Stuck in Bengaluru’s insane traffic, Uber and Ola drivers are losing their incomes—and health

This post has been updated.

This post has been updated.

It’s just shy of 9 o’ clock on a warm Monday morning in March, but Brigade Road, in the heart of Bengaluru’s commercial district, is already jam-packed.

The sun beats down mercilessly, and inside their unmoving cars, people crank up their air conditioners, settle back into their seats, and stare into their smartphones with a resigned air. In Bengaluru, this is the new normal.

Ola driver Lokesh Naidu’s white Toyota Etios is sandwiched between a Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation bus and a shiny black Audi in the middle of the Brigade Road traffic jam. Naidu, a swarthy local with a thick moustache, mops the sweat off his considerable forehead with his sleeve and drums his fingers impatiently on the steering wheel. He’s had two early-morning airport drops that took forever, and this is his third pickup today. “Saar, it’s good you only go short distance,” he says. “Yesterday, I am only doing five rides in the city. No incentive.” He shakes his head vigorously.

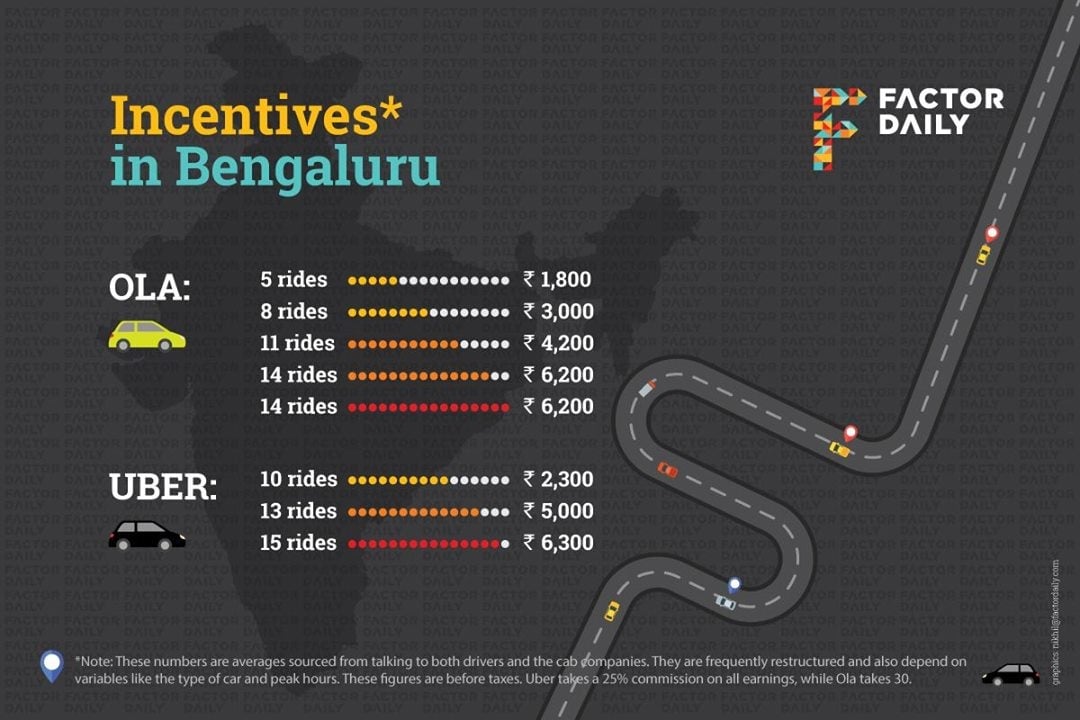

Incentives are payouts that Ola and Uber, the country’s biggest app-based taxi platforms, hand out to drivers on top of what they make from each ride. They kick in once a driver completes a certain number of rides each day, and are the proverbial carrot at the end of the stick to get cab drivers to accept just one (or a few) more rides to hit sweet, sweet pay dirt. A Bloomberg report published last year claimed that Uber drivers in India earn more than some bankers, thanks to incentives.

In theory, this system keeps everyone happy—you get picked up faster, drivers get more cash, and taxi companies get Jupiter-sized investments. But if you’re a driver in Bengaluru, things aren’t that simple.

India’s IT capital is growing faster than anyone or anything can keep up. Since March 2015, the number of registered vehicles in the city has gone up from 55.59 lakh vehicles to more than 60 lakh as of January 2016 according to data from the Bengaluru RTO. In fact, the number of vehicles in Bengaluru is increasing at 10% each month. Bengaluru is now second only to New Delhi—a city with a robust metro system that transports over 2.3 million riders daily—in terms of the number of vehicles plying. And with average speeds of 18 kph, it has achieved the distinction of being one of the the country’s slowest metros.

The fallout? For cab drivers, hitting the minimum number of rides required each day to get a reasonable incentive is getting tougher every single day.

“Daily 14-15 trips nahi hota hai Bangalore mein” (I can’t do 14-15 trips a day in Bengaluru) says Mahesh K C, who has been driving for Uber for six months and makes about Rs40,000 each month after Uber’s 25% cut, the EMI for his car, fuel, and maintenance. Before Uber, K C used to work as a private driver in Bengaluru where he made about Rs25,000 each month. “Money was less but no tension there,” he says. “Here there is constant tension of incentives. Oh, I have only finished five rides, I need seven, eight more.”

K C manages to meet his personal target of 13 trips a day only on weekends because traffic is relatively less. The incentive system is unfair, he says, because it doesn’t take the distance or the duration of a ride into account. “Two kilometre ride, 20 kilometre ride, 15 minute ride, one hour ride, all same thing,” he says. “It’s not good.”

