Meet the “king” of a forgotten piece of land between India and Pakistan

A guided tour of Ladakh’s Turtuk village, in the mountainous region of Baltistan on the border of Pakistan and India, ended at what is known in these parts as the Royal Palace. After a long walk down narrow and undulating lanes in the crisp afternoon sun, shepherded by a nimble 16-year-old, we had arrived at what was supposed to be the highlight of our excursion. At first glance, it was slightly underwhelming—the house is larger than its neighbours, but little else sets it apart.

A guided tour of Ladakh’s Turtuk village, in the mountainous region of Baltistan on the border of Pakistan and India, ended at what is known in these parts as the Royal Palace. After a long walk down narrow and undulating lanes in the crisp afternoon sun, shepherded by a nimble 16-year-old, we had arrived at what was supposed to be the highlight of our excursion. At first glance, it was slightly underwhelming—the house is larger than its neighbours, but little else sets it apart.

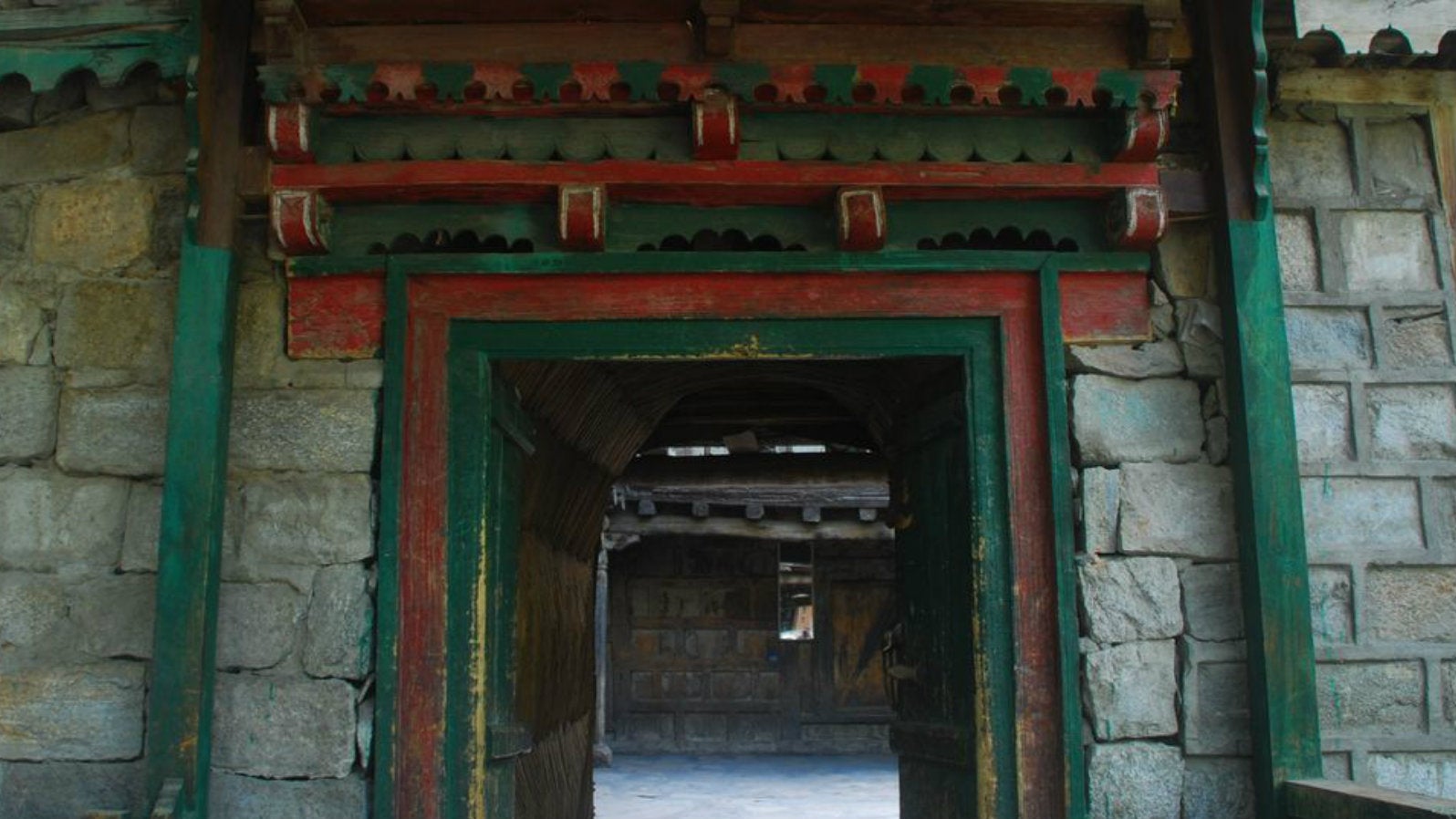

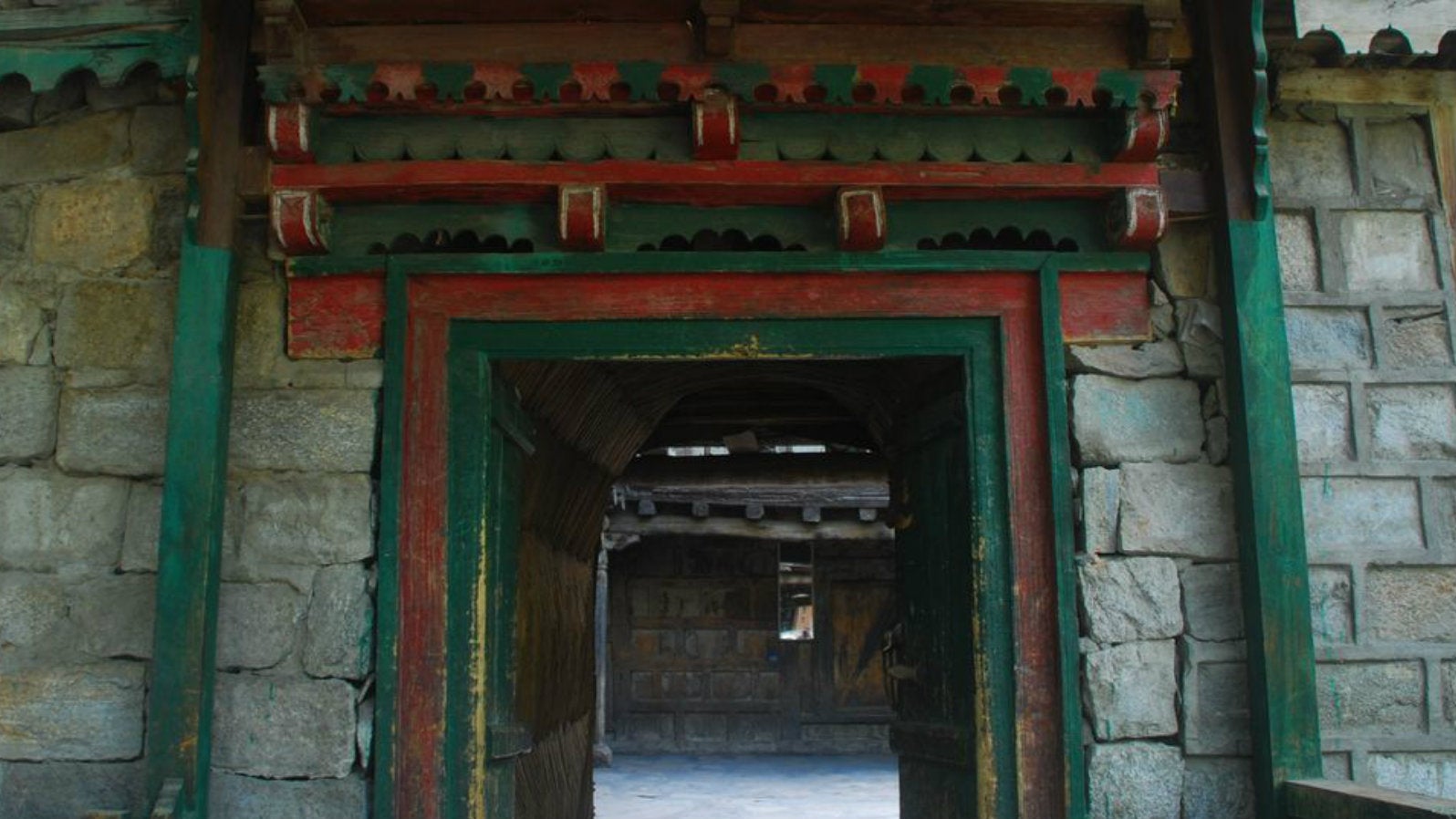

The palace doors opened into a colonnaded courtyard that supported a verandah with no visible access. A short flight of stone steps, which rose steeply through a hidden corner, brought us to a figure supine on a floor mat. Our guide gently nudged the figure and the man stumbled out of his afternoon siesta, disoriented by the sight of so many strangers. He was feeble and slightly bent.

Smoothing the creases on his shirt and patting his disheveled hair into place, he led us into a room, apologising for not according us a better welcome. He explained, somewhat diffidently, that working the fields in the morning sun had induced a mid-day torpor.

He then sat on a couch, but not before picking up a wooden sceptre crested with a distinctive metal serpent head and placing it pointedly on his lap. He then became Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho, the king of Turtuk and the descendant of the Yabgo dynasty of Chorbat-Khaplu, a region that now falls beyond the Line of Control (LOC) in the contested territory of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Though he no longer enjoys the powers or the recognition of a former royal, he is known in these parts as the king.

