As Myanmar goes after the Rohingya, the world must ensure this minority’s safety and dignity

Violence against the Rohingyas, an ethnic Muslim minority in Myanmar, has reached a new high according to a report published by the United Nations.

Violence against the Rohingyas, an ethnic Muslim minority in Myanmar, has reached a new high according to a report published by the United Nations.

Its release followed an investigation that took place on the Bangladeshi border with Myanmar in January, after the UN Human Rights Office team was denied access to the worst-affected areas of northern Rakhine State in Myanmar. Horrific testimonies of brutal killings of adults and children, including babies, as well as gang-rapes and disappearances have been detailed in the document.

Concern about Muslim minorities has been rising in this country since U Ko Ni, a prominent human rights lawyer close to Aung Saan Suu Kyi’s party, and a Muslim, was shot dead on Jan. 29.

As of February 2014, there were 1.33 million Rohingyas in Myanmar, and more than one million living overseas. They are mainly in Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, India and Pakistan.

At least 87,000 Rohingyas have been displaced since the military launched a crackdown in western Rakhine state in early October 2016.

In Myanmar, most Rohingyas have been stripped of citizenship, and face serious violations of human rights including restriction of freedom of movement, marriage restriction, exclusion from education and health care, enforced birth control, arbitrary taxation and forced labour.

Rohingyas need to apply for travel pass to even visit a neighbouring village and are required to obtain permission for marriage by paying high fees and bribes which can take several years to get. Worse, they are beaten, tortured, killed and raped; their houses are burnt, and the survivors are forced to leave ancestral home for an uncertain future. It’s no surprise the Rohingyas are often called the most persecuted people on earth.

Several academic studies have established that the persecution on the Rohingyas amounts to genocide. But the Myanmar government keeps denying these claims.

Why are Rohingyas forced out of Myanmar?

The government actually denies the existence of any ethnic group named “Rohingya.” It often considers this group to be “Bengali”, formed of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite the fact that Rohingya have lived in the Rakhine State for generations.

Under the 1982 Citizenship Law of Myanmar, the government created three classes of citizens: full, associate and naturalised, and subsequently provided colour-coded “scrutiny cards”. Pink cards were provided to full citizens, blue for associate citizens and green for naturalised. Most of Rohingyas were not provided a card at all. They are rather considered “Myanmar residents”, which means neither citizen nor foreigner.

In 1993, Rohingyas were given “white cards” which allowed them to vote. However, these cards were revoked because of protests by Buddhist nationalist and monks. This meant Rohingyas could not vote in the landmark 2015 general election, which paved the way for Aung San Suu Kyi and her party to come to power.

Many candidates, even sitting MPs, from Rohingya and other Muslim groups were banned from participating by all major political parties and the election commission.

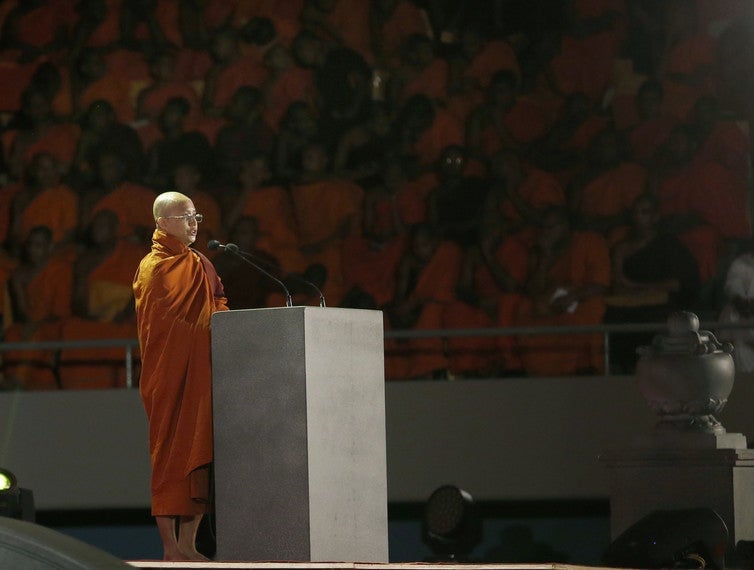

Discrimination and violence against Rohingyas mainly lie in a false fear of Muslim power generated by Buddhist nationalists led by radical monks under the 969 movement and Ma Ba Tha (the Organisation for the Protection of Race and Religion).

Although Buddhist monks are usually portrayed as peace-preachers globally, many in Myanmar are involved in political activism. Ashin Wirathu, the charismatic leader of some of these radical movements, often called “Burmese bin Laden”, openly spreads anti-Muslim rumours and hatred.

