British universities moulded great Indian minds like Gandhi and Ramanujan, but that tradition may end soon

With recent reports that the UK’s Home Office is considering cutting the number of international student visas issued annually by nearly half, it’s clear that the government is keen to stick to its promise of reducing the inflow of foreign students.

With recent reports that the UK’s Home Office is considering cutting the number of international student visas issued annually by nearly half, it’s clear that the government is keen to stick to its promise of reducing the inflow of foreign students.

In her speech at the Conservative Party conference earlier this year, the home secretary, Amber Rudd, revealed government’s plan to create “two-tier visa rules” in a bid to limit the number of international students coming to study in the UK, which would affect “poorer-quality universities and courses.”

Then there was Theresa May’s recent trip to India which was dominated by the row over visas. This was in part because May, as home secretary, had introduced tighter immigration rules—halving the number of Indian students in Britain.

Indian prime minister Narendra Modi expressed his country’s dissatisfaction saying that if Britain wanted post-Brexit trade, it needed to reciprocate by opening its doors to India’s youth. Ever since, Indian newspapers have tracked how visa regulations are making the UK a less attractive option for Indian students.

For British universities seeking closer ties with Indian partners, the government’s stance and recent announcement are unfathomable, and have been condemned by many university vice-chancellors. This is because not only do Indian students have a long tradition here in the UK, but also because it sends out a message completely opposite to the one universities are trying to promote: welcoming international students.

Historical ties

Indian students first came to study in Britain in the 1840s. They were Christian converts attending theological colleges or young Bengalis completing medical training. At first, only a handful arrived each year, but from the 1870s, the numbers began to swell.

Most came to study law or medicine or to prepare for the Indian civil service exams. The majority were Hindus from Bengal or Bombay, but there was also a disproportionate number of Muslims, Parsis, and Christians. By the interwar years, as many as 1,800 Indian students were in the UK at any point.

Most of them were attracted by the prestige associated with degrees or qualifications awarded in Britain and, as long as Britain maintained its vast empire, its universities and institutes were considered the pinnacle of postgraduate education.

Some professions in India were not even open to applicants without a British qualification. For example, between 1853 and 1922, it was only possible to appear for the examinations for the Indian civil service in Britain. Similarly, to be an advocate in Indian courts during the Raj (with the right to defend or prosecute criminal cases) required a call to the Bar in Britain.

Student support

Of course, the large numbers of Indian students in imperial Britain required adequate support. And the India Office in London took responsibility for receiving and settling newly-arrived students via a philanthropic organisation called the National Indian Association. Founded in 1870, its aim was to spread knowledge of India in Britain and foster friendly relations between Indians and Britons.

Young students were invited to attend its lectures, social gatherings, and sightseeing tours. At these events, they mixed freely and forged friendships with British college students, wardens, and professors, as well as former colonial officers and earlier Indian migrants.

