Pakistan’s most famous nuclear scientist has found a new interest: Menopause

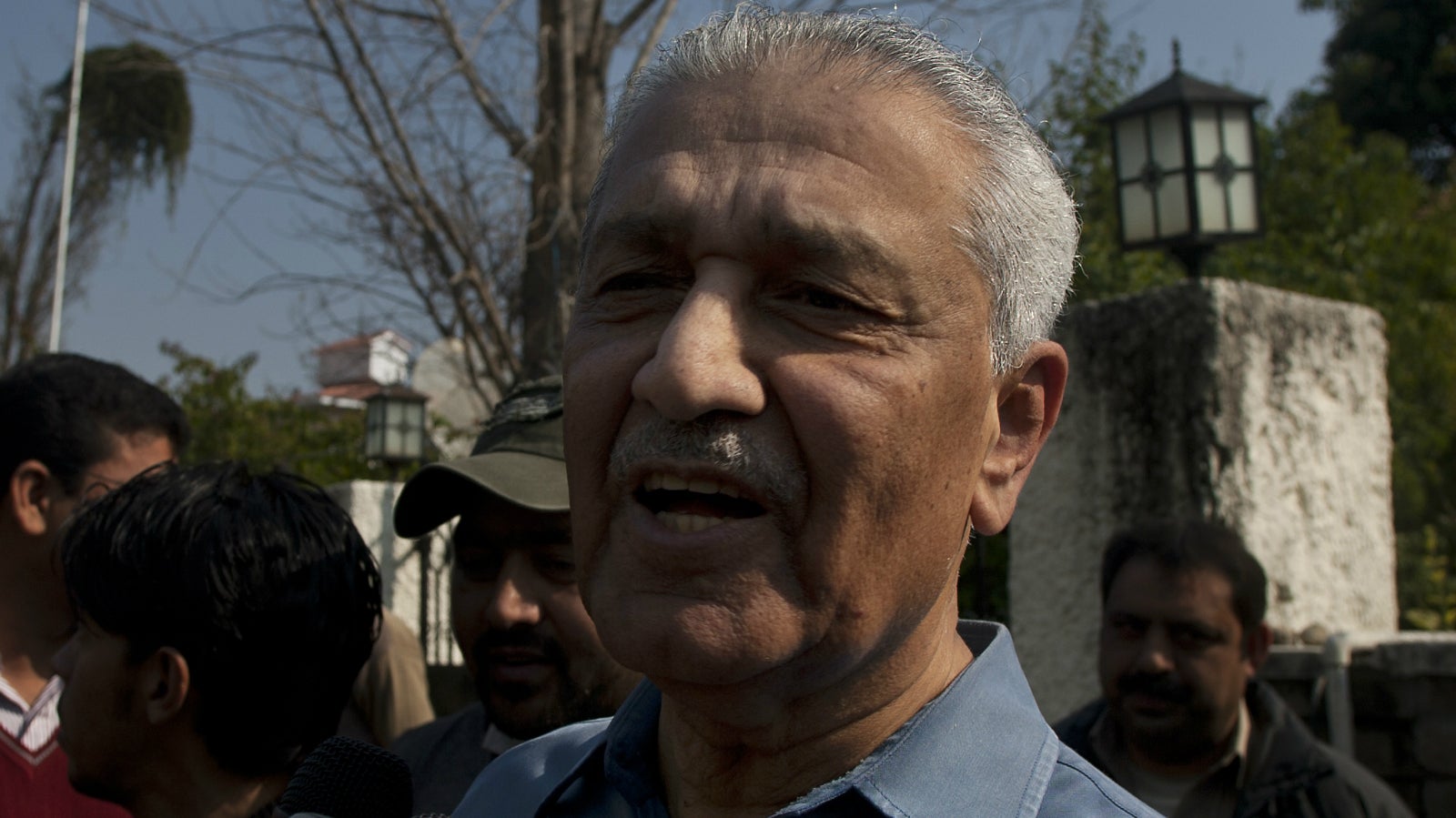

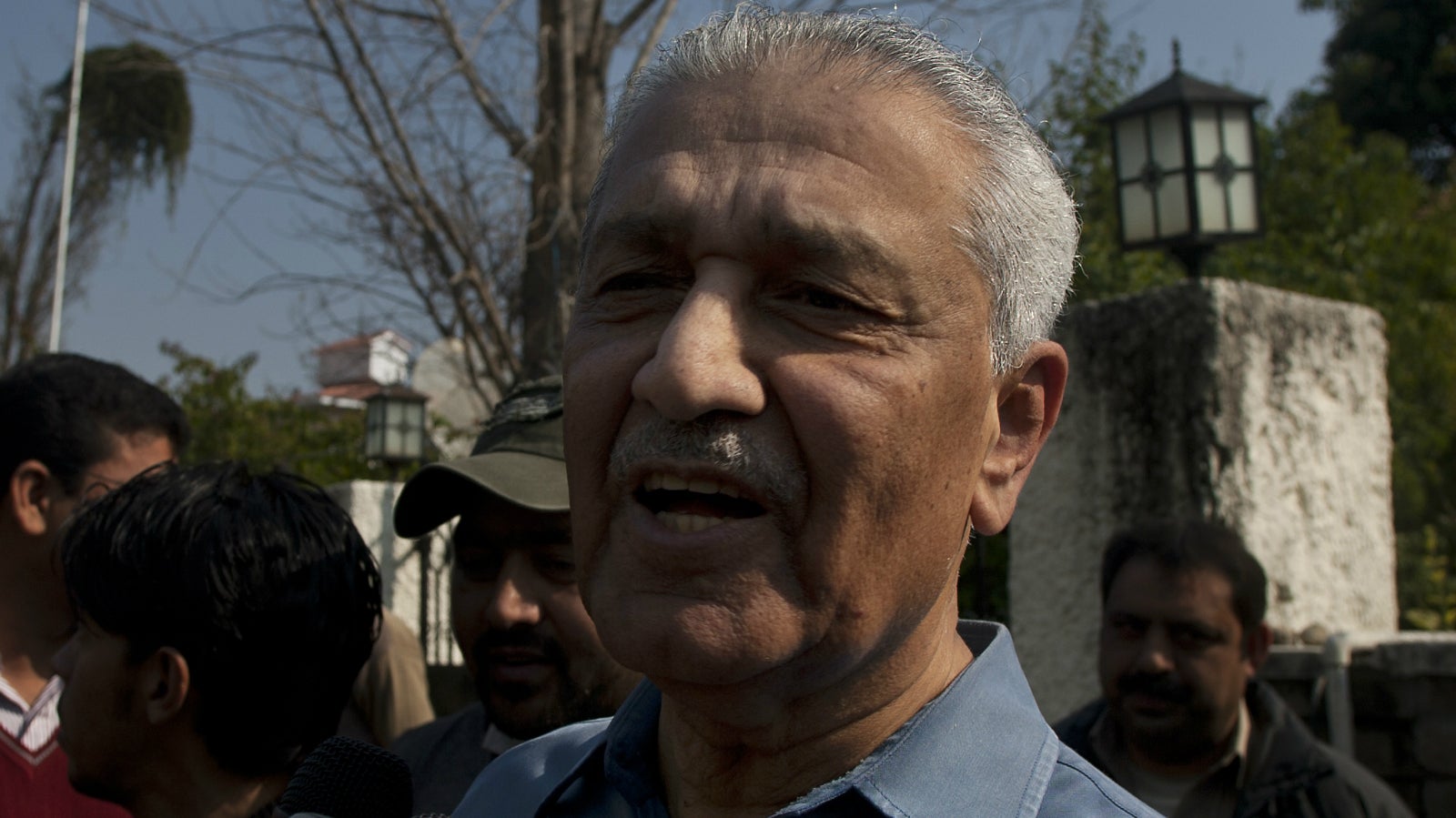

Nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan certainly does not shy away from subjects considered beyond the pale in Pakistan’s conservative society.

Nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan certainly does not shy away from subjects considered beyond the pale in Pakistan’s conservative society.

Several years earlier, the controversial Bhopal-born metallurgist who once ran Pakistan’s nuclear programme, publicly declared that he had undergone a vasectomy—a surgical procedure for male sterilisation. Khan, who also had a hand in selling nuclear secrets to Iran, Libya and North Korea, had reportedly undergone the surgery in Dubai.

“I was the first Pakistani to disclose on TV that I had undergone vasectomy after the birth of our second daughter and we felt our family was complete. We had no desire to have more children just for the sake of trying to have a son. My (controversial) statement was appreciated by many and the Family Planning Organization used it for their campaign,” Khan told Quartz in an email interview.

Now, the 79-year-old is directing his attention to another issue that is considered taboo in the Islamic nation: Menopause.

Last week, in a column for Pakistan’s The News newspaper, Khan wrote a 1,000-word article on menopause and the science behind it.

“Menopause is a very important period in a woman’s life,” Khan wrote on Nov. 16. “I was surprised that not much attention was paid to it here (in Pakistan).”

Women go through menopause when they stop menstruating permanently, often experiencing symptoms like mood swings, anxiety and depression, in addition to physical problems such as lack of energy, weight gain and joint soreness. According to the Pakistan Menopause Society, a Karachi-based organisation, the estimated age of menopause in Pakistani women is around 46 years, lower than the global average of 50.

