As India celebrates the festival of Ganesh, spare a thought for the 15,000 Asian elephants still in captivity

Nearly one in three Asian elephants live in captivity—about 15,000 in all.

Nearly one in three Asian elephants live in captivity—about 15,000 in all.

The existence of such a large captive population of this endangered, intelligent, and long-living animal poses a number of ethical and practical challenges, but also some opportunities.

Asian elephants, like most land-based megafauna, are endangered and might not survive in the wild beyond the 21st century. As the largest terrestrial animals, elephants are very important for the health of tropical ecosystems—they are like forest gardeners who plant, fertilise and prune trees.

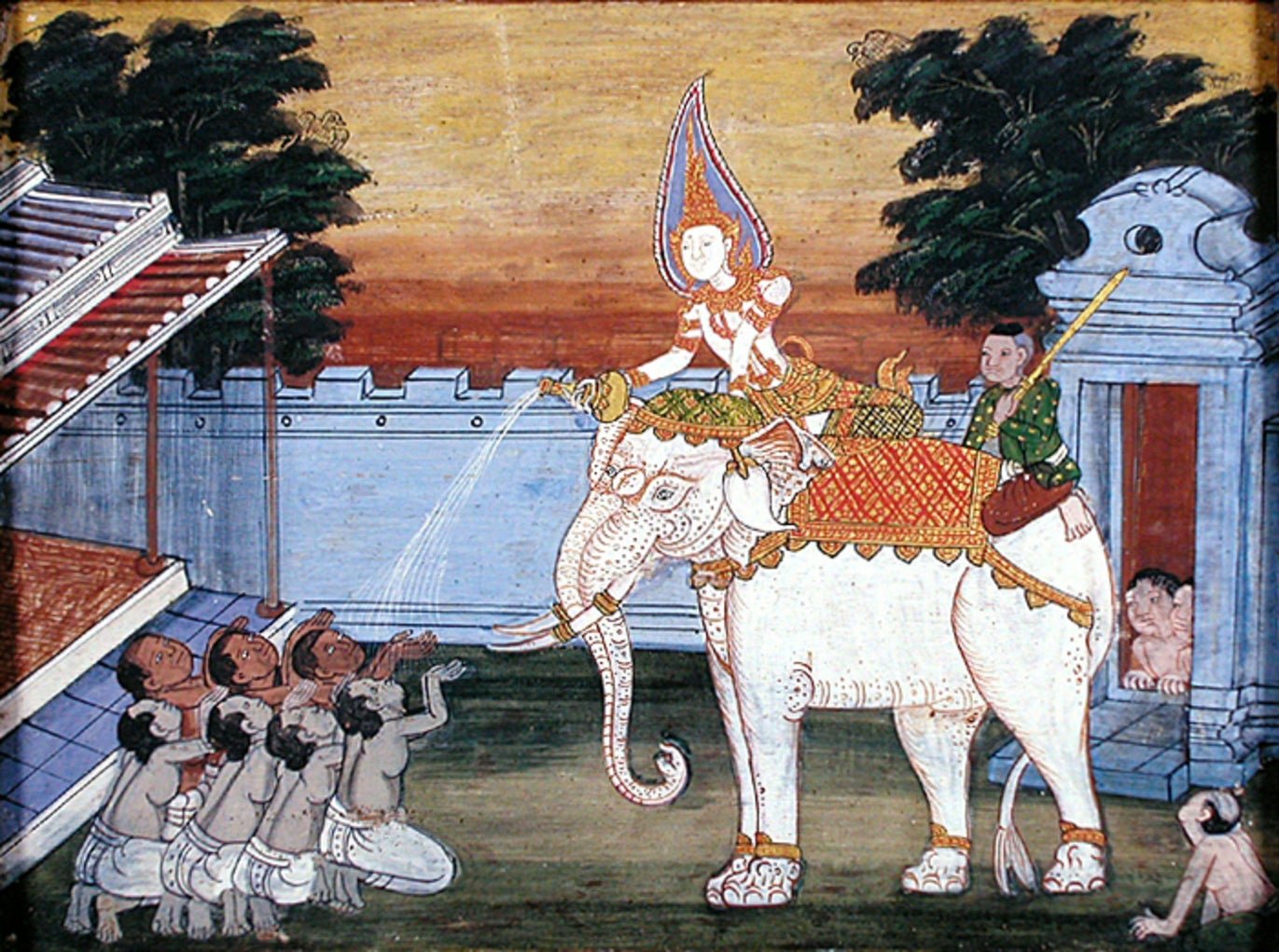

Asian elephants are also remarkable in their cultural significance. They may have been tamed as far back as 6,000 BC, and elephants have since been used for warfare, transport, and as status symbols. They’ve sometimes even been worshipped as deities. Even nowadays, people in countries such as India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand venerate elephants in a way that is difficult for outsiders to understand.

It is because of the cultural significance of Asian elephants that so many of them live in captivity (African elephants can and used to be tamed but, for comparison, only one in 700 currently live in captivity). Unlike dogs, horses, or pigs, elephants are not domestic animals, in the sense that we (humans) do not control their breeding. The large majority of captive elephants were born in the wild and eventually captured and tamed to work for people.

The process of elephant taming is an ancestral tradition that generally involves restraining and punishing until, as one UN report puts it, “the animal’s will is broken”. It’s definitely a painful experience. Contrary to most other mammals, elephants in zoos live shorter lives than in the wild, often suffering from obesity and displaying “stereotypic behaviors” like nodding or body swaying.

Elephants join the tourist trade

Given all the above, is it ethical to keep elephants in captivity?

Well, I’m afraid we have no alternative. All those thousands of tamed elephants in Asia can’t simply be released into the wild. Taming and captivity deeply changes their behaviour. It breaks their social ties and makes them lose their natural fear of people. Released tamed elephants often stay near villages, causing severe conflicts with farmers and exposing themselves to easy retaliation. Humans therefore need to take care of those elephants currently in captivity.

A different question is whether we need to capture any more wild-born elephants. The answer is absolutely no—we need to avoid further live captures to feed the demand of elephants for tourism and entertainment.

