In just seven days, this Indian biotech firm can tell cancer patients the ideal course for their treatment

Mallikarjun Sundaram spent much of his childhood traipsing across Tamil Nadu, pulled along by his father’s job in the excise department. Money was tight, so Sundaram, the sixth of seven brothers, had an ordinary schooling at Tamil-medium government institutions in Sivakasi and Madurai. In Class 8, he attended his first English-medium school in Mumbai, where he had moved to in 1983 to live with an elder brother soon after their father’s death. Another tragedy awaited the family.

Mallikarjun Sundaram spent much of his childhood traipsing across Tamil Nadu, pulled along by his father’s job in the excise department. Money was tight, so Sundaram, the sixth of seven brothers, had an ordinary schooling at Tamil-medium government institutions in Sivakasi and Madurai. In Class 8, he attended his first English-medium school in Mumbai, where he had moved to in 1983 to live with an elder brother soon after their father’s death. Another tragedy awaited the family.

In 1986, the youngest of Sundaram’s brothers was diagnosed with cancer; he passed away soon after. “That’s when my awareness of cancer first started,” said Sundaram.

Three decades later, Sundaram is at the cutting-edge of the fight against cancer. Mitra Biotech, a company he helped found in 2010, is pioneering technology that can rapidly test the impact of drugs on a cancer patient by examining a tiny tumour sample in a lab. It means cancer treatment can be personalised to a degree never achieved before, helping physicians and patients pick the most effective drugs while avoiding the cost and side-effects of other medication. Mitra Biotech’s offering has utility in the pharmaceutical industry, too, potentially speeding up the discovery and development of cancer drugs.

The promise of its technology, which the company has trademarked as CANScript, has already attracted some serious money. In late August, it raised $27.4 million from Sequoia India, Sands Capital Ventures, and RA Capital Management. It was the second time that Mitra Biotech had raised funds, after receiving initial Series A financing in 2010 and 2013.

Banaras to Chennai, via MIT

After finishing school in Mumbai, Sundaram entered what was then the Institute of Technology at the Banaras Hindu University, now IIT-BHU, in Varanasi. He spent four years in the holy city by the Ganga reading for a degree in pharmaceutical engineering, before heading to the University of Utah for a PhD in medicinal chemistry. In 1999, he arrived at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a post-doctoral researcher in bioengineering.

Within two years, Sundaram turned entrepreneur. He, along with a bunch of other MIT academics, was a founding scientist at Momenta Pharmaceuticals. The company specialises in the sequencing and engineering of complex sugars for drug development. In 2004, Momenta went public, raising $34.8 million. The same year, as Momenta grew from four founders to 250 employees, Sundaram enrolled at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania for an MBA.

Around this time, Sundaram began a series of conversations with Pradip K Majumder and Shiladitya Sengupta. Majumder is a cancer biologist who previously taught at Harvard Medical School while Sengupta is an assistant professor of medicine at the institution. They are also alumni of New Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

“The idea was kinda vague,” Sundaram said, explaining the results of many rounds of brainstorming. But it broadly revolved around using analytics to improve cancer treatment, and it was enough to excite Sundaram. So, he finished at Wharton in 2006, quit Momenta in 2007, and put together a business plan for their new venture by early 2008. With half-a-million dollars scraped together from friends and family, the trio launched Mitra Life Sciences.

Soon after, Sundaram arrived in Chennai to get down to work, although the precise nature of their product was still evolving. The decision to develop the product in India was driven by a single factor. “We wanted to use all the money to develop the product,” he said. The costs in India were significantly lower, including cheaper access to clinical data, which was critical to the entire project.

It also helped that Sundaram’s father-in-law offered him an 800-square-foot apartment in Chennai rent-free. “The kitchen became the histopathology lab, the bedroom became a cancer biology lab,” Sundaram, 45, recalled. “The other bedroom became the boardroom.”

The company was later reincorporated as Mitra Biotech in 2010, around the time it moved its India headquarters to Bengaluru.