Across the border

Turtuk is a quaint village perched barely 10 km from the Pakistan border under the benign gaze of the K2 peak. The village, located in the Sheyok river valley about 200 km from Leh, offers verdant relief amidst the spare and stark beauty of Ladakh’s landscape.

Turtuk is in the Indian-administered part of the Baltistan region and borders Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan area.

For years this region was largely forgotten by both the Indian and international media. But over the past month, it has received increasing attention following a public promise made by prime minister Narendra Modi to highlight the plight of the residents of Balochistan and PoK. He first mentioned this in his concluding remarks at the all-party meet on Jammu and Kashmir in New Delhi on Aug. 12 and then again in his Independence Day speech on Aug. 15.

While Balochistan is a province in Pakistan that has been fighting for autonomy, Gilgit-Baltistan is a part of PoK.

The Gilgit-Baltistan territory is special—it is the crucible in which trade, culture, religion, languages, and cuisines from Europe, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and China came together for centuries. India has made many claims over the province and many analysts have recounted its recent political history.

Interestingly, a thin strip of this province juts into India.

The prime minister’s reference to the three disputed areas set off a maelstrom of articles and op-eds (examples are here, here and here) as foreign policy and strategy experts parsed his words.

This prompted me to wonder: what would the people of Turtuk, just a stone’s throw away from Gilgit-Baltistan, make of Modi’s statement? Would they also be deconstructing his speech?

Overnight, a new country

One thing is certain: nationality or sovereignty are elusive if not transient concepts for the king and villagers here. And there’s a good reason for this.

One night in December 1971, village residents went to sleep as Pakistani citizens. They awoke the next morning as Indians. Turtuk, along with three other villages in the vicinity—Tyakshi, Chalunka, and Thang—were occupied by the advancing Indian armed forces during the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war.

Turtuk residents have only one grouse—the Indian Army should have gone a little further and occupied the rest of Baltistan as well. The overnight change of sovereignty split many families along the Line of Control—parents on this side with children and grandparents on the other. Political conspiracies abound on why the Indian Army did not move further afield when it was there for the taking.

Kacho, Turtuk’s king, also has some family on the other side. He traces his lineage to the Ghaz tribe from West Turkestan, today known as Central Asia. His ancestor, Beg Manthal, came to Baltistan in 800 AD from Yarkhand (part of modern-day China’s Xinjiang region) via the Saltoro ridge (west of the Siachen glacier) and conquered Khaplu, in modern-day Gilgit-Baltistan.

The Yabgo dynasty, Manthal onwards, ruled the Chorbat-Khaplu region of Baltistan for a millennium, expanding it over time to Ladakh’s frontiers on one side and to the Ghizer district on the western edge of Gilgit-Baltistan. The dynasty ended in the first half of the 19th century when the Dogra empire, which had in 1846 taken control of Kashmir to form the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, expanded its kingdom to the north and east.

A wall at one end of Kacho’s room has the family tree painted on it, going back centuries. The king said the Indian Army helped him document this. In the face of an elusive administration, the Indian Army means many things to most Baltistan residents—employer and buyer of locally-produced vegetables, milk, fruits and meat, as well as the provider of healthcare and education, and the occasional source of telecom network and other basic infrastructure.

The king describes himself as a writer and said his father didn’t want him to work but instead spread the word about their family. He was not trained in anything but he was made to read a lot. He read books written by local historians and decided that the best thing to do would be to tell his people what they were all about.

But the Indian government banned his book based on complaints from a sect that saw blasphemy in his account of how their religious order was established, he said. He contested the ban in Indian courts and eventually won after years of litigation. But he rues the fact that he didn’t retain a single copy of the book—he doesn’t even remember the name of the Delhi-based publisher.

Connected, yet isolated

Turtuk is a microcosm of Baltistan’s inclusive culture: a multi-ethnic village, with around 4,000 residents speaking different languages and praying to different gods. Different denominations—Nurbakshi Shias, Sufis, Sunnis, Buddhists (and perhaps even Ahmadiyas and Ismaili Shias)—live peacefully, farming and trying to make sense of the burgeoning tourism business. Turtuk was opened up to tourists only in 2010. The chairman of the local school and healthcare committee remarked that many old Turtuk residents had always longed to see cities, but now the cities were coming to see them.

Turtuk was an important junction on the Silk Route with ancient linkages to Tibet, Afghanistan, and the steppes of Central Asia. Today, a part of China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, an attempt to resurrect the Silk Route that connected parts of Asia, Europe, and Africa, will now come close to Turtuk as it proposes to pass through Gilgit-Baltistan.

Turtuk residents fervently wish that the LOC opens up so they can meet families on the other side, re-establish social connections, and perhaps even resume commerce.

The king is still recounting the region’s old linkages when his narrative is cut short by new arrivals, guests of a senior army officer posted in the vicinity. Yabgo Mohammad Khan Kacho apologises and rushes off to attend to the new rulers of Turtuk.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].