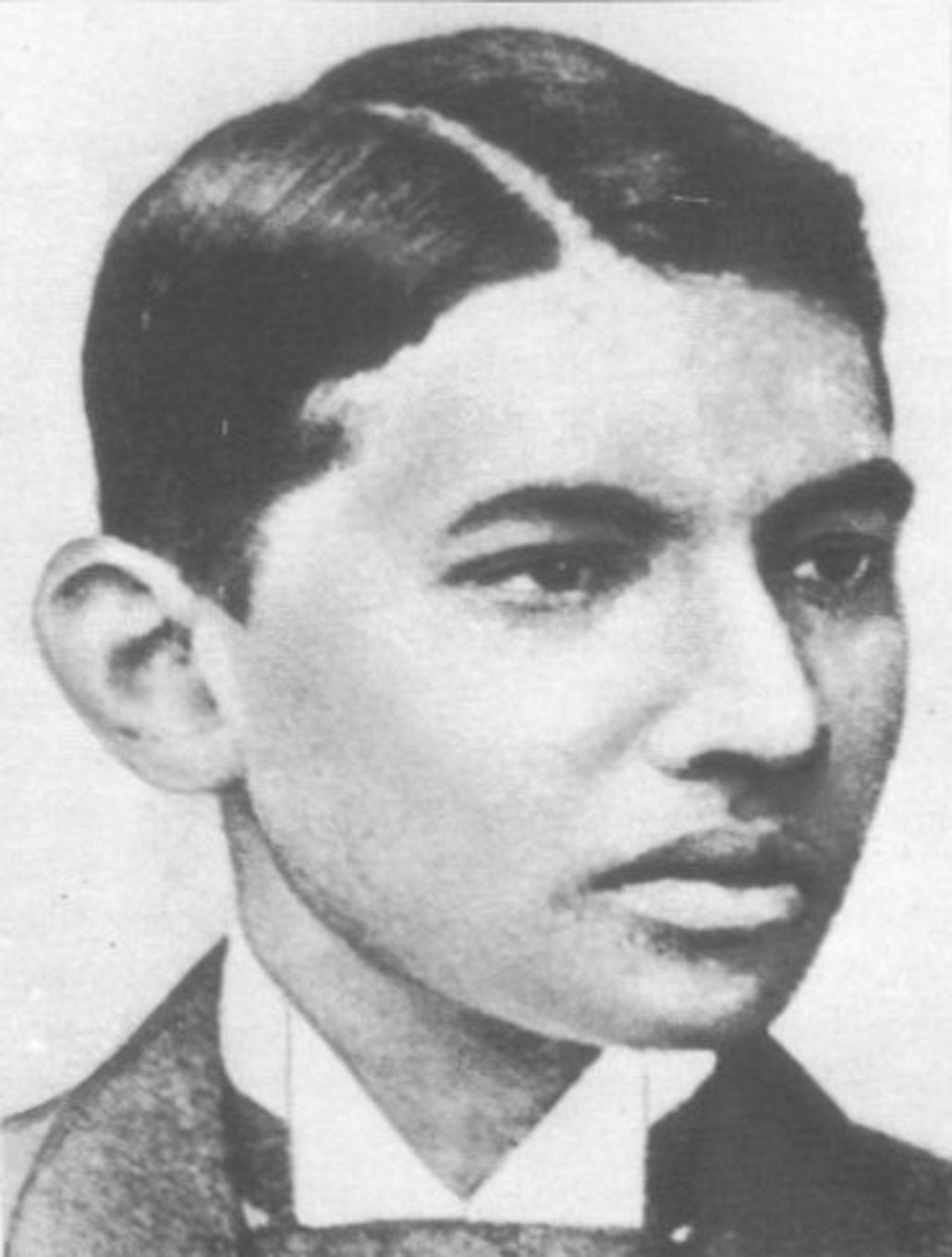

Some of the most famous Indians in recent history were students in Britain. Best known is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who spent three years at the Inner Temple in London from 1888 preparing to be a barrister.