With the loss of their traditional “jobs” in forestry and transport, most captive elephants in Asia have joined the ecotourism industry. Watching elephants is a formidable experience that I generally recommend to local and international tourists in Asia.

But this creates another dilemma—is it ethical for tourists to visit elephant sanctuaries? The answer depends on the sanctuary and the activities involved.

Before visiting, I recommend you spend time investigating the available sanctuaries and visiting only those with a good welfare record (and there are quite a few of these). While visiting the sanctuary, be selective in the activities you engage in—avoid riding elephants, for instance, especially on heavy saddles with several other passengers (elephants are strong but their backs still suffer).

You should also avoid noisy shows in which elephants are forced into unnatural behaviour such as silly acrobatics. And most importantly, avoid giving money to people using elephant calves for begging or any other activities that create incentives for further live elephant trade. After visiting the sanctuary, provide (well-mannered and non-patronising) feedback to sanctuary managers, local authorities, and potential future visitors. Good elephant sanctuaries need to be rewarded and bad ones need to feel the pressure to improve.

Tourism doesn’t (necessarily) help conservation

It’s important to emphasise the distinction between elephant welfare and conservation. The latter is a much more difficult challenge. The welfare of captive elephants should not use resources that, otherwise, would be allocated for the conservation of wild populations.

But captive elephants do provide some opportunities here. After all, there are no better ambassadors for elephant conservation than the animals themselves. If properly managed, elephants in sanctuaries and zoos provide a unique opportunity for people to connect emotionally with wildlife, for instance, and learn about how to protect these animals.

The captive population also provides a unique stock to reintroduce elephants in many Asian forests where they have recently become extinct. Elephant reintroductions will be complex and often controversial but—given their ecological importance (remember, the forest gardeners)—they’re something we should seriously start to experiment with.

Unfortunately, we do not have such an opportunity for some of Asia’s other endangered megafauna, such as the Javan and Sumatran rhinos or the Kouprey, a huge ox from Cambodia which is now probably extinct.

Most of the 15,000 Asian elephants in captivity will survive for a few more decades. We need to provide appropriate care for them and make sure we do not remove any additional elephants from the wild to feed the demand for elephant-based tourism. Finally, we can use these elephants for conservation, especially for “rewilding” programs in forests that have lost their elephants.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at [email protected].