Why India’s plan to go cashless remains a distant dream

At the end of a panel at the “Startup India Standup India” event, adequately named “Disruptive Power of Technology in Financial Inclusion,” the panelists, which included Paytm CEO Vijay Shekhar Sharma, Eko founder and CEO Abhishek Sinha, and Ispirt’s Sharad Sharma, pledged to make India a cashless economy.

At the end of a panel at the “Startup India Standup India” event, adequately named “Disruptive Power of Technology in Financial Inclusion,” the panelists, which included Paytm CEO Vijay Shekhar Sharma, Eko founder and CEO Abhishek Sinha, and Ispirt’s Sharad Sharma, pledged to make India a cashless economy.

That was Jan. 16, 2016 and nearly 10 months later, prime minister Narendra Modi disrupted the financial payments space with his move to remove (and gradually recycle) 86% of the cash in the Indian economy.

The government’s narrative surrounding demonetisation has changed frequently since then: first it was an attack on black money, then about addressing the funding of terrorism. But the latest pitch, for a move that reportedly has caused several deaths, is that it moves India towards a cashless economy, what Venkaiah Naidu, the union minister for urban development and information and broadcasting, also referred to as a “Cultural Revolution,” entailing a “behavioural modification.”

But how prepared are we to go cashless? How affordable is it for people to go cashless?

Our contention here is that there is no parity between cash and digital money: a rupee paid in cash is far more convenient for a user and is less costly compared to a cashless system.

Infrastructure issues

Number of citizens on mobile: Not all Indians use mobiles and not everyone is connected. The latest figures from the Indian telecom regulator TRAI show that, as of July 31, 2016, (pdf) India had a tele-density of 83%, with Bihar, Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh reporting a tele-density of less than 70%. While state-wise data for wireless tele-density is not available, it wouldn’t be very different, since most connections in India are wireless.

Note that these are the number of connections, not users, so you will have to discount this significantly, because many users have multiple SIM cards. The proof: Delhi has a tele-density of 234.77%. Urban wireless tele-density is 148%, and rural is 50.72%. And of the 1,034.23 million connections, 88.88% are active.

So do we have enough people with mobile connections in India? Not close to a billion, especially in rural India.

Number of mobile users who are connected to the internet: There were 342.65 million internet connections by the end of March, of which 20.44 million were wired connections. In total, 149.75 million were on broadband (3G + 4G + wireline broadband) and 192.9 million on “narrowband.” The narrowband internet subscriber base was 192.90 million (2G and wireline broadband). Click here for statewise broadband and narrowband data.

