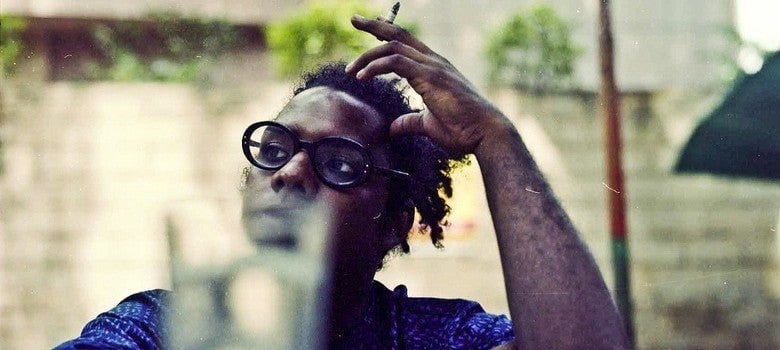

“People like him do drugs, have a high sex drive”: A Nigerian-Indian takes an auto ride in Bengaluru

Over the past few years, I’ve stopped keeping track of news on a daily basis. No good seems to come from it. As a result, I’m the last to know about anything.

Over the past few years, I’ve stopped keeping track of news on a daily basis. No good seems to come from it. As a result, I’m the last to know about anything.

Last Wednesday (Feb. 03), while I was running around on a writing assignment in my hometown of Bengaluru, my editors from Mumbai called me to ask whether I was safe. I wasn’t sure what exactly they meant, so they quickly relayed the news—a Tanzanian girl, beaten, stripped, and paraded naked by a mob in my city with the police standing by silently—and impressed upon me the need to be careful. My initial response: unbridled laughter. I wasn’t laughing because I found the heinous incident funny but because it was happening again. As a queer person with one parent who is Nigerian and the other Indian, I was being violently reminded that it’s dangerous to be different in India.

Though I was slightly shaken by the news of the attack, I am determined to think of myself as the local I am and ignored my editors’ request to travel only by cab over the next few days. I caught an auto-rickshaw, but it seemed like the city was determined to teach me a lesson. The auto driver turned out to be a Kannada chauvinist, who insisted on interrogating me about the reason I had learned the language, constantly checked my knowledge about the route, and generally rode in a jerky, speedy, nonchalant fashion.

This kind of needling from macho auto drivers is common and expected, but in the light of the recent incident, his showy and reckless driving made me aware of the attention it was bringing to me. At the next stop signal, two bikes halted on either side of the auto, suddenly there were four pairs of eyes from behind helmets staring into the auto, looking me up and down. In a few seconds, the four men and the driver began to discuss me in Kannada. They were wondered about “his rate”, “whether he was a boy or a girl”, “the origin of people like him”, and insisted “that people like him with curly and rope-like hair do drugs and have a very high sex drive”. I listened silently, astonished that despite speaking Kannada to the driver, he wasn’t at the least affected by the banter. In fact, he participated quite actively in the conversation. I was rattled enough not to take the ride all the way to my apartment gate.

“These things keep happening to you,” is one of the most common responses to my retelling stories of these kinds of experiences. People don’t seem to realise that the fact that I have these kinds of experiences is a problem in the first place. I’d rather have had an uneventful, boring auto ride like everybody else. Or walk down the road without someone shouting, “African” at least once every day. Yes, I’ve learned to carry on with my life, to ignore these voices, and have even protected myself from hands trying to invade my personal space or mark my body. But it’s tiring and bloody exhausting.

Nobody should live with this feeling of being targeted. But the reasons for being attacked are increasing. They could be anything from being black to beef-eating. I thought Bengaluru was safe but that isn’t the case anymore. These incidents are happening too often to be ignored. We can’t even turn to the police for help, because they’re the biggest perpetrators of these crimes.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].