Cancer conundrum

Cancer occurs when the DNA of one of the trillions of cells in the human body undergoes an unusual change. The single cancerous cell then aggressively multiplies, eventually forming a tumour that spreads through the body. No two cancers are the same because their origins and proliferation are varied. That is also why every cancer patient reacts differently to medication.

Apart from surgery to remove tumours, chemotherapy and radiation are the most common treatments for cancer. Although intended only for cancerous cells, chemotherapy and radiation often end up damaging healthy cells, too, resulting in unwanted side-effects. To counter such a situation, a growing stable of precision medication, tailored to target only the cancerous cells, has emerged. To ascertain the combination and dosage of these drugs, however, physicians need better understanding of the specific characteristics of each patient’s cancer. This is where Mitra Biotech’s CANScript promises to revolutionise the treatment process.

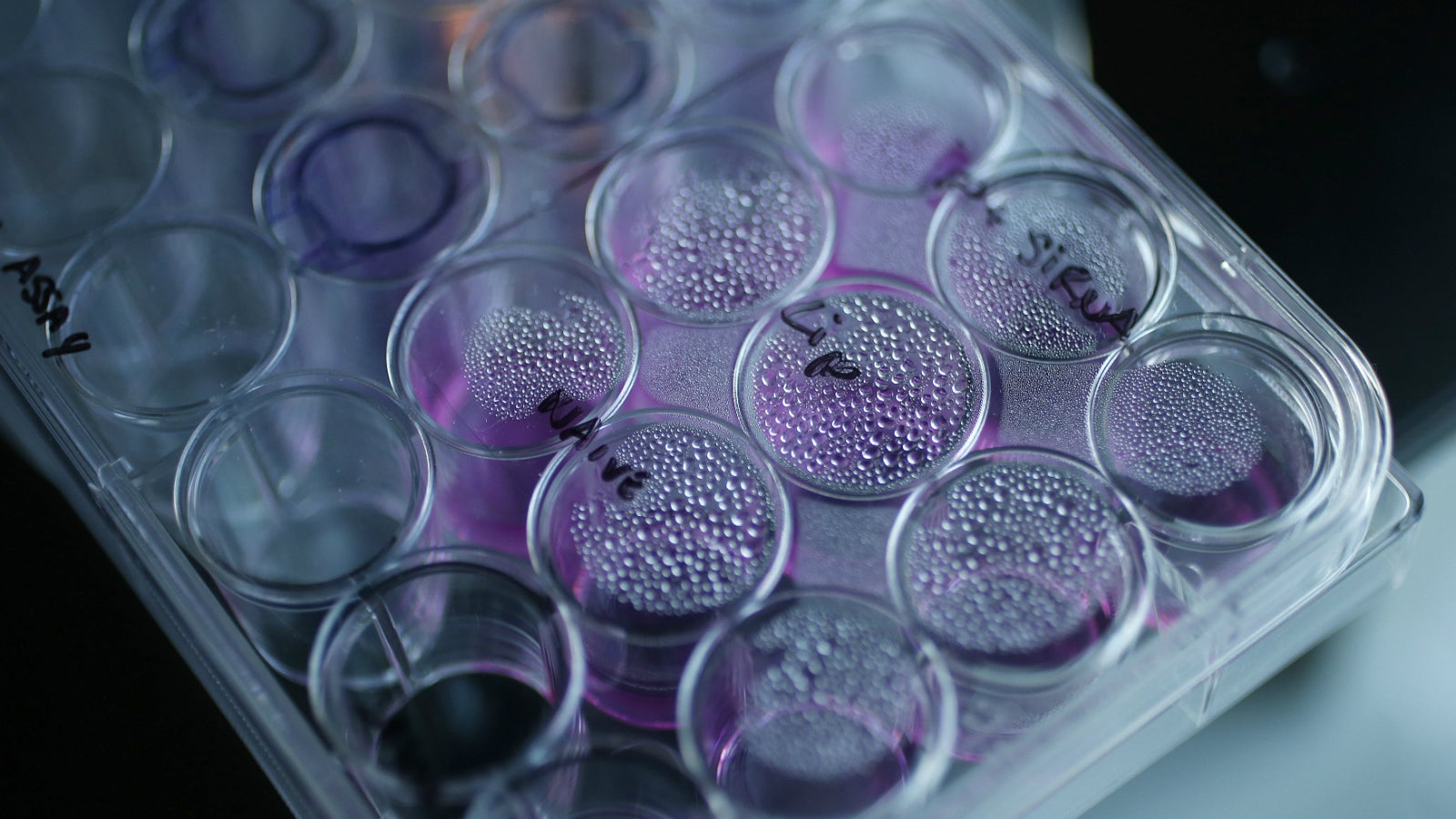

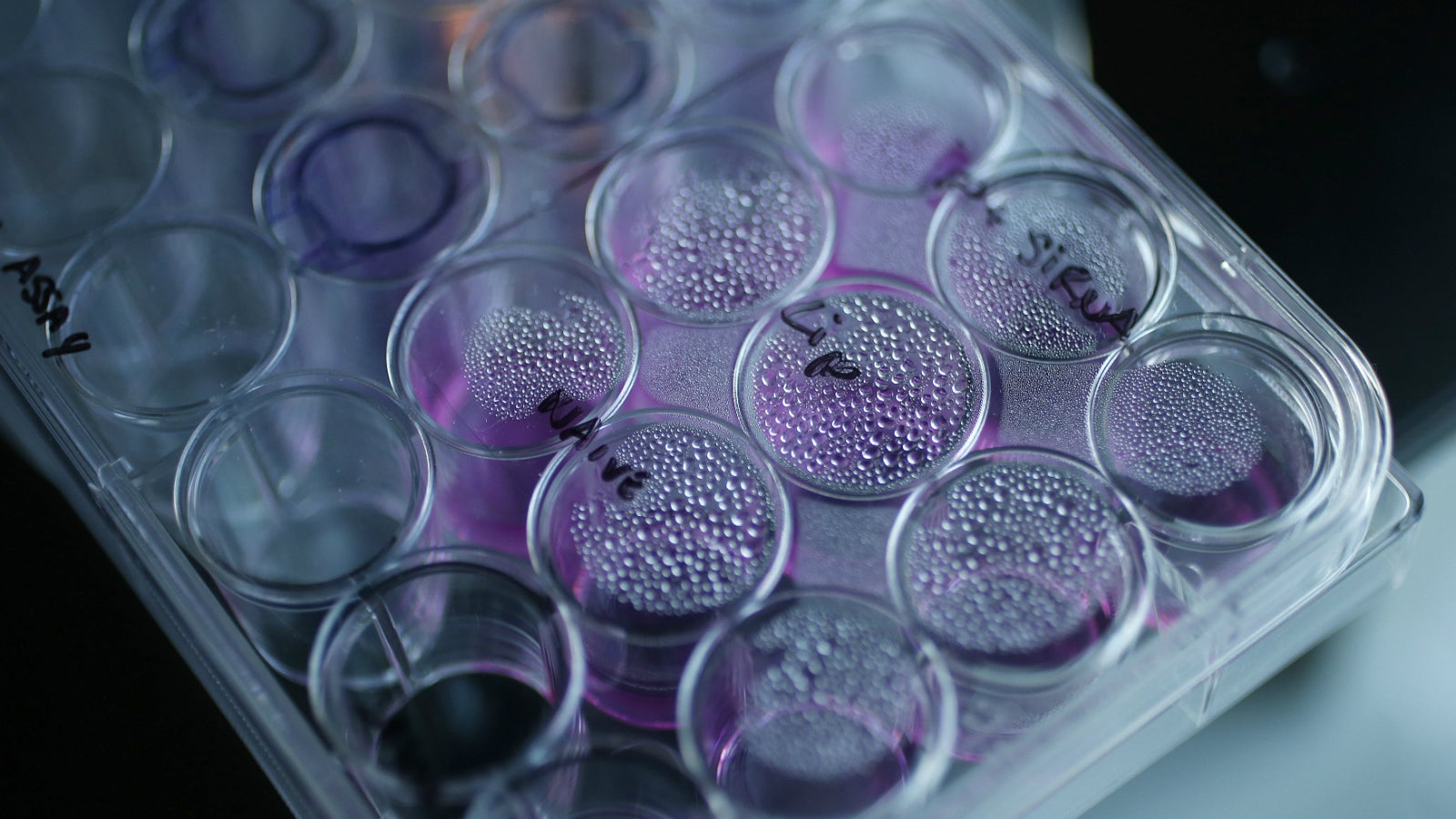

CANScript basically looks to replicate the microenvironment of a cancer tumour on a plate inside a laboratory. For this, the platform requires a tiny sliver of tumour tissue, which can be removed during the biopsy, and 10 millilitres of blood. It then tests out multiple drugs on this laboratory sample, trying to replicate a patient’s reaction to these medications. CANScript then measures many parameters, including tumour cell-death, cell morphology (shape and structure), and rate of tumour growth, to understand the full impact of a particular drug, or a combination of drugs. These are combined into a single numeric score (M-score) that is assigned to a particular drug. “Higher the M-score, the greater the chance of tumour burden reduction,” Sundaram explained.

