Life lessons from growing up in an Indian joint family, stealing grandpa’s ciggies and mangoes

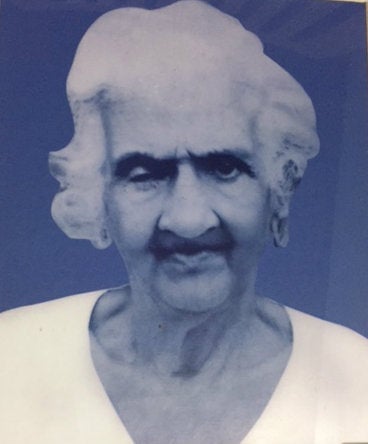

Meenakshi Amma was 87 when she died in 1986. She was my great-great grandmother on my mother’s side.

Meenakshi Amma was 87 when she died in 1986. She was my great-great grandmother on my mother’s side.

The only memory of the matriarch I have is of a lady in a white mundu (loincloth) and ill-fitting blouse, sitting all day long at the doorstep, legs stretched forward. Her hair white and short and face furrowed, she incessantly ground her toothless jaws against each other. With failing eyes, she seemed to keep vigil on the cowshed in the front yard where Lakshmi and its calf were tethered.

Like the flies bothering Lakshmi, who, too, was constantly ruminating, we, the hollering kids, would swarm around Meenakshi Amma. But she remained stoically silent and rarely moved, even when threatened with being photographed.

Nothing mattered to her. The British Raj, the grandeur of the local king’s court, the bloody Maplah rebellion of 1921, decades of freedom struggle, Mahatma Gandhi, the communist movement, India’s independence, the Emergency of 1975-77—she had seen it all.