Uber introduced incentives to ensure that drivers’ incomes remain relatively stable and are not severely impacted by volatile demand and supply, a company spokeswoman told me. In smaller cities, where demand may not be as high, Uber looks at multiple data points like the size of the city and vehicle congestion before coming up with an incentive structure. “We also rethink the incentive structure from time to time if we think drivers in a particular city aren’t making enough money,” she said.

Uber did not specify how frequently this structure changes, but a Bengaluru driver, who wished to remain anonymous, said that he gets a message about new incentives almost every night. The trouble, he says, is that the number of rides required to get an incentive never changes. “Sirf incentive kabhi 200-300 rupees se kam-jyaada hota hai.” (Only the incentive amount goes up or down by Rs200-300).

That’s a serious issue in a congested city like Bengaluru. More than a dozen drivers for both Uber and Ola told me that they were waking up earlier and earlier every day to meet the incentive target. Ola driver Naidu says he drives nearly 19 hours a day to complete 16 rides, the highest number you can do to get an incentive. “If I don’t start at five in the morning, 16 rides don’t happen,” he says, adding that he has been unable to finish more than eight rides in an eight-hour workday.

Naidu, who is paying off a car loan and saving up for his wedding, says that the pressure to make money from incentives is intense, especially since Ola takes 30% of all driver earnings. “No Sunday, no Saturday, no Wednesday, no nothing. Every day I drive,” he says.

Naidu’s days are an endless blur of Bengaluru’s crowded streets. His three meals a day are spaced wide apart: a light breakfast of rice and milk when he wakes up at 4 am; lunch, usually a dosa from a roadside shack at 3 pm; and a chicken dinner washed down with a quarter of Royal Stag around midnight when he gets back to his one-bedroom house in suburban Whitefield, nearly 20 km from downtown Bengaluru. “I’m so tired, saar, I can’t sleep without a quarter,” he says with a laugh.

Driver fatigue is a tragic fallout of the on-demand taxi industry. In February, Uber limited drivers in New York to 12-hour shifts after an 88-year-old woman in the city’s Upper West Side was killed by a driver who had been driving for 16 hours continuously.

Uber didn’t put any such restrictions on drivers in India even after a driver killed a cyclist on Bengaluru’s International Airport Road last month after driving for 14 hours straight.

“We don’t tell them that they have to work a fixed number of hours each day in India,” said the Uber spokeswoman. In Uber’s Indian system, overworking drivers don’t show up until someone in the company manually runs a query.

A Bengaluru traffic official told The Hindu that it was up to cab companies to ensure that their drivers follow government-mandated labour laws. But that’s where the catch is. India’s Motor Vehicles Workers Act of 1961 caps the number of hours of work for professional drivers at 8 hours a day and 48 hours a week—but drivers who work on Uber and Ola’s platforms are not employees. “They are merely independant contractors,” says Jaspal Singh of Valoriser Consultants who has consulted independently for both companies in the past.

Ola did not respond to our questions despite multiple attempts.

Siddegowda, who has been an Uber driver for just four months, says that 10 trips a day—the minimum number required to get an incentive from Uber—is the most he can complete on any given day. “Kal subah 4 baje se raat 11 baje tak 10 trips hua. Ek bhi minute phone off nahi kiya tha” he says. (I completed 10 trips from four in the morning to eleven at night yesterday. I didn’t switch my phone off for even a single minute).

Twenty-four-year-old Shivane Gowda, who chucked up his job as a chauffeur for a wealthy Bengaluru businessman a year ago to drive for Ola says that he tries “very, very hard” to finish 16 rides a day. “But Bangalore mein bahut jyaada gaadi ho gaya hai. (But the number of vehicles in Bangalore has increased). It’s getting worse worse worse! Zero improvement,” he says.

Gowda once got a ride from Whitefield to Bengaluru’s Kempegowda Bus Terminal, a distance of about 25 km, that took him nearly half a day to cover. “No incentive that day,” he says with a shake of his head, and adds that he gets no more than five hours of sleep each night. Doesn’t he feel drowsy while driving? “Haan, but kya kare sir, family problem hai. Paise ki jaroorat hai” (Yes, but what can I do, sir, I have a family problem. I need the money ).

For the last six months, Gowda has been experiencing shooting pains from the base of his right heel all the way up to his knee. He hasn’t been to a doctor because he can’t afford one, he says. Besides, he knows exactly what the problem is. “I press down the accelerator with my foot 18 hours a day,” he says. “Kya bolenge doctor? Rest karo, rest karo. (What will the doctor say? Rest). That I can’t do. Bahut jyada pain, I take painkillers. Bas.” (If there’s too much pain, I take painkillers, that’s it).

So what’s the solution? Unless on-demand cab companies become more sensitive to the rigours that their policies put their contractors through, they are putting both the people who keep them in business by working on their platforms as well as their customers at great risk.

“Work hours flexible hai,” (The work hours are flexible) says Gowda. “Par 8-10 ghante chalane se baat nahi banti.” (But driving for just 8-10 hours isn’t feasible).

This post was first published by FactorDaily, which covers the intersection of technology and culture in India. We welcome your comments at [email protected].

Correction: In the earlier version, FactorDaily said the number of registered vehicles in Bengaluru went up to more than 1.2 crore in January 2016. Actually, the number has gone up to 60 lakh.