The unlikely friendship that uncovered an untrained Indian mathematician’s genius

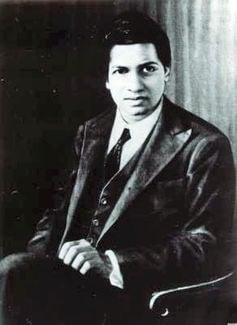

Throughout the history of mathematics, there has been no one remotely like Srinivasa Ramanujan. There is no doubt that he was a great mathematician, but had he had simply a good university education and been taught by a good professor in his field, we wouldn’t have a film about him.

Throughout the history of mathematics, there has been no one remotely like Srinivasa Ramanujan. There is no doubt that he was a great mathematician, but had he had simply a good university education and been taught by a good professor in his field, we wouldn’t have a film about him.

As the years pass, I admire more and more the astonishing body of work Ramanujan produced in India before he made contact with any top mathematicians. Not because the results he got at the time changed the face of mathematics—far from it—but because, working by himself, he fearlessly attacked many important and some not so important problems in analysis and, especially, number theory—simply for the love of mathematics.

However, the role played by Ramanujan’s tutor Godfrey Harold Hardy in his life story cannot be understated. The Cambridge mathematician worked tirelessly with the Indian genius, to tame his creativity within the then current understanding of the field. It was only with Hardy’s care and mentoring that Ramanujan became the scholar we know him as today.

Determined and obsessed

In December 1903, at the age of 16, Ramanujan passed the matriculation exam for the University of Madras. But as he concentrated on mathematics to the exclusion of all other subjects, he did not progress beyond the second year. In 1909, he married a nine-year-old girl but failed to secure any steady income until the beginning of 1912, when he became a clerk at the Madras Port Trust office on a meagre salary.

All this time, Ramanujan remained obsessed with mathematics and kept working on continued fractions, divergent series, elliptic integrals, hypergeometric series and the distribution of primes. By 1911, Ramanujan was desperate to gain recognition from leading mathematicians, especially those in England. So, at the beginning of 1913, when he was just past 25, he dispatched a letter to Hardy in Cambridge with a long list of his discoveries—a letter which changed both their lives.

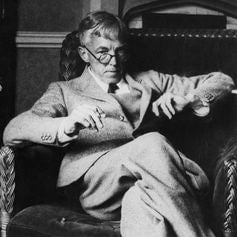

Although only 36 when he received Ramanujan’s letter, Hardy was already the leading mathematician in England. The mathematical scene in England in the first half of the 20th century was dominated by Hardy and another titan of Trinity College, J.E. Littlewood. The two formed a legendary partnership, unique to this day, writing an astounding 100 joint papers. They were instrumental in turning England into a superpower in mathematics, especially in number theory and analysis.

Hardy was not the first mathematician to whom Ramanujan had sent his results, however the first two to whom he had written judged him to be a crank. But Hardy was not only an outstanding mathematician, he was also a wonderful teacher, eager to nurture talent.

Genius unknown

After dinner in Trinity one evening, some of the fellows adjourned to the combination room. Over their claret and port Hardy mentioned to Littlewood some of the claims he had received in the mail from an unknown Indian. Some assertions they knew well, others they could prove, others they could disprove, but many they found not only fascinating and unusual but also impossible to resolve.

It was clear to Hardy that Ramanujan was totally exceptional: however, in spite of his amazing feats in mathematics, he lacked the basic tools of the trade of a professional mathematician. Hardy knew that if Ramanujan was to fulfil his potential, he had to have a solid foundation in mathematics, at least as much as the best Cambridge graduates.

This toing and froing between Hardy and Littlewood continued the next day and beyond, and soon they were convinced that their correspondent was a genius. So Hardy sent an encouraging reply to Ramanujan, which led to a frequent exchange of letters.

It was for Ramanujan’s good that Hardy invited him to Cambridge, then, and he was taken aback when, due to caste prejudices, Ramanujan did not jump at the chance. As a Brahmin, Ramanujan was not allowed to cross the ocean and his mother was totally opposed to the idea of the voyage. When, in early 1914, Ramanujan gained his mother’s consent, Hardy swung into action. He asked E.H Neville, another fellow of Trinity College, who was on a serendipitous trip to Madras, to secure Ramanujan a scholarship from the University of Madras. Neville wrote in a letter to the university that “the discovery of the genius of S. Ramanujan of Madras promises to be the most interesting event of our time in the mathematical world …”

