The stories of the first men (and the first woman) to fly in India

Human beings in India first began to fly between March 1910 and February 1911. In the space of a few months, aviation saw its early beginnings—this included the world’s first postal flight on Feb. 18, 1911.

Human beings in India first began to fly between March 1910 and February 1911. In the space of a few months, aviation saw its early beginnings—this included the world’s first postal flight on Feb. 18, 1911.

In December of 1910, a huge patch of ground near the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna in Allahabad was cleared to prepare for an industrial and agricultural exhibition. The timing of the exhibition was crucial: It followed a period of good rainfall, and coincided with the Magh Mela celebrations. In the first months of a new year in 1911, organisers expected a big crowd.

Although the exhibition was initiated by the government, several notables, including the maharajas of Benares and Kishangarh, judges, and other local leaders, were involved with its funding, which took place through contributions and subscriptions.

The exhibition showcased new innovations in agriculture and industry, along with entertainment for the crowds in the form of a bioscope and a laughing gallery (which induced laughter via nitrous oxide). But one of the chief promised attractions at the exhibition was the sight of humans flying. There were to be airplanes and daily flights around the exhibition area, all thanks to the initiative of one captain Walter George Windham.

Windham was a man who wore many hats: He was a diplomat who had served as a king’s messenger, in times when, thanks to rudimentary communication, only a trusted aide was entrusted with such missions; a motoring enthusiast with patents to his name; and a pioneer in the field of aviation.

Windham’s ambitions

One of Windham’s early-design motorcars had seen some success. In 1896, he participated in a motor race from London to Brighton, labelled by motoring enthusiasts as the “emancipation run” because the British government had finally relaxed some of the draconian provisions of the restrictive Locomotive Acts. These acts of legislation had regulated the speed of motor vehicles and even insisted that a man with a red flag run ahead of vehicles (especially if the vehicle hauled wagons) to warn pedestrians away.

Windham had set up his own “detachable part company”—an innovation which allowed the part behind the driver’s seat to be removed and replaced, as and when required. But his attempts to fly his own planes failed spectacularly. These early planes, even those made by other makers—the earliest being the Voisin company in France—were made of light wood (usually bamboo) and fabric, with engines of low horsepower, and familiarities like a tail resembling a kite.

Windham encouraged the efforts for flight in several other ways. He set up the Aero Club and, along with the newspaper Daily Mail, he sponsored the first air flight across the English Channel, from Dover to Calais on July 25, 1909. Despite the rivalries portrayed in the 1965 film, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, there was a lot of Anglo-French collaboration in the making of flying machines those days, and in flight experiments in general.

In 1910, Windham was invited by the organisers of the Allahabad exhibition, and he accepted the invitation without a second thought. The Indian subcontinent was Britain’s most strategic colony—to its north, Russia was keen to expand its influence and posed a clear threat. Here, Windham saw a chance to experiment with longer, uninterrupted flights in different, less windy conditions. He also foresaw the possibility of enthusing the defence services about the possibilities of aviation power.

