Where speaking English like non-Indians takes you places…

Surely, you’ve noticed. Indians, however good in any other Indian language, inevitably talk to their waiters, and their dogs, in English. The restaurant may be below average, forget high-end, but try placing the order in Hindi, which you know the waiter is better at, and he’ll still reply to you in English: Yes, sir. No, sir. Sorry, sir, we don’t have Pepsi, we have Coke.

Surely, you’ve noticed. Indians, however good in any other Indian language, inevitably talk to their waiters, and their dogs, in English. The restaurant may be below average, forget high-end, but try placing the order in Hindi, which you know the waiter is better at, and he’ll still reply to you in English: Yes, sir. No, sir. Sorry, sir, we don’t have Pepsi, we have Coke.

In a country largely Hindu or Muslim by faith, the population of pet dogs or cats appear alarmingly Christian by birth. You’re unlikely to have heard an owner call out to Pappu, his Pomeranian, “Jaa, ball leke aa.” It’s usually Tommy who must fetch the ball, while Mehra sahib goes back to his Punjabi with friends. Aamir Khan’s farmhouse pup Shah Rukh, by the way, is a demographic exception.

Having purebred pets at home, or dining at a restaurant, indicates social class. English denotes that arrival. The hospitality industry knows this. So what if the popular bar in Manipal gets called “Bachchoos” (like an endearment for kids) by locals, while it’s actually named Bacchus (after the Greek god of wine)? Even the staff in Patna’s top hotel Panache (for style), refer to their place of work to guests as “Panchee” (for a bird). What’s in a name, then? Plenty, if it sounds suitably foreign. New buildings called Carlton, Poseidon, Oculus, and Acropolis equally confuse the security guard at gates of massive constructions in New India. The guard can’t guide you to the building that is right next to him when you ask for directions. He can’t, in the name of God, remember what his building is called.

Besides a small Anglo-Indian community that traces half its bloodline to the British, and many Christian families that accessed the language through religion, Indians largely learnt their English either at schools and colleges or through books and newspapers. Some, more lately, learnt it first from their parents, who in turn had absorbed it from school-texts and popular reading. This is why we read better than we speak, and often speak the way we read. You can usually tell an Indian who’s “out of station” on a hot day, “perspiring” as he “purchases” things, and while bargaining, probably makes his case with an “until and unless.”

There are an estimated 100 million English speakers in India. They make for engines of the country’s economic growth by virtue of that facility alone. The world loves us for them, because the West can do business with us with much ease. Clients are relatively satisfied. Some kids mug up foreign accents at call centres. Professional emails flying all over the world from India deserve a “kind revertal” before you can do the “needful.”

How relatively poor we are at speaking the language itself usually escapes the stunning multi-million dollar statistic. We only get poorer still for the shame attached to not speaking it supposedly right. Grammar for the educated Indian got etched in stone in a little red book called the Wren And Martin, written for British officers’ children in India (including today’s Pakistan, and Burma) back in 1935. It’s still followed in certain Indian schools. At least their much older alumni swear by it. Even your girlfriend won’t spare you if you got a word or sentence wrong, or said it the way it’s apparently not to be. Others will only scoff.