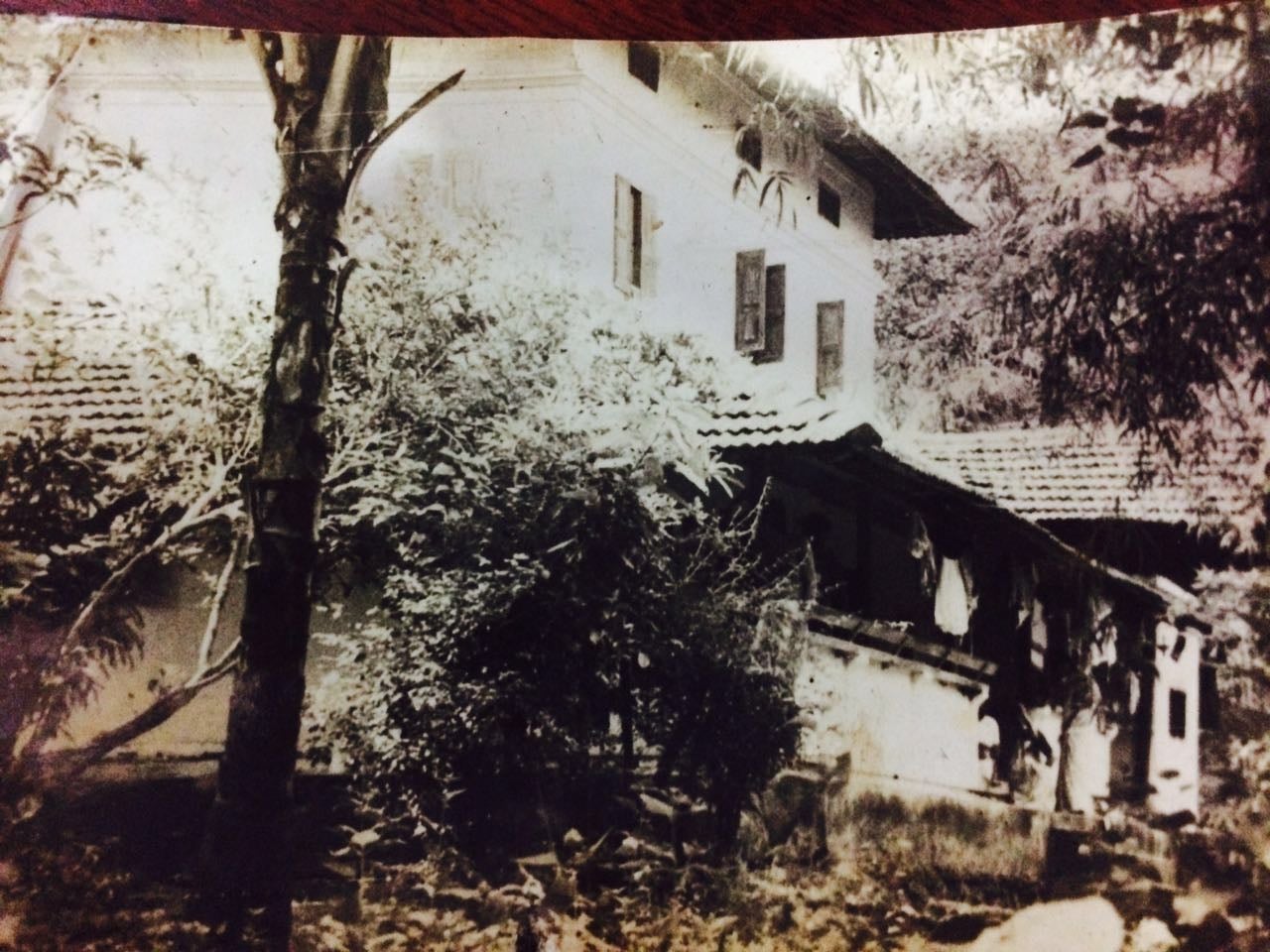

Within this single-frame memory of an ancestor rest my notions of home, family, and relationships. To me, Meenakshi Amma is where history begins. And Pullara, my ancestral home in Kerala, is the geography of that history.

Innumerable sons, daughters, uncles, aunts, grandmas, grandpas, brothers & sisters-in-law, cousins—second, third, and even fourth—followed her and lived together and died under its roof. Some just left home and disappeared forever. Others seem like eternal beings, always around. In its open and pillared verandah, legions have got drunk, quarrelled, got drunk again, and made up. Most made love, some just fucked, a few never even bothered to copulate. A good number of them thrived, some wasted away. A few saw financial ruin, a handful rose again, heroically. Some never stepped out of the household’s ever shrinking property. Others travelled the world.

Pullara. We are that endangered species of the Indian society: a joint family. In a nation obsessing over everything nuclear, we are the quintessential museum piece.

Many have been the criticisms against our kind, some of them irrefutable. Yes, joint families can limit individual ambitions. Yes, they abet unemployment. And they are far from being the ideal basic units to efficiently organise the society.

But with the right nurturing, a joint family can foster an exhilarating spirit of camaraderie and oneness. With strong leadership, it can provide critical social and financial safety. Most importantly, it can guarantee emotional anchoring, priceless and vital in a dramatically changing world of ours.

“I’ll just go home”

“Tara! Home. I’ll go home, and I’ll think of some way to get him back! After all, tomorrow is another day!” When drained of the last bit of doggedness and cunning, Scarlett O’Hara always knew where to recharge.

Most of us do. We always have mom and dad. Or siblings. Some of us lean on grandparents. Or friends. We invest a lot of emotional wealth in these relationship banks. But banks can close down, too. Death, the burning of bridges, or just plain fatigue can deny us critical support just when needed.

I was 11 and my sister six in 1991 when we lost our father in Bangalore. Relatives on his side never mattered anyway.

Enter, the joint family. Or as it happened, we entered Pullara as full-time legatees of its madness, affection, lethargy, and quirks.

With my sister and I in safe hands, mom quickly eased into battle mode and went abroad to earn a living, visiting us only every two years. The first few months of her absence were wrenching. And then the slow recovery began as a whole host of others filled the gaps brilliantly, consciously, and, if I may add, selflessly.

