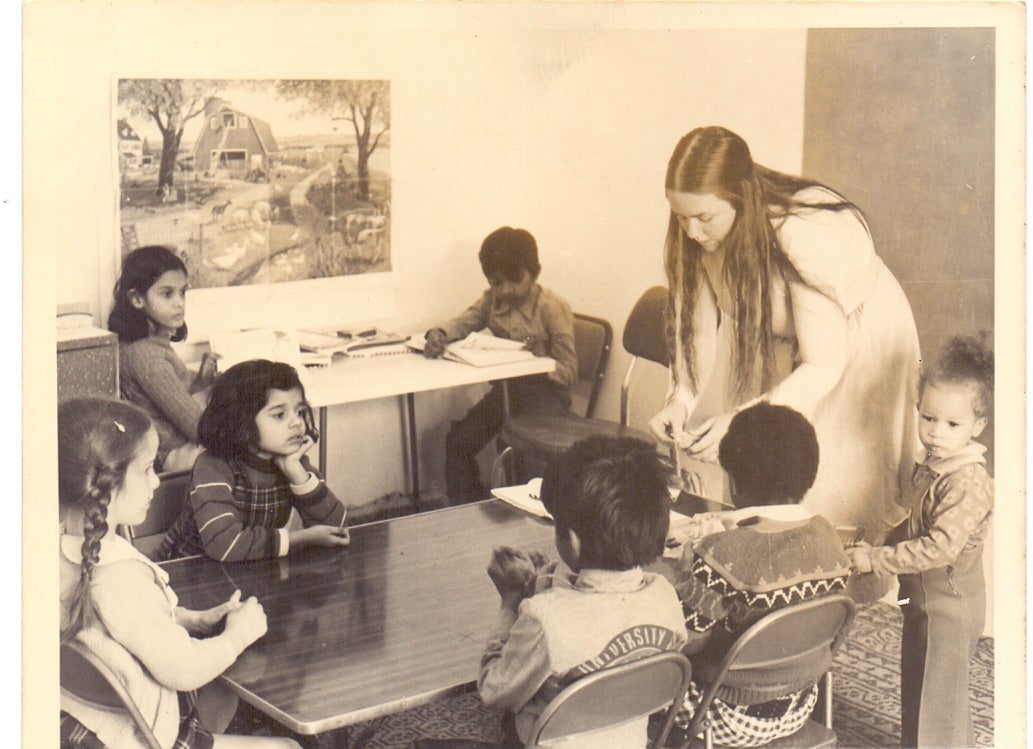

There was no suitable English school, so we were home-schooled for the first year. Then we found an American teacher from Baltimore, who set up a tiny school of five children. My sister and I formed half the student body. We had few English books, and read our single copy of C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe so many times that years later, I can still recite it by heart.

For entertainment, we watched American television dubbed in Farsi. I learnt my first alphabet from watching Sesame Street. Later, I was enraptured by the kick-ass escapades of the Charlie’s Angels heroines. America back then, while not exactly popular, was not the great Satan that Khomeini would later call it.

There were American teachers, engineers, missionaries in our town, even some Jewish ones. We listened to the haunting, husky voice of the stunning Googoosh, a popular Iranian pop singer. I remember eating fresh, still warm naan with everything, even sambar, and gorging on cherries, melons and watermelons, as my mother grappled with managing our strictly vegetarian household.

In those days, Iranian women were the epitome of chic. The most conservative would wear a chador ( headscarf) loosely tossed over their heads. The most modern—usually in Tehran—would go as far as short skirts, bellbottoms and bare shoulders. There were plenty in between, wearing trousers or long dresses. My mother, unused to wearing anything but a sari, wrapped her flimsy georgettes tightly around her midriff, and moved around with no trouble, though somewhat self-consciously.

“I felt so unfashionable next to the Iranian women with their lipstick, high heels, and French perfume,” she recalls.

After a couple of years, we moved to Zahedan, the desolate capital of the Baluchistan province, 40 km (25 miles) from the Pakistani border. My sister and I went to a school started by Sikh soldiers, who had come to Iran as part of the British army in the 1940s. Their descendants were everywhere, running Indian stores or working as construction workers.

Just like every Indian office or school has a picture of Gandhi, every Iranian one had a picture of the emperor, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. To our childish eyes, the Shah was marvellous, perched on his golden Naderi throne, his glittering Pahlavi crown almost too brilliant to look at, smothered with what I later discovered were 3,380 diamonds, not to mention egg-sized emeralds.

Blissfully ignorant of politics and the royal family’s increasingly corrupt ways, we also gaped at the stunning Empress Farah’s jewels and evening gowns. We hankered after her mini-skirts, her sixties-inspired eyeliner, her little pillbox hats, à la Jackie Onassis.

And then suddenly, it all came to an end. In 1978, we began to hear rumors of unrest in Tehran. There was increasing public resentment of the Shah’s extravagance, and his closeness to America. We were so far away in rural Zahedan that it took us some time to realize that Iran as we knew it was collapsing. In August 1978, the Cinema Rex theatre in Abadan was destroyed by unknown arsonists, killing hundreds. The Shah was blamed, and this was the trigger of revolution.

Before we knew it, all flights from Tehran were cancelled. There was no way, it seemed, to get out of Iran. A friend of my father pulled strings, and got us out on the last plane out, a Pakistan Airlines flight, with a layover in Karachi. Pakistan’s authoritarian president, Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, was in power, and we worried Indians might not be allowed in the country. It was not a flight we would have chosen, but eventually it got us back home.

But my father had not finished his contract, or received his wages. He went back to serve out his contract. By this time Ayatollah Khomeini was in power. “Everything had changed,” he recalled. “The streets were filled with young boys, only 15 or 16, toting machine guns. There were no women anywhere. One young boy, brandishing a Kalashnikov, came up to me and asked me what I thought of the change of guard. I don’t think anyone, even Khomeini, had ever been so enthusiastic about the revolution, as I was that day.”

My father boarded a flight to Zahedan, where he shouted “Marg bar Âmrikâ. (Death to America!)” with his former patients. He returned only a few months before the American embassy was taken hostage by revolutionaries, in 1979.

Iran seemed like a dream as we settled back into an Indian school. The Iran of our times faded rapidly. Googoosh stopped giving public performances, after women were banned from singing solo in public. The Shah died in exile in 1980, and his family was dogged by tragedy, two of his children committing suicide. The Indian population in Zahedan dwindled, as many Sikhs decided to move elsewhere.

But until my father’s death, he remembered his Iranian days as amongst the most satisfying of his life, helping the children of the poorest of the poor, nomadic Kurds, immigrant Pakistanis, Sikh laborers. In times to come, making ten times more money, in state-of- the-art hospitals, he would remember those days wistfully.

“They listened to me, followed my instructions far better than their highly educated counterparts,” my father would say.

“I was proud to be the wife of a doctor. We were so respected everywhere we went,” says my mother.

It’s probably naïve to think, so many years after the revolution, and with such a yawning gap in ideology, that India and Iran can ever be close again. Perhaps we shouldn’t be. But in these days of the Iran deal, of collapsing Berlin walls, of the first black American president, of unpredictable political changes, I can’t help but hope it might happen.