Even India thinks Indians are cramming too hard for entrance exams to elite colleges

In India, there is a sacrosanct hierarchy of academic degrees, and nothing comes close to a bachelor’s from one of the Indian Institutes of Technology. It is something to which parents aspire for their children even before they have children. The child might be a gifted writer, painter or cricketer, but preparing for the IIT examination is practically a rite of passage for any self-respecting, middle-class Indian student.

In India, there is a sacrosanct hierarchy of academic degrees, and nothing comes close to a bachelor’s from one of the Indian Institutes of Technology. It is something to which parents aspire for their children even before they have children. The child might be a gifted writer, painter or cricketer, but preparing for the IIT examination is practically a rite of passage for any self-respecting, middle-class Indian student.

And now the entrance exams might be getting a makeover.

A government-appointed committee has proposed administering a mandatory aptitude test for those interested in studying at India’s premier engineering schools. The test is meant to assess a candidate’s “scientific thinking,” and only those who display it in adequate amounts would be allowed to sit for the next, and final, examination, which would evaluate candidates’ knowledge of physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

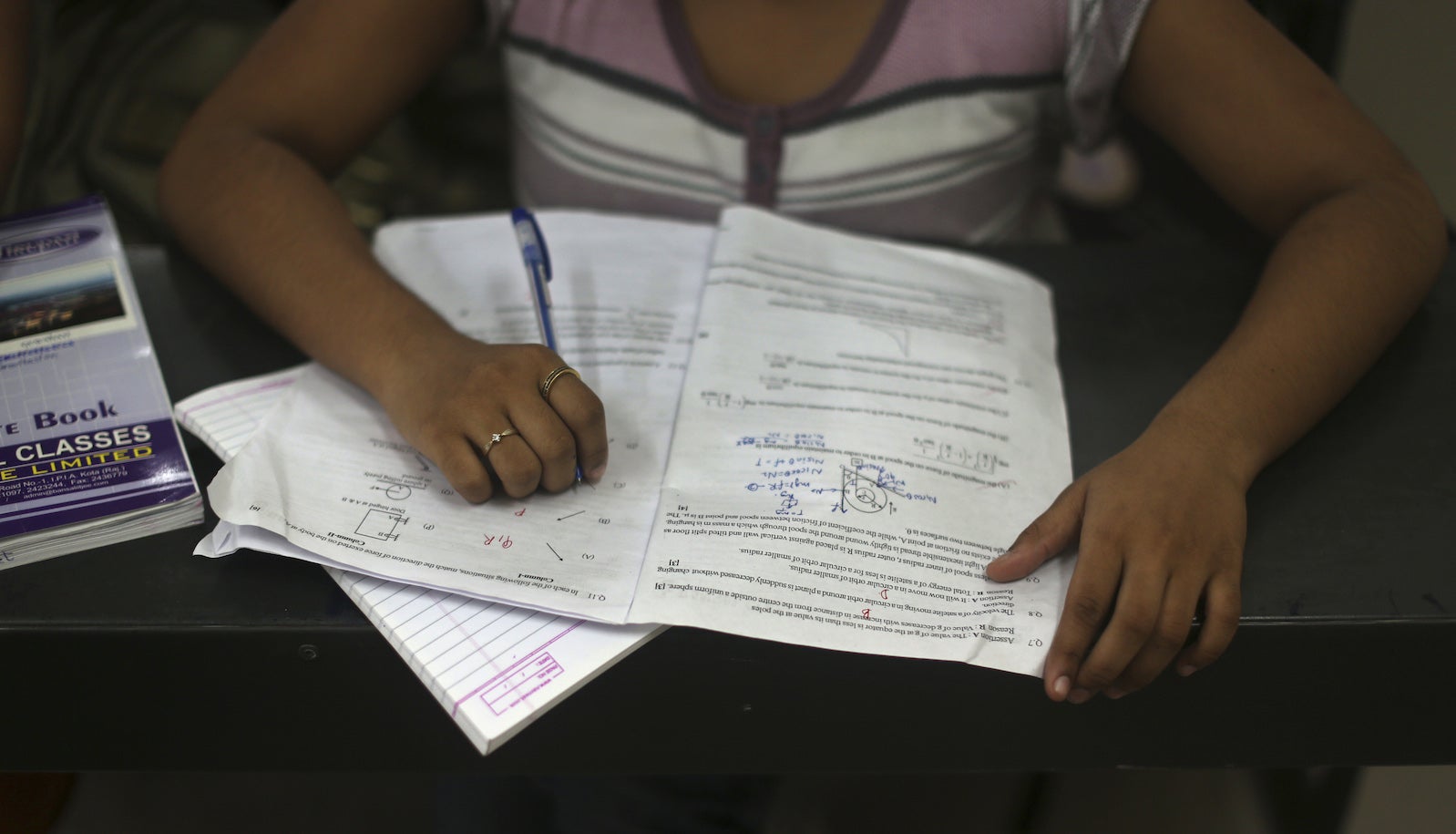

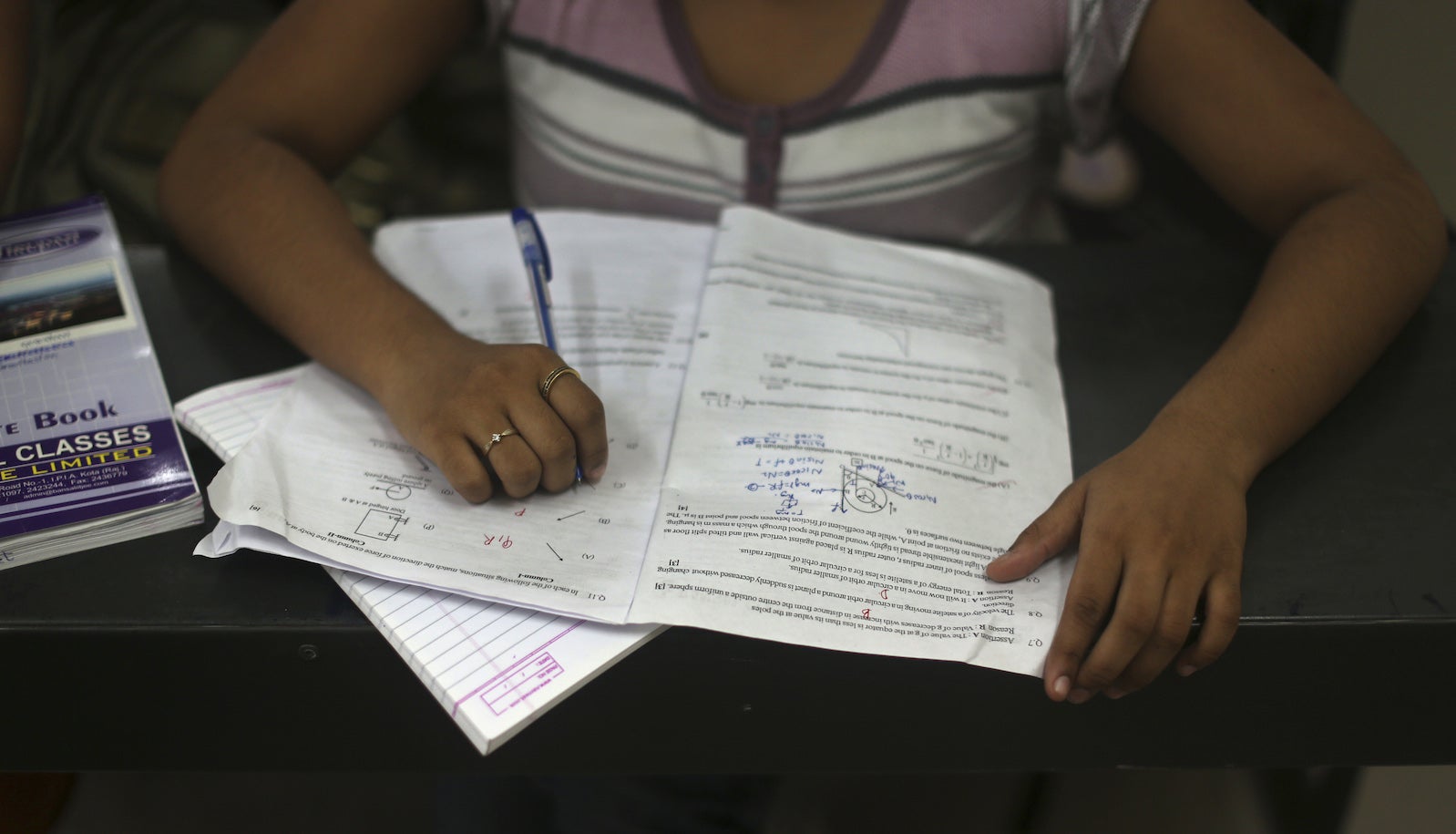

The real reason for the revamp is to get rid of cram schools—the private coaching institutes where teenagers frequently end up spending 16 hours a day attending classes, tackling mathematical problems, and polishing their skills in rote learning, in preparation for the IIT exam.