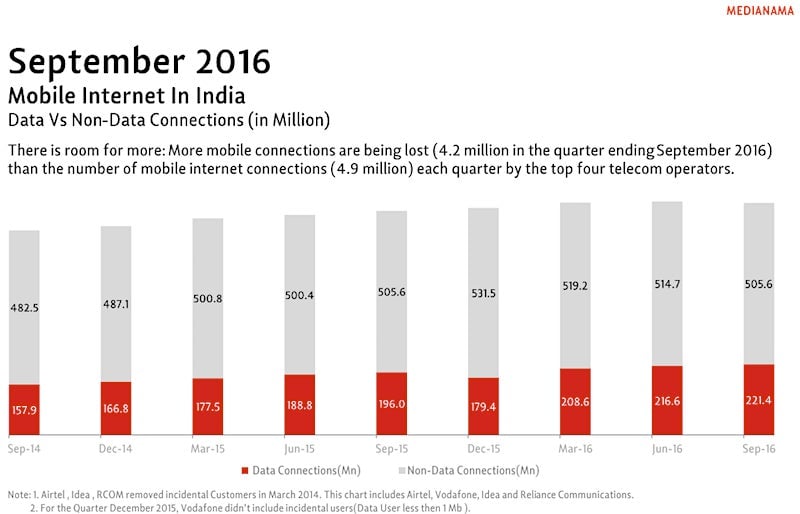

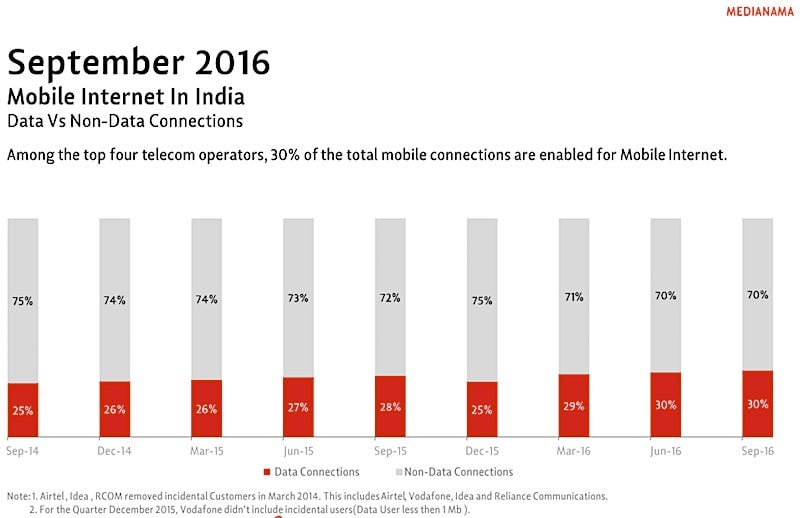

For the top four telecom operators, the number of mobile connections that are data-enabled (usage of more than 1mb, or more than 10mb per month, depending on the operator) is around 30%.

How many people are online daily? These are connections. How many are online monthly? According to Facebook India managing director Umang Bedi, 165 million users log on to Facebook on a monthly basis. How many go online daily? Only the telecom operators know.

Availability of reliable connectivity: “When we were doing Aadhaar,” TRAI chairman RS Sharma said at an event in October, “and we said it will be an online infrastructure and identity. People said you are creating an online identity in a situation where connectivity doesn’t exist. So there was a huge amount of pressure on us to make it work offline as well. Our view was that we are creating a future-proof identity infrastructure. We don’t want an infrastructure which becomes useless tomorrow. The future is online. The future is a connected world.”

But the future isn’t now, and Sharma knows that: “Today with Aadhaar,” he added, “I keep getting complaints that there isn’t a tower in a place and therefore we weren’t able to authenticate. Therefore, connectivity is a very very serious problem.”

If you drive from one place to another, especially beyond the national highways, along state highways, through pot-holed and dusty roads connecting villages and towns, to small places in the hills, you’ll find connectivity sparse and fleeting. A month ago, I had to drive 15km to find a spot where there was sufficient connectivity to respond to a message. Pangot in Uttarakhand, where I was staying, has a post-office, but barely functional data from Idea, and none from Airtel, BSNL or Jio.

The fact is that in cities we’re spoiled by the connectivity we get, and we really shouldn’t judge the quality of connectivity by what high ARPU urban, concentrated areas get. Let’s also not forget the connectivity issues in cities, typified by call drops (though these have reduced now).

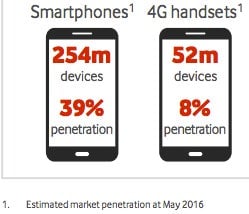

Availability of user devices: According to Idea Cellular CEO Himanshu Kapania, there are currently over a billion mobile phones in India, of which around 850 million are feature/smartphones and 150 million LTE-enabled phones.

Vodafone’s smartphone estimate:

Airtel India managing director and CEO Gopal Vittal recently said, “What we have found is that people with smartphones, not all of them use data. That number of people with a smartphone using data is probably around 60% to 70%. And the new smartphones that are coming are not necessarily the smartphones that people are naturally using data (on)… one of the big jobs for us is to actually get all of those smartphone devices to also consume data.”

This is important because most payments businesses don’t support feature phones, and while we will see smartphone penetration grow, we need feature phone support for now. Mobikwik has promised it, apart from rolling out a low-bandwidth application.