Grandpa pampered and turned my sister into a spoilt brat. Annoyed with this bias, grandma took me under her wing with a vengeance. My uncles, of mercurial tempers and creative temperaments, hand-held us through life skills: buying groceries, managing bank accounts, motorcycling, guest-management, and even enjoying alcohol, responsibly.

Outside, we made friends among boys and girls in the neighbourhood, but that was incidental. My best friend was from within the family, among the eight resident kids and assortment of visiting cousins. Our furtive childhood pleasures ranged from chocolates stolen from the fridge to hundreds of cashew fruits gathered from nearby groves. We flicked grandpa’s beedis (Indian cigarettes) and tiptoed into the backyard during lazy afternoons, with only the friendly-neighbourhood mongoose, the mother hen, and her chicks catching us in the act.

When it came to matters of the heart—and many there were—it was my mom’s younger sister that I confided in. Of course, mom got to know, but usually not first. So, even today, if I must vent against someone without inflicting damage, it is her that I call. If ever there was an agony aunt.

In short, there are many I could turn to during emotional disarray. As my generation matures, and the elderly either slow down or fade away, I know that someone from or at Pullara is always just a phone call away. I’ll just go home.

Everybody’s a migrant

As a media student in Pune in early 2002, I found an eatery near college, offering fairly clean, edible, and affordable stuff. Once during lunch, a classmate casually mentioned that he missed eating beef and the restaurant manager promised to make us some. Another classmate sitting next to him promptly rose, visibly alarmed, and was never seen again at that joint.

I was amused at such a reaction, because where I came from, beef was a popular meat. Though many elders at home still avoid it, those who eat it aren’t shunned. In fact, no food—fish, mutton, chicken, duck, squid, crab, beef, veal, prawns, pork, pigeon, civet, tortoise, frog, rabbit, or quail—is taboo. Some of these are not prepared at home because none knows how to. So we usually head for the local toddy shop.

And no, drinking is not prohibited either. Like most of Kerala, we love our sundowners, and often top it up with some music.

Every Pullara generation is primed to be itself, without being tied to anachronistic traditions or orthodoxies. Grandpa was a radical Leftist, but his lady cousin was a virtual consort of the neighbourhood deities till she died. An uncle is as reserved and calm as a seer; a six-footer cousin is as garrulous as a politician. Yeah, we are chalk, cheese, apples, and oranges living in a trinket box.

Because, in more ways than one, we are all migrants or travelers.

While nobody today knows when the house itself was built or who built it, legend has it that in the early 19th century, the Zamorin king of Malabar invited one of our ancestors to Kozhikode from Ponnani, a traditionally Muslim-dominated town, 70km south. Ever since at least, the regular infusion of a variety of genes has enriched us. In the late 19th century, a Telugu-speaking bureaucrat married into the family. My father was a Tamilian. Meenakshi Amma’s son, a Royal Indian Navy sailor, frolicked in the world’s harbour towns before retiring at the end of World War II. Part of Pullara, led by my grandpa, lived in Bangalore for decades beginning in the 1960s, with a few years of Jodhpur and Barrackpore thrown in between. Many of us speak Kannada and Tamil, Bangalore’s dominant languages, better than Kerala’s Malayalam. Mom speaks fluent Bengali. In recent years, we’ve had an Uttar Pradesh native and one more of Tamil Nadu married into the clan.

If you haven’t heard of the Sanskrit term vasudhaiva kutumbakam, “the world family,” now you know what it feels like. At least in miniature.

Today, when we settle down for meals to celebrate Onam, Eid, Christmas or other family events, risque jokes flying thick and fast, this is what Pullara looks like: The teetotaler vegetarian sitting next to the tipsy auto-driver, the insurance agent perched between the unemployed invalid and the former air force personnel, the top corporate executive exchanging health tips with the young engineer, the hotel management grad discussing movie-making with the journalist, the incorrigible communist debating with the pious, the philanderer ribbing the chronic bachelor, the fashionista disputing the feminist’s views, the artist trying to take the puerile along. Besides, the yummies on the plantain leaf, there is almost always a serving of affection, bluster, candour, and devotion.