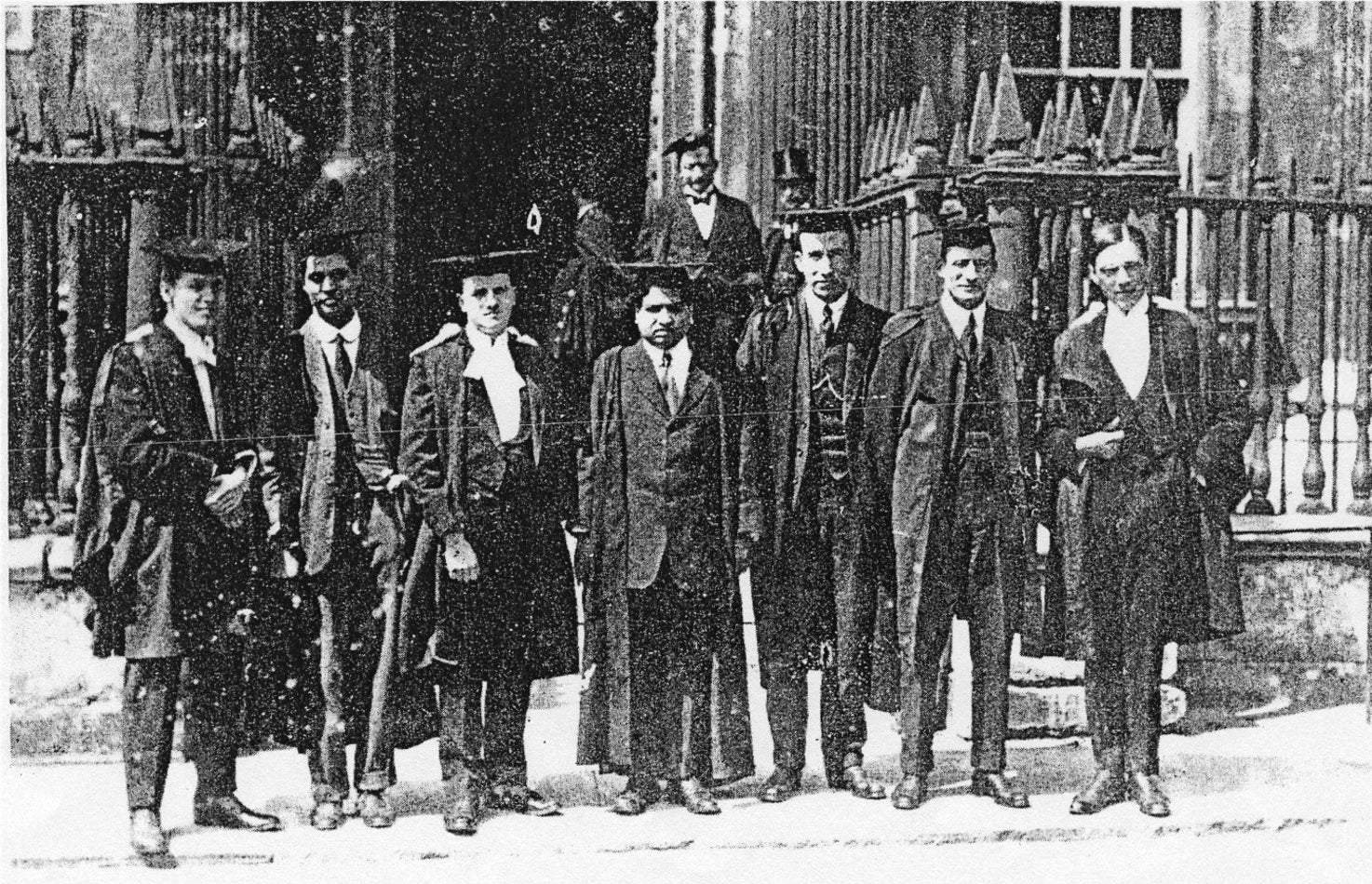

Srinavasa Ramanujan was also a student in Britain. During World War I, he studied theoretical maths at Trinity College, Cambridge. A recent biopic, The Man Who Knew Infinity, highlighted his struggle with racial bigotry, English food, and ill-health due to the cold and damp climate—even though he flourished intellectually. Sadly, his experience echoed that of many students from colonial India.

As the author Atiya Fyzee wrote while training to be a teacher at Maria Grey College in London in 1907: Other Indian students in imperial Britain may have been less well-known, but that doesn’t make them any less important to our history—including the sizeable number of women who came from India to study in the UK.

“Whichever educational institution I go to, I always find some or other Indian girl.” Her own studies were funded by a scholarship from the colonial government directed at women teachers.

Because female students were considered more of a curiosity than their male counterparts, they appear to have received a warmer reception from the British public. After studying at Leeds University in the 1930s, Iqbalunnisa Hussain recorded the generous hospitality offered by professors, her fellow students and members of the local community.

Writing history

A great deal is known about Indian students in the colonial period from their own writings. Highly literate and articulate, they wrote letters, diaries, speeches, and memoirs that described their impressions and experiences—and these original sources have drawn the attention of many historians.

Indian students have been drawn to study in Britain since the colonial period. And if we forfeit that legacy now, our universities and our communities will be all the poorer for it. But they are also relevant to the current debate over visas for overseas students. This is because they point to the overwhelming benefits—as well as the challenges—of welcoming international students to British universities. They can also help us understand how those challenges may be overcome.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at [email protected].