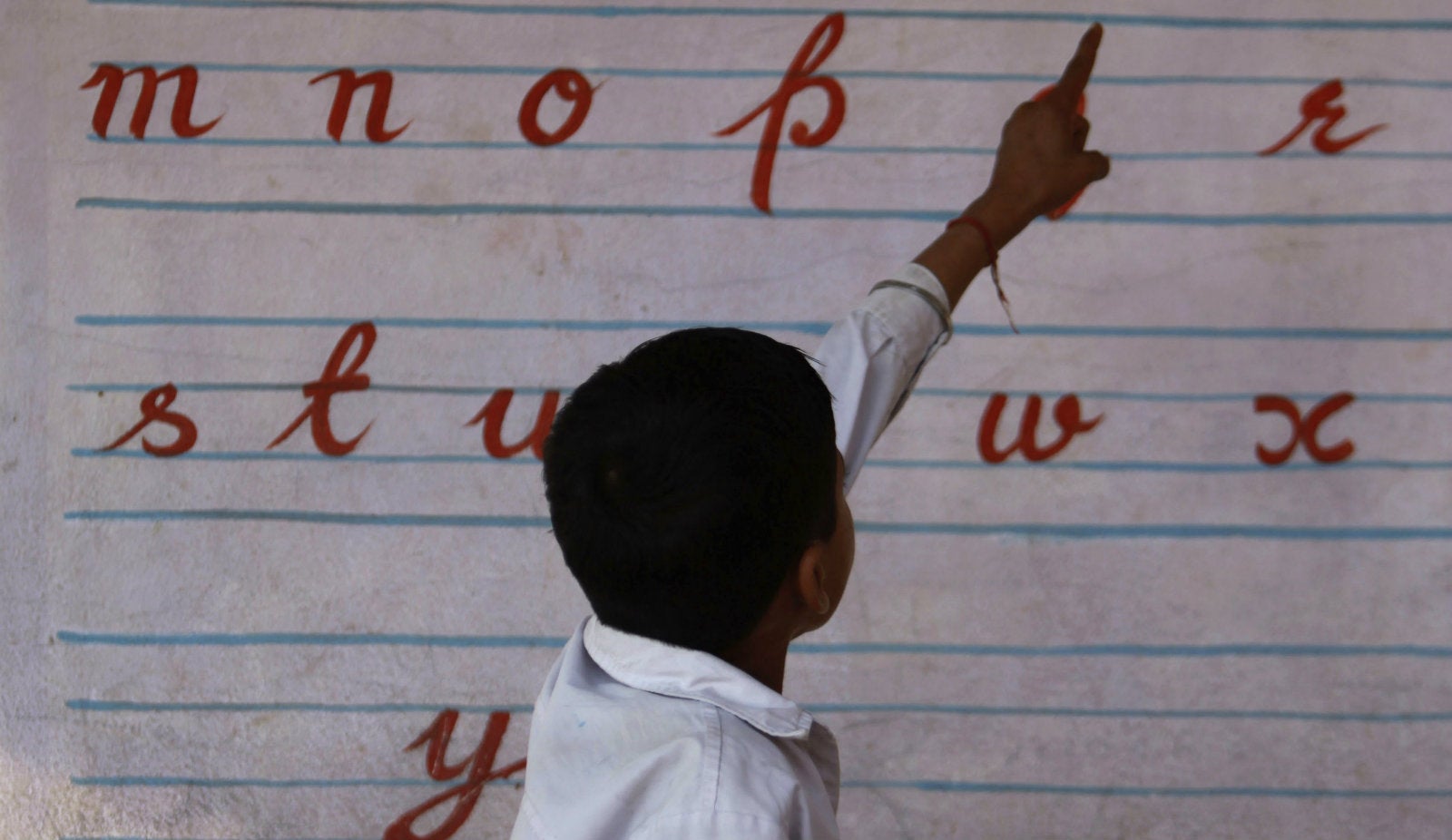

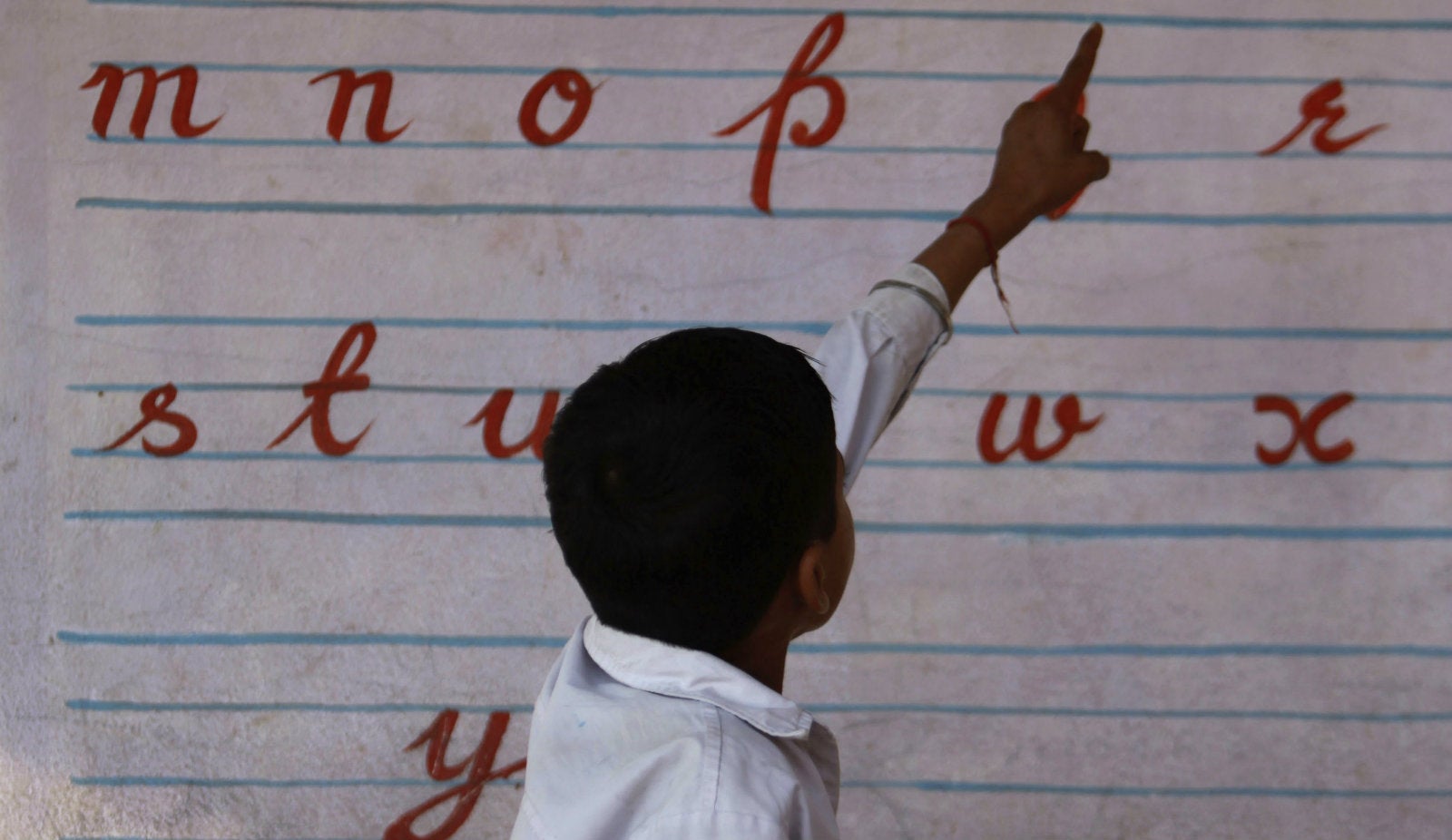

A disease of correcting everyone when they talk in English starts early for urban Indians—right from the time when the sternly Anglicised Mrs. Dhingra or Ms. Daisy spank us in primary school for saying “vauter” and not “wohter”: rounding the lips adequately and stroking the tongue hard enough to capture a tingly “t.” Scarred since childhood, most, I observe, hardly become adult about such matters.

There is no legit thing as a proper Indian English accent either. It remains still an enduring gag. Indian Younglish is an illegitimate twang, a strange progeny of our love for both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The sentences could begin with a “Yo”, borrowed from a New York hood, and conclude with a peculiarly British intonation, “Yeah?” picked up from a London quarter. I alternate between American and British Indian spellings while writing, because sweet we are like that!

If anything, the young are more influenced by American pop-culture, as against their parents who aped the old Brits. Hinglish, a liberal mix of Hindi and English, chutnified by popular Indian entertainment—Bollywood and music television in particular—bears neither the burden of being English nor Hindi. Unchecked, it is creatively dynamic, and flourishes, as it should.

All other Indian languages, mother tongue for most, are phonetic by nature. This compounds a peculiar “B-U-T but, but P-U-T put” problem for the Indian. You’ll speak even less of English for fear of mispronouncing a word, or stringing an incorrect sentence. A few incorrect words here and there immediately show themselves off as a sign of social inferiority. One guards against being termed ghati. This causes a fundamental gap even between parents who’ve had a provincial upbringing and their children who grew up learning English from a really young age.

Knowing an indigenous Indian language really well, bears few social rewards. A novice won’t practice English in public for fear of being ridiculed. Being unable to practice with those better at the game makes you worse at it still. It is hard to develop an acceptable Indian way of speaking the language. You can mess with your mother. You can’t upset the Queen.