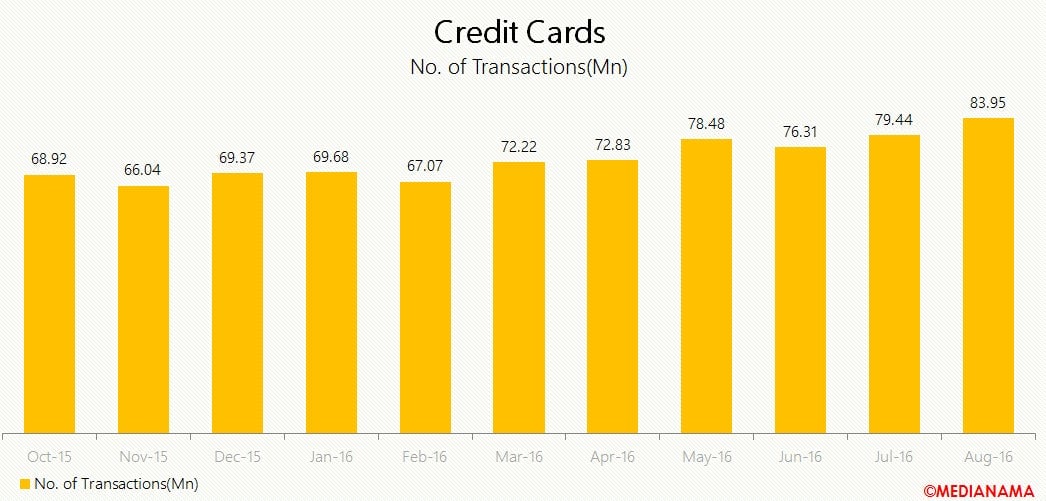

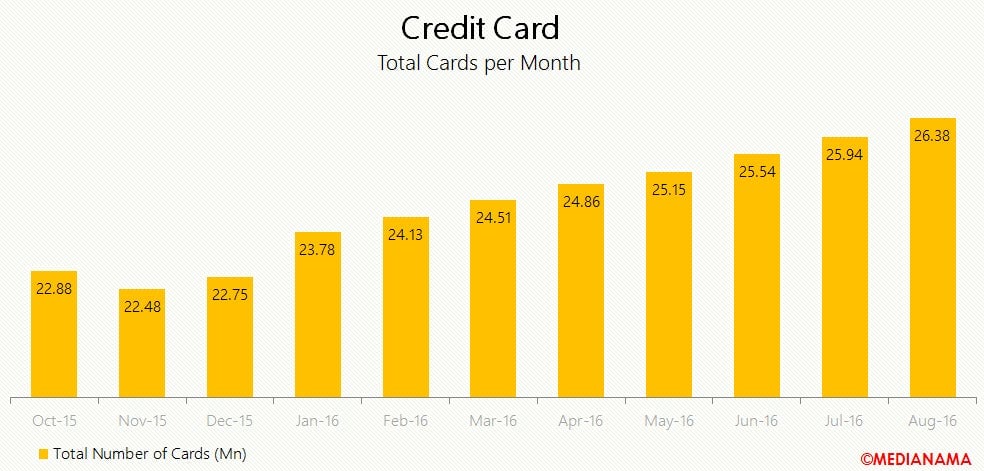

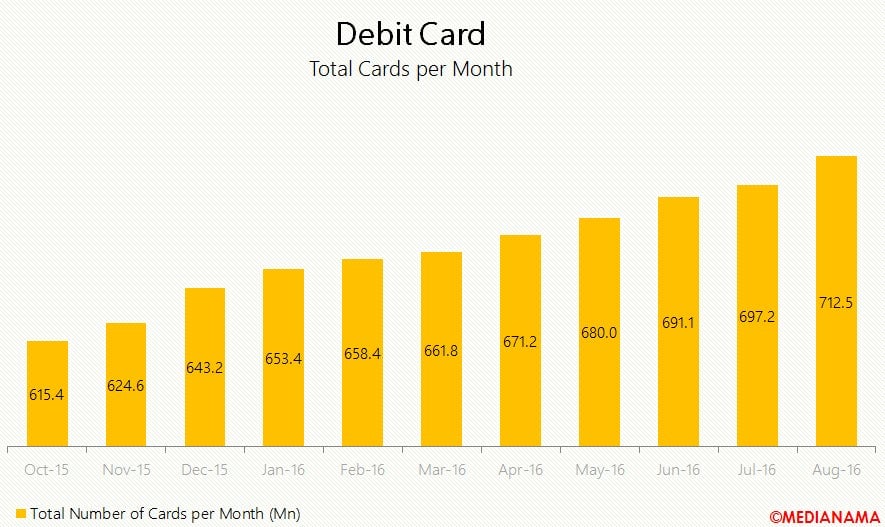

Merchant acceptance: India had 712.5 million debit cards, and 130.53 million transactions, as of August 2016. That’s around 18 transactions for every 100 cards. As for credit cards, there were only 26.38 million in India as of August 2016, accounting for 83.95 million transactions.

Demonetisation might lend itself to a greater utilisation of cards but there were only 1,461,672 point of sales (PoS) machines in India, as of August 2016, according to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

In all likelihood, these are concentrated in major cities, with some merchants having more than one machine as backup. A 2015 Ernst and Young report said that India has the dubious honour of having one of the lowest PoS terminal penetration, with only 693 machines per million people. Brazil has 32,995 terminals per million people and China and Russia both had around 4,000 terminals per million people.

Payment and mobile network capacity: What we’ve seen with demonetisation and the increase in usage of cards and online payments is that somewhere in the value chain, banks and/or payment gateways were not in a position to handle the load. Transactions failed and we were told that Visa wasn’t able to handle the load.

At present, there isn’t sufficient capacity to accommodate escalated usage if everyone starts transacting digitally. More importantly, do we have the network capacity to deal with this? What happens in an emergency situation, when networks are down because everyone is trying to call everyone, as we’ve seen previously in India? If you don’t have cash, and there is insufficient connectivity, how will you be able to buy anything or use public transportation, for instance.

Usage issues

Time taken for a transaction: If you’ve driven through a toll booth, or paid for parking, you know that operators keep exact change because they expect to receive notes of specific denominations. The time taken isn’t usually to tender change but for printing a receipt.

Observe a small shop selling high-frequency purchases like mobile recharge cards, candies or cigarettes and you’ll see that the pace at which they close a transaction with a customer is critical for them. They don’t typically give a bill for each transaction, and that’s a problem when it comes to taxation. But from a user’s perspective, think of the additional time a billed transaction takes :