A member of the panel recommending the reforms told Business Standard that the idea “is to discourage the culture of joining coaching classes. A test that evaluates scientific aptitude could keep students and their parents away from coaching classes because one cannot be trained in aptitude.”

But here is the catch in the plan: Since when did aptitude have anything to do with our desire to get into the IITs?

Where physics is a first love

The demand for IITs—and engineering schools in general—took off in the mid-1990s, with the unshackling of India’s economy, which allowed informational and technology sectors to flourish. IT jobs promised fat salaries and American jobs, and parents left no stone unturned in preparing—some would say brainwashing—their children for the IITs.

A regular education was not deemed fit to stand up to the task. Private coaching institutes soon arrived to fill the gap; now they are part of a $6.4 billion industry.

These institutes—often costing a small fortune—offer IIT aspirants a unique version of hell. There is no time for internet, TV, sports or …fun.

“Physics is my first and last girlfriend,” a 17-year-old student in the city Kota, the jewel in the crown of India’s private coaching industry, once told me.

Thousands of children from all across India converge in Kota every year to join some of the country’s best known cram schools, which promise admissions into the most desired engineering (or medical) colleges in the country. But often students, in the absence of any real interest in science, and under unbelievable pressure from parents, crumble during these years. In Kota alone, 72 students have committed suicide in the past five years.

But for many parents and students, the horror and pain of cram schools is worth it as long as an admission in an IIT is within reach.

In this world, aptitude can be crushed, taken apart, and re-trained.

A necessary evil

The boom in coaching institutes for higher education can easily be traced back to India’s miserable primary and secondary schooling system, which suffers from chronic underinvestment.