There are several other technologies that can peer into a single patient’s cancer cells. By investigating the genetic material of cancer cells, scientists can identify the DNA alterations that fuel the growth of a tumour. Such information can be useful for physicians to find a more targeted treatment for a patient. In one out of five breast cancer patients, for example, a protein known as HER2 can result in the proliferation of cancer cells. With drugs that specifically target HER2, the growth of breast cancer cells can be arrested, without damaging healthy cells. But such a genomics-based approach, Sundaram contends, only works in a small percentage of cancer cases.

Then there are also methods like the “human tumour xenograft,” where cancerous tumour cells from a human patient are transplanted into mice. It’s a process that Mitra Biotech experimented with—and discarded—in their early days working out of the small Chennai apartment. “All tumours don’t grow in mice,” Sundaram said. “Maybe one out of 10 will grow.” Even when they grow, it can take up to three months for any conclusive data to be obtained. It is also tough to find the right mice in India, so Mitra Biotech had to import theirs, adding to the cost.

In comparison, Sundaram argued, CANScript delivers results within seven days, can test multiple drugs, and is relatively affordable at about $600 or Rs 40,000 per examination in India.

In a February 2015 paper in Nature Communications, a peer-reviewed scientific journal, Mitra Biotech published the results of testing CANScript’s model for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer. The study first recreated the microenvironment of 109 patients suffering from one of the cancers, tested the response of a set of drugs on the tumours and then used the data from this set to shape a predictive model. This model was then tested on a group of 55 patients with one of the cancers and treated with the same drugs as the earlier study. In this test, CANScript essentially correctly predicted each cancer patient’s response to the treatment.