“From the available Pakistani data, it is hypothesized that an early age of menopause predisposes a woman to chronic health disorders a decade earlier than a Caucasian women,” the society says on its website.

However, this time in a woman’s life is barely talked about in Pakistan. According to Khan, on Oct. 18, marked as the World Menopause Day, only “two useful articles” were written about this natural change in Pakistani mainstream media.

“In the western world, discussing menopause, menstruation, etc. is not taboo and mothers usually inform their daughters about these matters at an early age. Even contraception is often discussed,” Khan said. ”My wife, being of Dutch origin, explained these things to our daughters long before they reached puberty. As a family, we are quite open and can discuss these natural phenomena.”

Khan hopes to bring the same kind of openness to the Pakistani society. Over the next two weeks, he plans to write two more articles on menstrual health and menopause.

The winner of Pakistan’s highest civilian award—Nishan-e-Imtiaz—hopes that many will find “information (and perhaps, some comfort) in what has been written.”

“I am aware that it is an extremely important phase in a woman’s life and it can sometimes lead to consequences such as divorce, suicide, and disruption of family life,” Khan said.

Even though Khan was placed under house arrest for five years after being caught in the world’s biggest nuclear proliferation scandal in 2004, he still enjoys the status of a national hero among many Pakistanis. And although he will certainly manage to generate a conversation around menopause, it is unlikely to change much in a deeply conservative society.

“Unfortunately, the Urdu daily in which the Urdu version of my column is published simultaneously with the English one, apologetically informed me that the article would not be published as they considered the topic unsuited for young, innocent girls,” Khan said.

He is still optimistic.

“Things will need time to change. For instance, some years ago the words ‘breast cancer’ could not be mentioned out loud; now it is a topic that is out in the open. I hope my articles do make a dent in the wall of ignorance.”