Rarely do personality types, cuisines or cultures intimidate us Pullarites. For we are everybody’s people.

Who’s in charge?

In the summer of 1999, I left Kozhikode to attend college in Bangalore. By then, we were reduced to 18 people at home. The finances, the discipline, the safety of the children and the aged, hospitalisations, family functions, deaths, and births—all these were to be managed. My uncle, a pharmaceutical executive, was in charge.

A severely short-tempered man of steely resolve—and just 36 in 1999—he deployed all his managerial, leadership, and emotional skills. One moment he would be growling to make us pee in our pants, the next, he would sway us in the air playfully. He whacked us for misbehaving but also caressed our innate talents. He was the glue that kept us together and the oil that kept us going.

And he learnt it all from his predecessors: mother, father, brother, uncles, and aunts.

Sometime in 1988, when he was still picking up the ropes of his profession, uncle was desperate for a two-wheeler. His new job demanded easy mobility, but he didn’t have enough money to buy a vehicle. Public lighting and road transport in the Kerala of those days were a far cry from today. Crippled by retinal pigmentation, a rare and irreversible genetic visual ailment, his professional survival depended on the bike.

One morning, he casually broached the topic with his grand-uncle, the ex-sailor and a permanent burly presence at the corner pillar of Pullara’s verandah. There was only a mild acknowledgement. But at the end of that day, the sailor handed him a bunch of notes. While we were never poor, hard cash of that kind was rare. “Oh, we sold the corner mango tree,” the sailor said. While this may rankle today’s environmental sensibilities, that was different world. The youngster’s job was at stake and a decision had to be taken.

Such timely interventions have often changed and saved lives at Pullara. And once taken, these were backed by everyone, no matter what the end result. Some of the decisions flopped, but we were all in it together.

My family, like a good section of Kerala society, is matrilineal. The women are strong stakeholders. They are often the decision-makers. My aunt single-handedly manages the finances of almost all of us and dictates the pecuniary. Another aunt was solely responsible for my purchase of an apartment, doggedly pushing a reluctant me.

While I am still at sea with many of these skills, others in the younger generation are already pros at finance, event, and man management; most of us are fair team players, but there also are those exceptional leaders.

“We are like this only”

The mongoose in my backyard, descendant of another long family chain, is lonely nowadays. The mother hen and her chicks have disappeared; and long before that, Lakshmi and her calf. Modernity precludes old farm-economy practices.

The house itself has changed a lot. Two years before the Russian Revolution, when Meenakshi Amma was 16, the thatch roof had given way to tiles and woodwork, using the mango, jackfruit, teak, and Indian rosewood trees from the yards. The next time it was renovated was 92 years later in 2007, in preparation for my wedding. More rooms and toilets added, more space created.

Poignantly though, fewer people live there now.

Most of us who once did are now spread across Mumbai, Bangalore, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait. Yet, we don’t have any other home. Pullara’s where we end up every summer, even if briefly. We don’t make up reasons, for there’s always a wedding, an engagement, a childbirth or an anniversary.

Pity that our kids can’t climb trees to steal cashew fruits or dive into the cool green waters of neighbourhood ponds, because around 100 new and modern houses have taken over the area that we used to run amok in. But then, the outdoors were never our real playground. We picked the most valuable life lessons—of love, sharing, responsibility, forgiveness, and leadership—from the nooks and corners, around the pillars, on the stairs, and in the attic of that grand ancestor of ours. And that’s where we shall all return.

And one day I’ll sit there at the doorstep, quiet and legs stretched, my fading eyes keeping vigil on the ghosts of Lakshmi and her calf, as Pullara’s newest generation flutters by around me.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].