- For a card, you need to place it in a PoS machine, get the user to punch in a PIN, and—if there is connectivity—wait for the merchant to get a confirmation before you can leave.

- For digital transactions, you need to get the user to scan a merchant QR code and authenticate with a PIN (ideally). Or, you need the merchant to send a payment link to the customer, for him or her to receive it, open a page, type in details, and then complete the transaction. Then the customer has to wait for the merchant to receive a confirmation of the transaction before he or she can leave. Can you imagine doing this while exiting a parking lot or at a toll booth? If you’re buying a Rs2 Pulse candy, imagine the friction involved, as indicated here. The quickest means of payment is an NFC machine, but most phones aren’t NFC-enabled in India, nor do many merchants accept NFC payments.

Security issues: The weakest security link in any transaction is not the technology system but the user and a lack of understanding of security issues. For instance, to withdraw money from ATMs, some people were giving others their card and PIN numbers (for example: this and this). But there are other risks, too. In 2011, it was believed that payment gateway CC Avenue was hacked. HDFC Bank, too. And just last month, HDFC and Axis Bank were hacked.

The difference between depending on cash and digital payments is that using cash limits the damage from losing a note or a number of notes. When it comes to digital transactions, the risks are higher.

This of course doesn’t mean that digital shouldn’t be an option—I’m not saying that—but it shouldn’t necessarily be the only option. It also doesn’t mean that storing all your cash in your house is risk-free, but the move to make India a cashless country increases security risks for all citizens, with each account/e-wallet company becoming a single point of failure.

No privacy for the cashless: A switch to living cash-free means that each and every transaction is tracked and documented. This is great for governance but there is no protection for citizens with regard to who owns that data, whom they can share it with, and how it will be utilised.