A World Bank study in 2004 found that 25% teachers were absent from Indian schools. Subsequent surveys have found that more than half of India’s class-five students are unable to read at a class-two level.

While every government seems to promise new IITs or management colleges, little has been done to improve the quality of the school system overall. Even privately funded lower schools are unable to provide enough capable teachers in high school to prepare students for India’s intensely competitive college entrance exams. As a result, one in four students in India enroll in supplemental instruction programs—some starting from elementary-school age.

Tried earlier

This isn’t the first time a government has attempted to squash the private tuition industry that has grown up around the entrance exams to engineering schools.

“Coaching institutes have gradually replaced our secondary schools…We are creating an army of children adept at cracking examinations, but can they think critically?” the country’s former education minister, Kapil Sibal, said three years ago.

The then Congress-led government tweaked the IIT admissions process by giving weight to school performance as well. But to what end? In the past three years, enrollment rates in coaching schools have only gone up.

It doesn’t seem like that trend will reverse anytime soon, even with advent of an aptitude test. Tinkering with an exam format is easy—it’s overhauling the rest of the education system that’s hard.

An executive from a popular Kota-based cram school told the Business Standard that the panel’s recommendation “is unlikely to discourage students from flocking to coaching institutes.” All it means is that more students will now join coaching institutes to train for the aptitude test.

We welcome your ideas at [email protected].