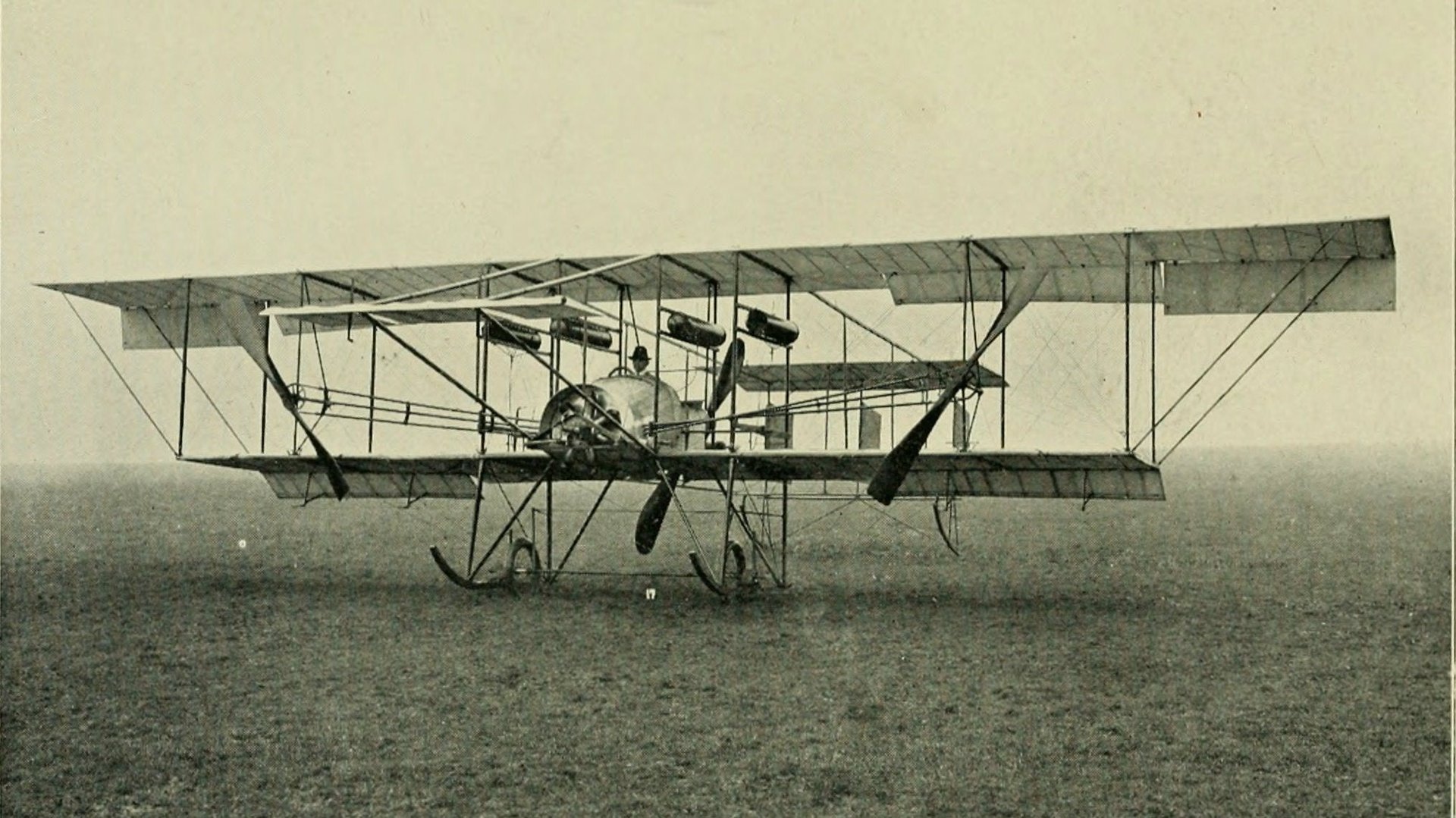

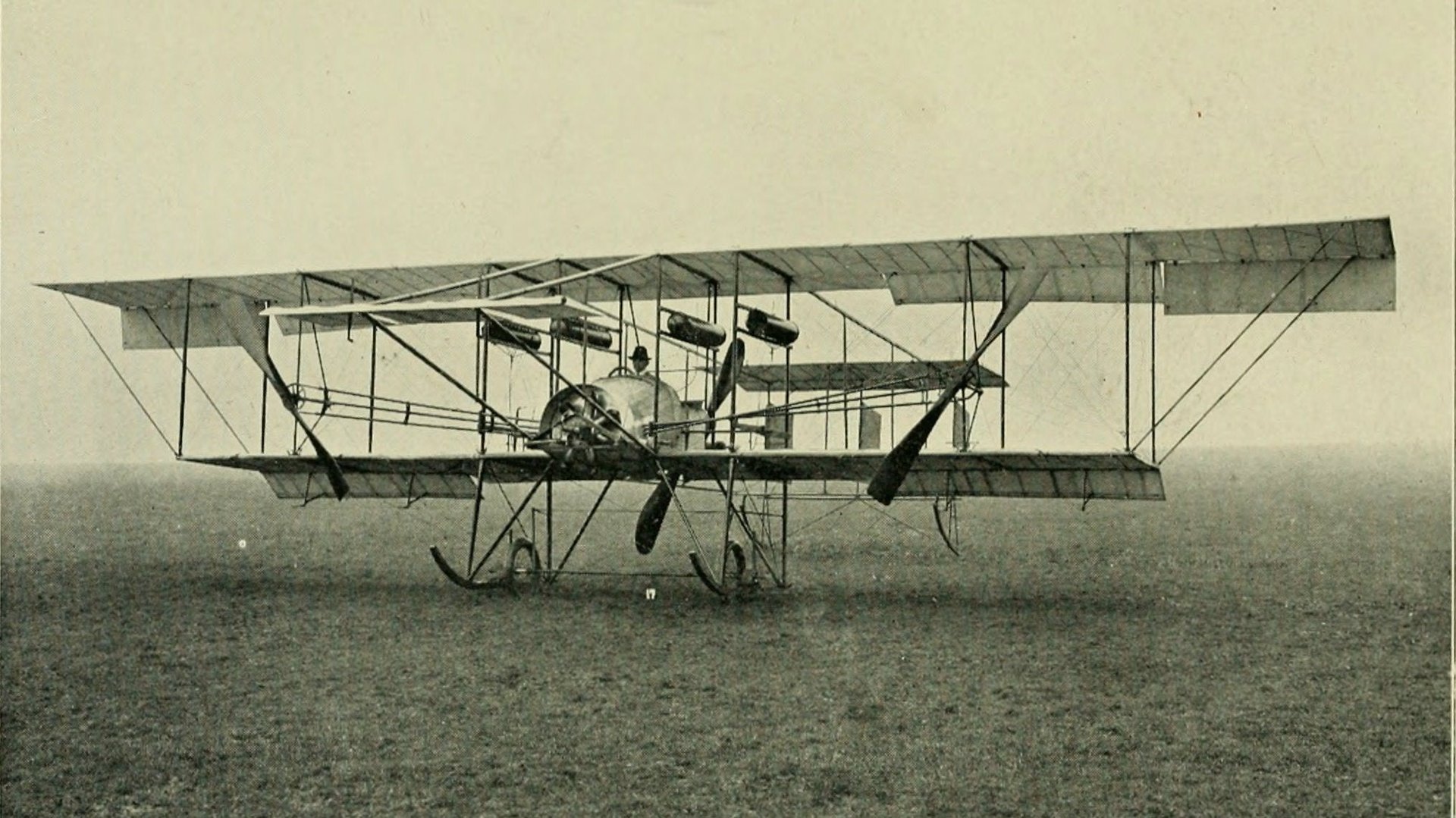

Windham’s planes—six of them—were built by Britain’s Humber company and arrived by a merchant ship, the SS Persia, to Bombay. The planes, dismantled so as to be assembled later with ease, included two biplanes and four monoplanes. Once in Bombay, these were loaded in special wagons and taken by train to Allahabad. Special hangars had already been erected to house these planes, and there were other exhibition structures, all-modelled on the prevailing Indo-Saracenic style (imbibing elements from native architecture, as well as neo-classical and Gothic aspects).

Winged birds over Allahabad

As newspaper reports of the time described it, the planes were assembled over five days and flew sorties over the exhibition grounds on a daily basis, to the delight of the visitors. On Dec. 10, 1910, the English pilot Edward Keith Davies made the first flight in a monoplane, and on one occasion, he took Walter Windham as a passenger. Henri Pequet, the second pilot, flew his biplane the next day on Dec. 11. The maharaja of Benaras is believed to have flown in another one of these flights.