If I’m using an e-wallet, where is the law that prevents the usage of that data for advertising? By switching to cash-free transactions, you’re not giving users a choice. India doesn’t have a privacy and data protection law and, shamefully enough, the Indian government has gone to court arguing that there isn’t a fundamental right to privacy in the country. To quote the Attorney General of India, speaking in August last year, “Violation of privacy doesn’t mean anything because privacy is not a guaranteed right.”

Cash offers that relative privacy and anonymity that the Indian government is trying to deny its citizens. The only cashless currency that affords anonymity is bitcoin.

Update: We’ve done an analysis of what kind of sensitive data e-wallet apps are collecting.

Language compatibility: Paytm has recently updated its application with some features enabled in Indian languages. Mobikwik has done English and Hindi. PhonePe works in English, Hindi and Tamil. However, most mobile handsets don’t have an Indian language interface and that’s the case for most mobile apps and services, too. Ola is available in Indian languages only for drivers, not passengers. Apart from Snapdeal, no e-commerce company has tried going the Indian language way. There’s a part of the population in India which still isn’t able to read and write, let alone read and write English. The digital divide here is massive and that’s why physical notes worked.

Interoperability issues (between payment systems): Cash is interchangeable. You don’t need an internet connection, a mobile app or a bank account. But now you have a situation where State Bank of India (SBI) doesn’t allow payments into a Paytm wallet via netbanking and even e-wallet to e-wallet transfer isn’t allowed. There’s the Unified Payments Interface, set up by the bank owned group NPCI, where the RBI has not allowed e-wallet to e-wallet transfers.

Merchant costs: Merchants need a working internet connection to accept digital payments. They also need to pay a monthly cost to rent a machine or own a smartphone with an application to accept payments. On credit cards, merchants are charged a merchant discount rate (MDR), an inter-bank exchange fee, of 1.7%-2.5% per transaction. On debit cards, they need to pay 0.75% per transaction below Rs2,000 and 1% for transactions above Rs2,000. For UPI, merchants are charged 0.75% per transaction plus other costs (on par with debit cards).

Customer costs: You need a smartphone and an internet connection, plus you’ll need to pay USSD charges (Rs0.5 per session) and data charges when applicable.

So where are we today?

Using cash isn’t the same as using digital payments because:

- Not enough people have mobile connections or internet connections, and the internet isn’t prepared to accommodate a massive surge in use at times of emergency. What’s more, many don’t use the internet regularly and smartphones and mobile apps that support all Indian languages aren’t available. Internet connectivity isn’t reliable, available or as cheap for users as cash.

- The process of making digital payments in India is not easy and it’s time consuming.

- Making digital payments costs more for both the merchant and the customer.

- Digital payments can lead to major security risks and currently there aren’t adequate processes in place to address issues among either merchants or customers. Above all, not enough is being done to educate the consumer, the weakest link in the chain.

- Digital payments aren’t a single standard like cash: money in one type of account is not the same as in another type of account, and it is not interoperable, unlike cash.

Here’s the thing: cash might be more expensive for the government, because of tax evasion, corruption, the need to keep recirculating old, spoiled currency, and the cost of enabling transfers, but digital is very expensive for citizens. What is happening here is a transfer of the cost of money from the government to citizens, as well as a massive collection of data.

But does that mean that there shouldn’t be any cashless transactions?

Certainly not. The point is that we’re not ready yet. Many of the issues mentioned above will be addressed one by one: connectivity will (hopefully) improve; Indian language interfaces and operating systems should be developed, security and customer care can also be improved and smartphone prices will come down. But the idea to force people into adopting cashless payments is foolish and unnecessary when you don’t have the wherewithal to meet the demand at that scale so quickly. People are hurting, and there are no means of meeting the high demand in the near term.

The important thing is to give people choice, and switch people to living cash-free gradually.

Parity between cash and digital money is probably impossible to achieve, but there are means of getting closer to it by creating an incentive structure for that switch. That involves making cash more expensive than going cash-free, and ensuring better enforcement.

This post first appeared on Medianama.com. We welcome your comments at [email protected].