Welcome to an emerging Asia: India and China stop feigning friendship while Russia plays all sides

After a few timid signs of warming, Sino-Indian relations seem to be headed for the freezer. While Beijing refuses to take Indian security concerns seriously, New Delhi may have decided to take the Chinese challenge head-on. To complicate matters for India, its erstwhile ally Russia, which has become a close friend of China, is showing interest in establishing closer ties with Pakistan.

After a few timid signs of warming, Sino-Indian relations seem to be headed for the freezer. While Beijing refuses to take Indian security concerns seriously, New Delhi may have decided to take the Chinese challenge head-on. To complicate matters for India, its erstwhile ally Russia, which has become a close friend of China, is showing interest in establishing closer ties with Pakistan.

The latest move that clenches teeth in India is China refusing to lift a hold on Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammad chief Masood Azhar, accused of plotting multiple acts of terrorism against India, and blocking him in December from being listed as a terrorist by the United Nations. Since March, China has blocked India’s attempts to put a ban on Azhar, under the sanctions committee of the UN Security Council, despite support from other members of the 15-nation body. In response, India has gone beyond expressing dismay by testing its long-range ballistic missiles—Agni IV and Agni V—in recent weeks. Pakistan, aided by China, has also jumped in by testing its first sea cruise missile that could be eventually launched from a Pakistani submarine.

China has upped the ante, indicating a willingness to help Pakistan increase the range of its nuclear missiles. China’s official mouthpiece, Global Times, contended in an editorial: “if the Western countries accept India as a nuclear country and are indifferent to the nuclear race between India and Pakistan, China will not stand out and stick rigidly to those nuclear rules as necessary. At this time, Pakistan should have those privileges in nuclear development that India has.”

China’s $46 billion investment in the so-called China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC, also troubles India as the land corridor extends through the contested territory in Kashmir which India claims as its own. India views CPEC as an insidious attempt by China to create new realities on the ground and a brazen breach of India’s sovereignty and territory. The Chinese media have suggested that India should join CPEC to “boost its export and slash its trade deficit with China” and “the northern part of India bordering Pakistan and Jammu & Kashmir will gain more economic growth momentum.” New Delhi has questioned if China would accept an identical situation in Tibet or Taiwan, or if this is a new phase in Chinese policy with China accepting Pakistan’s claims as opposed to the previous stance of viewing Kashmir as disputed territory.

Faced with an intransigent China, India under the centre-right government led by Narendra Modi is busy reevaluating its China policy. Modi’s initial outreach to China soon after coming to office in May 2014 failed to produce any substantive outcome and he has since decided to take a more hard-nosed approach. New Delhi has strengthened partnerships with like-minded countries, including the United States, Japan, Australia, and Vietnam. India has bolstered its capabilities along the troubled border with China and the Indian military is operationally gearing up for a two-front war. India is also ramping up its nuclear and conventional deterrence against China by testing long-range missiles, raising a mountain strike corps for the border with China, enhancing submarine capabilities, and basing its first squadron of French-made Rafale fighter jets near that border.

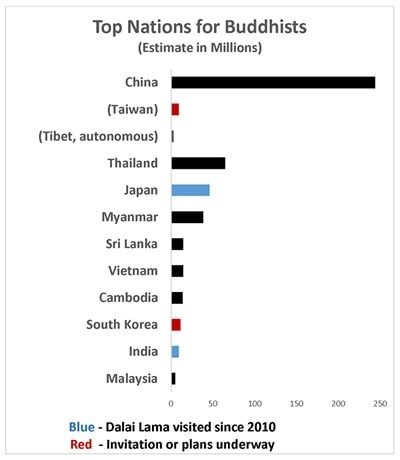

More interesting is a significant shift in India’s Tibet policy with the Modi government deciding to bring the issue back into the Sino-Indian bilateral equation. India will openly welcome the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader who has lived in exile in India since 1959, at an international conference on Buddhism to be held in Rajgir-Nalanda, Bihar, in March. And ignoring Beijing’s protests, the Dalai Lama will also visit the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh which China claims as part of its own territory.

After initially ceding ground to Chinese sensitivities on Tibet and refusing to explicitly acknowledge official interactions with the Dalai Lama, a more public role for the monk is now presented as an essential part of the Indian response to China. In the first meeting in decades between a serving Indian head of state and the Dalai Lama, Indian President Pranab Mukherjee hosted the Buddhist leader at the inaugural session of the first Laureates and Leaders for Children Summit, held at the president’s official residence in New Delhi in December.

China has not taken kindly to these moves by India and vehemently opposes any attempt to boost the image or credibility of the Dalai Lama.

China has been relentless in seeking isolation for the Dalai Lama and often succeeds in bullying weaker states to bar the monk. After the Dalai Lama’s November visit to the predominantly Buddhist Mongolia, where he is revered as a spiritual leader, the nation incurred China’s wrath and soon apologised, promising that the Dalai Lama would no longer be allowed to enter the country.

But India is not Mongolia. There is growing disenchantment with Chinese behaviour in New Delhi. Appeasing China by sacrificing the interests of the Tibetan people has not yielded any benefits for India, nor has there been tranquility in the Himalayas in recent decades. As China’s aggressiveness has grown, Indian policymakers are no longer content to play by rules set by China. Although India has formally acknowledged Tibet as a part of China, there is a new push to support the legitimate rights of the Tibetan people so as to negotiate with China from a position of strength.

This Sino-Indian geopolitical jostling is also being shaped by the broader shift in global and regional strategic equations. Delhi long took Russian support for granted. Yet, much to India’s discomfiture, China has found a new ally in Russia which is keen to side with it, even as a junior partner, to scuttle western interests. Historically sound Indo-Russian ties have become a casualty of this trend and to garner Chinese support for its anti-West posturing, Russia has refrained from supporting Indian positions.

Worried about India’s growing proximity to the United States, Russia is also warming up to Pakistan. The two held their first joint military exercise in September and their first bilateral consultation on regional issues in December. After officially lifting an arms embargo against Pakistan in 2014, Russia will deliver four Russian-made Mi-35M attack helicopters in 2017 to Pakistan’s military. It is also likely that the China-backed CPEC might be merged with the Russia-backed Eurasian Economic Union. Jettisoning its traditional antipathy to the Taliban, Russia indicates a readiness to negotiate with the Taliban against the backdrop of the growing threat of the Islamic State in Afghanistan. Towards that end, Russia is already working with China and Pakistan, thereby marginalising India in the regional process.

As the Trump administration takes office in Washington on Jan. 20, it will be rushing into headwinds generated by growing Sino-Indian tensions and a budding Sino-Russian entente. Trump’s own pro-Russia and anti-China inclinations could further complicate geopolitical alignments in Asia. Growing tension in the Indian subcontinent promises to add to the volatility.

This piece first appeared on YaleGlobal Online. We welcome your comments at [email protected].