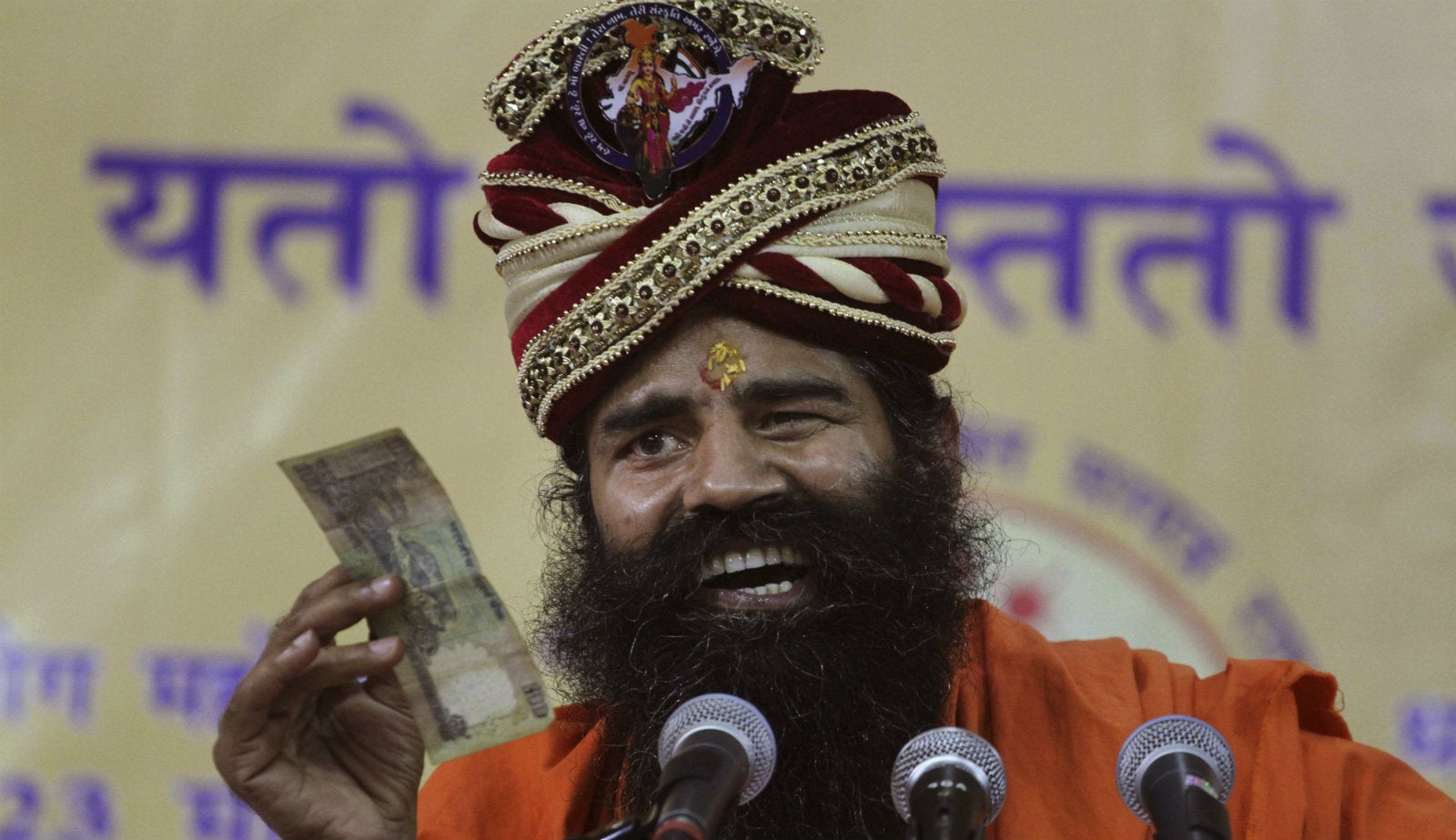

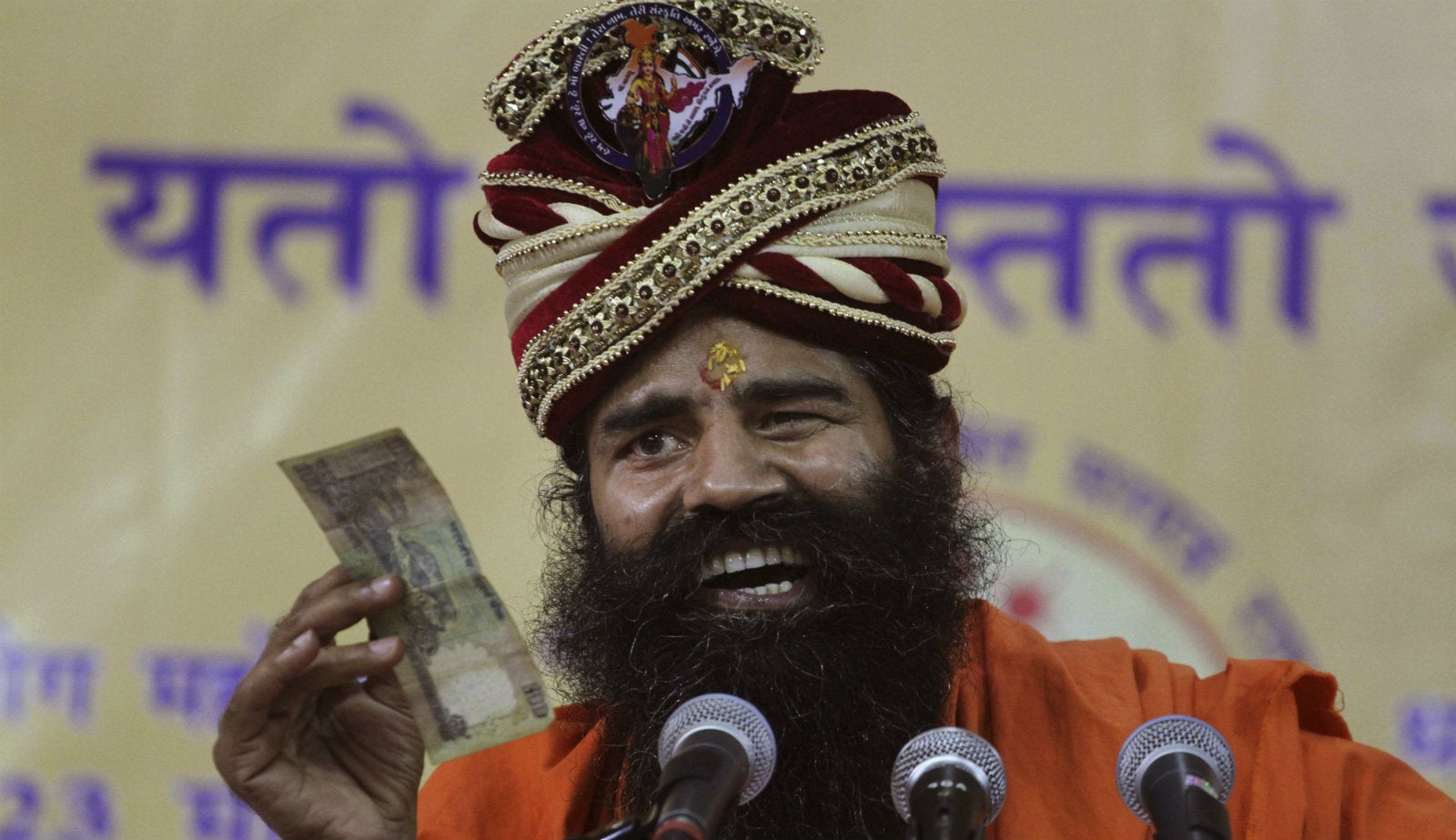

What yoga guru Ramdev can teach the IIM grads at Unilever and Nestle

The news must have come through to you too: Patanjali reported revenues of around Rs5,000 crore ($745 million) for the last financial year — and in doing so went past Colgate in India. Even more interesting is that Colgate is almost eight decades old in India while Baba Ramdev’s brand is barely eight years old.

The news must have come through to you too: Patanjali reported revenues of around Rs5,000 crore ($745 million) for the last financial year — and in doing so went past Colgate in India. Even more interesting is that Colgate is almost eight decades old in India while Baba Ramdev’s brand is barely eight years old.

The saffron-clad Baba’s forecast was quite eye-catching too — he thinks the brand will double revenues to Rs10,000 crores ($1.5 billion) in India by 2017 — which would effectively take them past two other-decades old companies , Nestle and Procter & Gamble (P&G) and leave Patanjali second only to Unilever in India, all in just about 10 years.

So what helped them grow this fast? After all, nobody particularly thought that the Indian fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) scene was ripe for disruption.

Sure, there will be many parts to this answer. Quality products, or at least the promise of these will be one reason. Reasonable pricing will be another. Aggressive distribution will be a third.

But I believe the true innovation is something that was probably done without much thought.