No one dares to challenge Wirathu in fear of retaliation, and major political parties have designed policies considering the likely reaction from Ma Ba Tha. Therefore, not only stateless Rohingyas but also non-Rohingya Muslim groups with Burmese citizenship such as the Kaman people, as well as Muslims in Meiktila and Mandalay, have all faced religious violence. Yanghee Lee, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights for Myanmar was herself labelled as a “whore” by Wirathu when she advocated for human rights of Rohingya in 2015.

The radical monks have drafted and successfully pressured the Myanmar government to pass so-called Race and Religion Protection laws such as Religious Conversion Law, Interfaith Marriage Law and Population Control Law that largely target Muslims.

Although the Ma Ba Tha has become weaker in recent months following a dispute with the Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein, state councillor Aung San Suu Kyi and her party do not dare to challenge the already strong public sentiment against Muslims.

The celebrated transition to democracy in Myanmar has only increased populist pressure and majoritarian autocracy, ironically shutting up the voices of previously active human rights advocates.

Bangladesh’s defensive position

Dealing with the waves of Rohingya refugees has always been a dilemma for the bordering host community and the government of Bangladesh. Recently the government has even proposed to relocated the Rohingyas on a flood prone island off the Bangladesh coast.

While there is a desire to help the refugees on humanitarian and religious grounds for Rohingyas, which I witnessed during my fieldwork, population pressure and security concerns have put the government in a defensive position.

In 1978, during a major influx of Rohingyas, Bangladesh hosted approximately 222,000 refugees who were mostly repatriated soon after. In 1991-92, another major flow of around 250,000 refugees entered Bangladesh. They have been repatriated, except for about 32,000 who are still staying in two registered camps in Cox’s Bazar district in Chittagong.

However, many Rohingyas, including some repatriated ones, continued to cross the porous borders into Bangladesh. These post-1992 arrivals have not been registered officially, and they are living in unregistered camps and along with local communities near the border areas. The similarity in religion and language (Rohingya and Chittagonian dialect are largely similar) has allowed some to become informally integrated into the South-Eastern areas of Bangladesh.

During the fresh arrivals in 2012 after a communal riot in the Rakhine State, the government of Bangladesh took a tougher stance; border guards refused entry to the refugees, pushing them back to Myanmar. This violates the principle of non-refoulment, which prohibits the return of refugees to persecution.

Since last October, the government has refused to offer any asylum to the refugees. Prime minister Sheikh Hasina told the Bangladeshi parliament, “We cannot just open our doors to people coming in waves”.

Political pressure

The government’s position can be explained by increasing economic growth of Bangladesh and subsequently less dependence on international aid. This has allowed the government to brush aside international diplomatic pressure. But Bangladesh is far from alone in trying to avoid responsibility amid a global refugee crisis.

Still, many refugees do manage to enter Bangladeshi territory. According to a UN estimate, 66,000 new refugees have taken shelter in Bangladesh in recent months. Before this, as per 2015, the number of unregistered Rohingyas in Bangladesh was estimated to be between 200,000 and 500,000.

Recent government actions seem to follow the directions of a strategy paper designed in 2014. Based on its recommendations, the government has conducted the first-ever census to count “undocumented Myanmar nationals” in Bangladesh. The census result has not been made public so far.

Rohingya policy is also dictated by diplomatic relations with Myanmar. The current government of Bangladesh has shown its serious willingness to improve relations with its neighbour. Dhaka wants to eventually repatriate Rohingyas to Myanmar, but it is happy to increase engagement on other issues such as business in the meantime.

Bangladesh is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol and does not have any national legislation to deal with the refugees.

In the absence of any legal standard, a former UN representative in Bangladesh notes, the refugees are administered through an “ad hoc, arbitrary and discretionary system”. Although some Rohingyas have found a safer place to stay in Bangladesh, they are still suffering from fear and insecurity.

According to the Foreigners Act 1946 of Bangladesh, the large number of unregistered Rohingyas are considered “illegal foreigners.” Police may arrest them anytime if they wish. Though the police rarely do that, the possibility of arrest and indefinite detention keeps them in constant fear.

They are also not allowed to seek employment, register marriage, move freely and get higher education. Many of them live in overcrowded, unhygienic makeshift camps. In 2010, Physicians for Human Rights reported that the camps are like an “open air prison”.

The solution starts with Myanmar

The Rohingya crisis is, first of all, a political issue in Myanmar. The ultimate solution lies in the granting citizenship and ensuring equal rights in their ancestral home.

Unfortunately, the United Nations and influential states have done nothing more than criticise. For powerful neighbours such as India or China, but also for many global players, Myanmar is an untapped resource and investment hub waiting to be explored. It has become evident that the humanitarian intervention is reserved for strategic and business usefulness, not to protect the most vulnerable.

Until a permanent solution is found in Myanmar, it is the responsibility of refugee hosting countries, including Bangladesh, to ensure that Rohingya people can live with basic human rights and dignity. Rather than making administrative interventions, granting proper legal standards would serve both refugees and the national interest of Bangladesh.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.