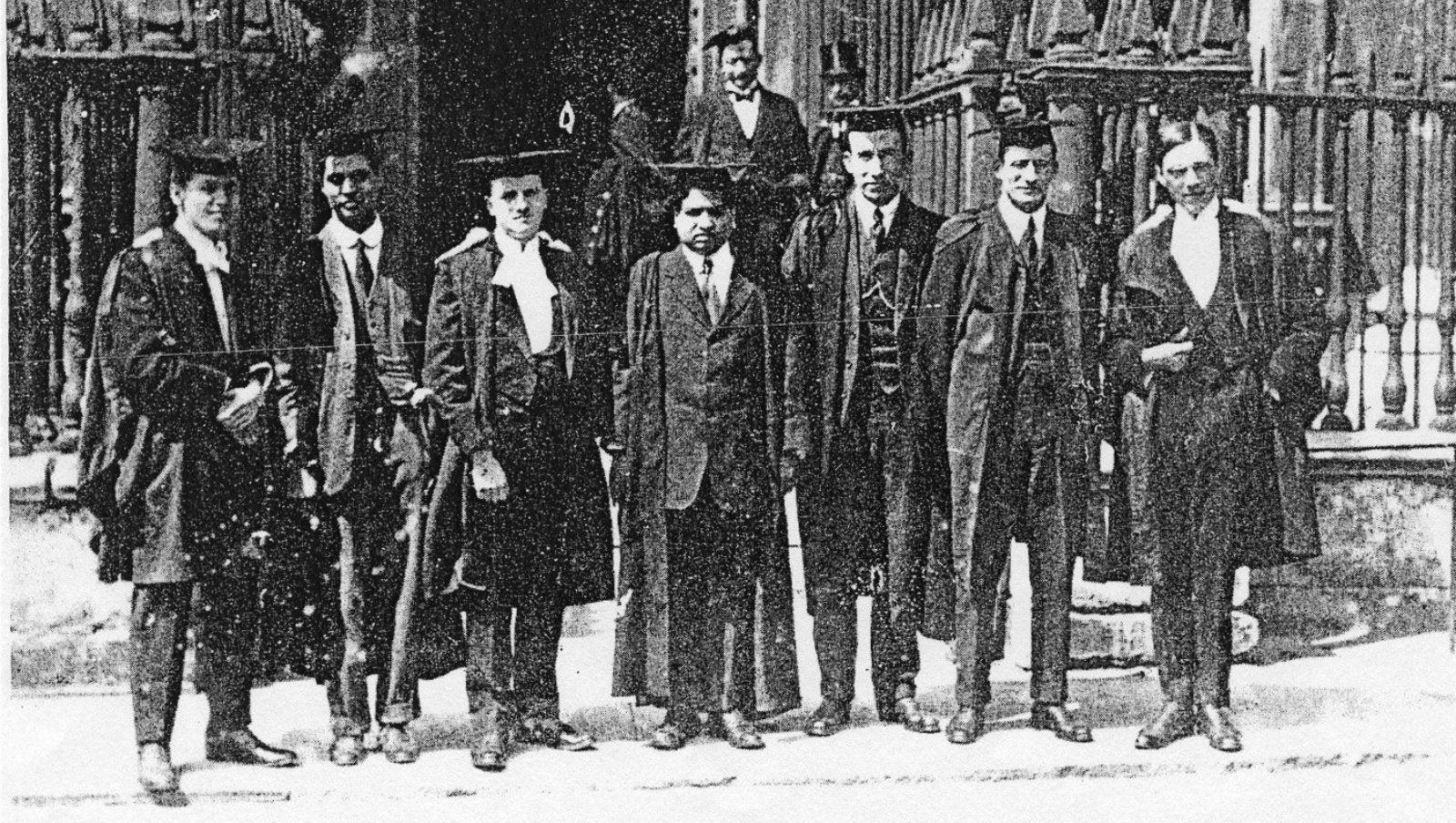

Ramanujan sailed for England in the company of Neville, and arrived in Cambridge in April 1914.

Fearless mentoring

I cannot but admire Hardy for his care in mentoring Ramanujan. His main worry was how to teach this astounding talent much mathematics without destroying his confidence. The last thing Hardy wanted was to dent Ramanujan’s fearless approach to the most difficult problems. To quote Hardy:

The limitations of his knowledge were as startling as its profundity. Here was a man who could work out modular equations, and theorems of complex multiplication, to orders unheard of, whose mastery of continued fractions was, on the formal side at any rate, beyond that of any mathematician in the world … It was impossible to ask such a man to submit to systematic instruction, to try to learn mathematics from the beginning once more.

On the other hand there were things of which it was impossible that he would remain in ignorance … so I had to try to teach him, and in a measure I succeeded, though I obviously learnt from him much more than he learnt from me.

For almost three years, things went extremely well. In 1916 Ramanujan got his BA from Cambridge and his research went from strength to strength. He published one excellent paper after another, with a great deal of Hardy’s help in the proofs and presentation. They also collaborated on several great projects, and published wonderful joint papers. Sadly, in the spring of 1917 Ramanujan fell ill, and was in and out of sanatoria for the rest of his stay in Cambridge.

By early 1919 Ramanujan seemed to have recovered sufficiently and decided to travel back to India. Hardy was alarmed not to have heard from him for a considerable time, but a letter in February 1920 made it clear that Ramanujan was very active in research.

Ramanujan’s letter contained some examples of his latest discovery, mock theta functions, which have turned out to be very important. A main conjecture about them was solved 80 years later, and these functions are now seen as interesting examples of a much larger class of mock modular forms in mathematics, which have applications to elliptic curves, Borcherds products, Eichler cohomology and Galois representations—and the nature of black holes.

Sadly, Ramanujan’s recovery was short-lived. His illness returned and killed him, aged just 32, on April 26, 1920, leaving him only a short time to benefit from his fellowship of the Royal Society and fellowship of Trinity.

Ramanujan’s death at the height of his powers was a tremendous blow to mathematics. His like may never be seen again, and certainly such a partnership as that which Hardy and Ramanujan built will not either.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.