A single brand strategy

The Colgate company sells brands under its name, Palmolive, Ajax and others. P&G goes further — there’s Gillette, Tide, Pampers, Ariel, Duracell and so much more. Unilever is the classic proponent of the multi-brand strategy: from Surf and Dove and Lipton and Lux and Ponds to variants like Surf Excel and Lipton Yellow Label and Lux Supreme and Ponds Dreamflower and far, far beyond.

But take a look at the Patanjali range above — whether it’s toothpaste or rice, noodles or chyavanprash — it’s all under one brand: Patanjali.

Flying in the face of traditional brand theory

Traditional marketing thought has held that one needs to build and nurture a portfolio of brands, each carefully positioned against a separate audience for a separate need.

Perhaps Baba Ramdev wasn’t the first to cock a snook at this dictum. Richard Branson was one of the first to get there, with his “Virgin” brand draped around everything from colas to planes, trains, mobile services and comics.

The thinking is straightforward , if you have heard of my brand and like the personality , then you might be comfortable buying something else I offer. No matter how different the product category.

The modern technology brand playbook

Technology brands like Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and others follow this playbook. The naming formula here is simple: unique brand + generic sub-brand/category name = product brand name.

Google and maps makes for Google Maps. Ditto for Google Search. Or even balloons in the sky — Google Loon.

The word ‘Microsoft’ is a prefix that fits everything from a mouse and keyboard to a windows server. Apple’s generic sub-brands are almost category like: Apple iPod, Apple iPhone, Apple iTunes, Apple iPad and so on.

So what Baba Ramdev is doing is not very different from the new thinking in the business world.

The undoubted benefits of a single-brand strategy

How severe is this problem? Till a few years ago, Nestle marketed over 8,000 brands in 190 countries. Unilever had 1,600 brands across 150 countries and P&G was a bit of laggard with just 250 brands in 160 countries.

But even P&G thought that was a hundred too many, and announced a cull of its brand portfolio down to ‘just’ 150 in 2014.

But in today’s over-branded, over-communicated world, even that may be 149 brands too many. Each brand requires its own marketing and promotional budget, its own brand management team. But cutting it down to one brand makes life so much easier.

You were ready to try Google Maps because you were used to Google Search. You eagerly waited for the Apple iPhone because you love your Apple iMac or were a fan of the Apple iPod.

Every product, in fact, becomes an advertisement for every other product made by the same company. Drastically reducing your required marketing spend by some 80% or more.

So, build just one brand. Let the positive rub-off of that glow on every product you sell under that brand.

Any downsides?

Sure, one could argue that having different brands insulates you if something goes wrong with one.

If Maggi went wrong, it shouldn’t affect Nestle’s other brands.

But it actually did. You know Maggi made for a small share of the company’s revenues — but one hit on one brand’s reputation side-swiped the entire company as you’ll see in this stock price chart:

So what else did Patanjali gain?

It’s harder for a sales guy to go and tell a retailer — listen, please stock Lux and Sunsilk and Dove and Lifebuoy and Close Up. And easier for one to go up to the man and say — hey, just stock Patanjali — and carry our salt and rice and shampoo and soap and what-not. The man believes he is doing you one favour, not five.

So distribution is easier. And that’s a key win.

Consumer recognition is much better too. The lady who goes to the shops says, “Hey, this is that Patanjali stuff. I tried the rice, it was okay. Let me try the shampoo too. It seems to be reasonably priced.” As easy as that.

Of course, the products need to live up to the billing. But in this day and age, that’s not very difficult.

After all, HUL and P&G don’t manufacture their own products — they contract it out to smaller firms. And you can be more than reasonably sure of quality of product in this day and age when you outsource it to someone who makes soaps and shampoos and toothpastes for all the brands.

So what should your brand strategy be?

The fewer brands the better. And ideally, just one brand, please. And don’t get creative with sub-brands. Be as generic and descriptive as you can when it comes to sub-brands or variants.

Don’t make it Lux Supreme if you want to say Lux Extra Creamy. Extra creamy says it better than yet another word for the consumer to remember.

Tesla Model 3 is fine. It’s much better than Toyota Innova Crysta 2.4 GX 7 STR. (Yes, that’s really a name.) How much do you really expect the consumer to remember?

Sony Phone 6.4 tells me it’s probably a good big-screen phone much better than Sony Experia Z Ultra 4G ever will. Yes, that’s really a name too.

Doing one brand well in this over-communicated world is hard enough. Let alone you thinking you have the money and time to establish a second or a twenty-second brand.

And don’t worry too much about traditional thinking on line extensions too. If Google can do maps and going to space under the same brand, I’m sure the consumer will let you do rice and oil and toothpaste under the same name.

She’s already let a non-MBA in orange robes do that. So there’s room for you to follow in those footsteps!

This post first appeared on Medium.