Should India join the Trans-Pacific Partnership?

The US and 11 other countries have concluded negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade pact that will cover 40% of global trade spanning Asia and the Pacific Rim, including some Latin American countries. It represents a subset of the countries in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, and one can anticipate that other APEC members may elect to join the TPP in the future. While China, the largest economy in Asia, has not been part of the negotiations, it has “welcomed” the agreement. The Japanese prime minister has indicated that Chinese membership in the TPP would aid “Asia-Pacific regional stability.” Back in June, US president Barack Obama said that Chinese officials had been “putting out feelers” about joining.

The US and 11 other countries have concluded negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade pact that will cover 40% of global trade spanning Asia and the Pacific Rim, including some Latin American countries. It represents a subset of the countries in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, and one can anticipate that other APEC members may elect to join the TPP in the future. While China, the largest economy in Asia, has not been part of the negotiations, it has “welcomed” the agreement. The Japanese prime minister has indicated that Chinese membership in the TPP would aid “Asia-Pacific regional stability.” Back in June, US president Barack Obama said that Chinese officials had been “putting out feelers” about joining.

So where is India? India has not yet indicated whether it has interest in pursuing the TPP membership down the line. This is because no clear consensus has formed in India on whether expanded market access will help the Indian economy grow, and whether the gains will be worth the potential costs to some still-protected Indian industries. To think about a possible TPP membership, India would have to prepare itself for more significant market opening as well as enhanced standards than it has committed to in the past. Indian officials will need to decide whether they wish to position their country for the increased trade flows that participation in a major regional agreement would provide.

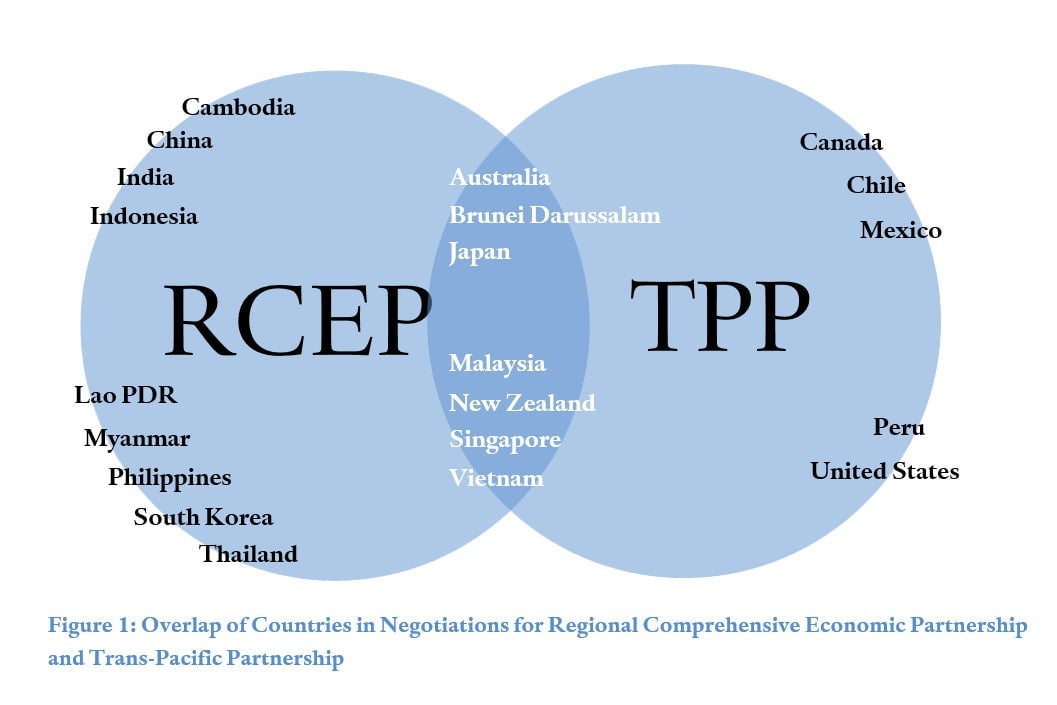

Of course, a negotiation separate from the TPP has been underway in Asia: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). India and China participate in this negotiation centered around the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Seven countries—Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam—are participating both in the TPP negotiations as well as in the RCEP. Trade experts generally assess the RCEP process as less demanding than the TPP.

In addition, within Asia, major economies like China, Japan, and India, as well as emerging economies have been pursuing bilateral and regional trade negotiations among themselves. China and India have negotiated free trade agreements (FTAs) with ASEAN to advance their own, and ASEAN’s, interests. Both have separate bilateral agreements with Singapore. Looking across the Pacific, China has FTAs with Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru. India has been negotiating an FTA with the European Union for nearly nine years, completed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Japan in 2011, and is in the process of negotiating CEPAs with Australia and with Canada.

In a study released in September, C. Fred Bergsten of the Peterson Institute for International Economics argued that India could gain as much as $500 billion in exports by joining an expanded TPP. For a government interested in boosting the country’s exports and creating jobs at home, that certainly sounds like compelling logic. India has become more vocal internationally about its unambiguous interest in joining APEC, a necessary stepping stone for the TPP membership, but here it appears New Delhi has some further work to do to convince its partners, including the United States, that it is ready.

While the US-India Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia Pacific and Indian Ocean Region released in Jan. 2015, welcomed India’s “interest in joining” APEC, no follow-up statement from the US emerged from the September meeting between Obama and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, nor did any of the numerous documents released following the first US-India Strategic and Commercial Dialogue include it. In his joint press conference with Obama following their Sept. 28, 2015 meeting in New York, Modi said he looked “forward to work with the US for India’s membership of Asian Pacific Economic Community.” Modi’s statement had no echo from Obama.

I’ve argued elsewhere that it is in the US’ interest to develop a more ambitious vision for US economic ties with India, and to work closely with Indian officials on a roadmap toward that goal—with APEC a good start as a non-binding trade promotion forum, and then discussion of a free trade agreement in the longer term or Indian membership in the TPP. But for that to become possible, India will need to decide whether it wants the benefits that will come from expanded trade in a more open arrangement than those it has previously joined—and whether it is willing to make the hard choices at home to do so.