“Prepone”, as the opposite for “postpone”, is understood by all. It’s still rejected by custodians of Indian English. This is not on, you see. “Budday” as pronunciation for birthday is plainly inappropriate, though the whole country calls it so, and “backside” for “behind” is a similar marker for desi crude. “Hotel” is evidently the Indian word for restaurant as is “marketing” for shopping and “programme” for plan. They’ll never make it to any English dictionary, because we would’ve stopped ourselves from saying it before the word’s out.

Inferiority complex of a few for years killed the basic excitement of many millions from fitting in better with English as their own second language. You can learn words in school. It will bring you jobs. Speaking those words the way some think you must truly promises social mobility. Accents in tiny Britain change from one town to another. Indians are meant to adhere to a common set of “received pronunciation.”

The urban desi takes incredible pride in mocking the Gujarati, Punjabi, Tamilian, Bengali, or Bihari English accents, grouping these unfortunate wannabes as “vernies” or vernaculars (those more at peace with a regional tongue). Self-appointed linguistically superior Indians don’t just communicate with each other in English. They barter strong self-esteems, snobbery of the empire (British or American), a common parentage and combined GDPs through a social communication programme.

Politicians usually benefit from such bald elitism. It is their job to spot social schisms. Netajis of Samajwadi Party, a major political outfit in the Hindi heartland Uttar Pradesh, used to routinely stick their middle finger out at the disconnected babalog (rich, English speaking, western educated, city-bred young), who inherited politics from parents who were more firmly rooted to the local soil. They understand the poor voter’s deep resentment against the exclusive condescending club. It’s a lateral divide arguably more real than caste or religion.

SP (the Samajwadi Party; not the cop who insists on talking in Marathi in Bombay) would occasionally demand limiting the use of English in education. It’s an old seventies’ style rhetoric. At some point in the India of the new millennium, parents started to reject the Hindi lover’s swadeshi logic. They realised their children were better off mastering a global language, moving up, or at least moving out of a place that birthed dark politics of hate and little else.

Lower castes in certain towns of Uttar Pradesh now mark October 25 as “English day.” In a temple, they actually worship a certain Dalit deity they call English. October 25 is the birthday of Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay. Among other things, he’s credited with having enforced English education in Indian schools and colleges in the mid-19th century. Generations of Indians have since derided the British imperialist Macaulay for his racist stance against Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit and other Indian languages, breeding a brood of babus, brown sahibs or “Macaulay’s children” who continued to rule as administrators, dominating the civil services, even after the British left.

Dalits in these regions of Uttar Pradesh, in fact, now consider Hindustani as the language of the oppressor. Their ancestors were denied Sanskrit first. English bears the promise of freeing them from their caste. It empowers them to deal directly with the world. That much-mystified patron saint of Dalits, B.R. Ambedkar, many believe, wouldn’t have become Babasaheb if it weren’t for an English education. They will probably learn about the silly caste system that exists among English-speaking Indians, I guess, only after they’ve learnt the language first.

Samajwadi Party, ever the masterful opportunists at gauging public moods, realised their anti-English rhetoric had totally flopped. The other thing the party decided to dislike thereafter was the computer. In its own right, it’s a form of communication that neatly splices the world into young and old, and within the young between the haves and have-nots. Those who are poor can still see the computer as a legitimate ladder to climb up and survey the world from rather than be perennially left behind. Few years later, the Samajwadis, sensing their bigotry was not going to yield any democratic dividend, began to distribute free laptops to their electorate instead. But they were smart enough to have anticipated an important divide.

The next serious social split in India, as anywhere else, might just come from one’s facility or lack thereof with the computer—the software mart, Internet, apps, tabs and much else. Digitally illiterate parents may not understand their children too well, only few years after the kids are born, unless they simultaneously upgrade their understanding of the ever-expanding virtual universe.

But that merely takes some practice on the keyboard to champion. Unlike English, and the way you must strictly write or speak it and be judged forever for, this divide is easier to overcome. Or well, maybe not, given how often I feel like an ignoramus loser among those only few years younger than me furiously juggling between various windows and files on their screen, swiftly travelling to unknown corners of the web, downloading the whole world into their hard disk. My fancy comp already feels like a typewriter next to theirs.

Excerpted from Mayank Shekhar’s Name, Place, Animal, Thing, published by Fingerprint. We welcome your comments at [email protected].