“We are also dedicated to demonstrate clinical utility of the system in different cancers, different class of drugs through additional clinical studies that will continue along with the commercial launch of the product,” Sundaram said, adding that these studies would be conducted in multiple geographies, including the US, Europe, and India.

These are still early days, but Mitra Biotech is already working with a handful of hospitals in Bengaluru and New Delhi, Sundaram said.

Great ambitions

Yet, it isn’t only cancer diagnostics that Mitra Biotech is targeting. CANScript also has application in the pharmaceutical industry, with major drug companies, governments, and philanthropists pouring massive sums of money into finding new medication that can beat cancer.

The platform’s ability to test multiple drug combinations quickly and relatively cheaply is among the reasons why Mitra Biotech, which operates out of Boston and Bengaluru, thinks it has a shot at owning a corner of the $100-billion global oncology market. “All the major pharma companies (globally) have started working with us,” Sundaram asserted, without divulging any names.

The company’s aim, though, is much bigger and, as Sundaram explained, relatively straightforward: to become the global leader in cancer therapy selection. It may seem a tad too ambitious for a startup that traces its foundation to a nondescript Chennai apartment with five employees.

But Mitra Biotech, with a solid pedigree, a product at the cutting-edge of medical science, a global footprint, and $27-million in funding as of late August, is hardly your usual company.