Soon after, the plan for a postal flight came about when the chaplain of the Holy Trinity church in Allahabad, the Reverend WE Holland, approached Windham for help in raising funds for a youth hostel for his Indian students. An aerial postal flight would be ideal, Windham thought, especially to showcase the reliability of aviation during times of war, when towns were besieged on land. No one had an inkling that World War I was only three years away, but war clouds always appeared to loom over the horizon: The Russo-Japanese war had occurred in 1905, and there were constantly skirmishes and wars elsewhere. The Chinese had sent an expedition into Tibet in 1910, and in late 1911, Russia was to enter Tabriz in north Persia.

Windham and Holland, in consortium with other officials, placed advertisements for the public to send in packets and envelopes not exceeding a certain weight (one ounce). A special postmark to mark the flight, created in Aligarh’s postal workshops, was issued. This postmark, apparently designed by Windham, showed a biplane flying over high mountains.

It was 23-year-old Pequet, who had trained with George Voisin (the French aviator and plane-maker) and had earlier flown balloons and dirigibles in places as far afield as Argentina, who made that momentous flight on a Humber-Sommer biplane. He had a watch and altimeter placed on either hand as he took off on Feb. 18, 1911, at 5.30pm. Pequet had to fly across the Yamuna, toward Naini junction five miles away—this was the nearest point on the Allahabad-Bombay line. The land, as has been detailed here, for the craft’s landing had been cleared by convicts at Naini’s Central Jail. The entire trip, from Naini back to Allahabad, took 27 minutes.

The exhibition ended on Feb. 28, when the planes were taken back to Bombay. It was here that Keith Davies made demonstration flights at the Oval especially for the defence forces. Night-time flights were possible only when the grounds were lit up with gas lamps. Back in England, Windham had the same idea for aerial flights to commemorate the coronation of King George V and that was how the flight from Hendon to Windsor in Britain took place later that year in 1911.

An unusual hotelier

Though Pequet made the first postal flight, it was not, as records show, the first flight in India. In March 1910, almost eight months before Windham’s team’s efforts, the Madras-based confectioner-cum-hotelier and flight enthusiast from Messina, Italy, Giacomo D’Angelis, learnt to fly. D’Angelis’ story has been recounted by a descendant who later settled in Chile—He had the idea of devising his own biplane made locally by a company called Simpsons. D’Angelis flew it at the Island Grounds, in Pallavaram in Madras. That first flight turned out to be very successful, and D’Angelis was emboldened enough to ask for volunteer passengers among the gathered audience.

The young boy who volunteered was called Vasan (he later worked in the Kolar goldfields) and knew the poet Subramania Bharati. The latter wrote about this flight in his paper, calling it a creation made by a “British company using Tamil labour.” Perhaps D’Angelis’ effort was a one-off event—In any case, airplane research would soon become hush-hush and expensive, as the military began to wise up to its benefits.

There was also the Belgian aviation pair of Pierre de Caters and the brothers Jean and Jules Tyck, who arrived in India separately toward the end of 1910. They made exhibition flights at Calcutta’s Tollygunge Club after they had been rebuffed by venerable senior bureaucrats in Bombay. While Tyck flew in his Henry Farman aircraft, circling the city for 45 minutes, bringing the crowds below him to a near standstill, Baron de Caters flew for much shorter durations but made 20 quick trips, offering flights to select members among the audience. One of his passengers was the sister of the maharaja of Cooch Behar, known in history books simply as Mrs NC Sen—she may have been the first woman to fly in India, albeit as a passenger.

Windham went on to make a career in aviation, and Pequet and Davies made their mark in exhibition flights. It is ironic that aviation programmes soon after these days of exhilarating first flights concentrated on military ends, more so as World War I broke out. Till the 1930s, Europe concentrated on making airships—those huge, inflatable structures which floated in air—but such initiatives were abandoned after a series of disastrous accidents. Sporadic efforts using aluminium did begin during the World War I years, but gained ground in the 1920s, with the celebrated efforts and rivalry between the American engineer William Bushnell Stout and the Soviet Andrei Tupalov.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].