In Pakistani pulp fiction, the scariest villian is always the Hindu

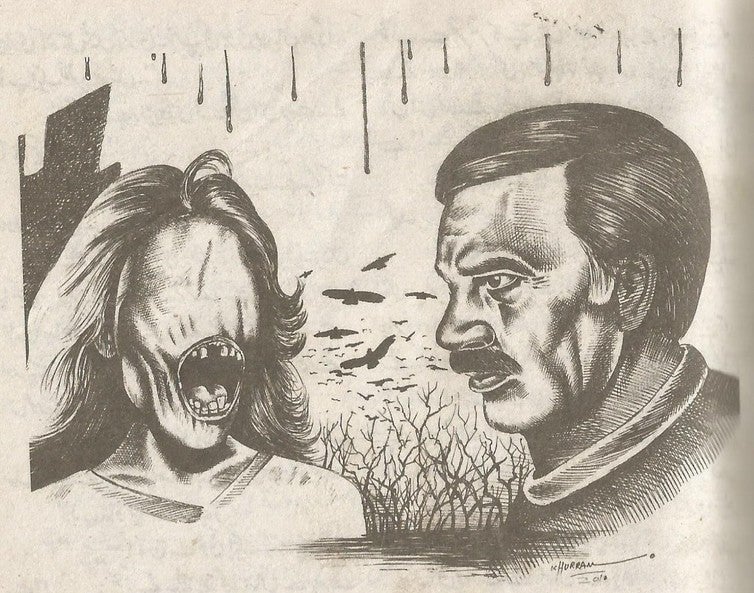

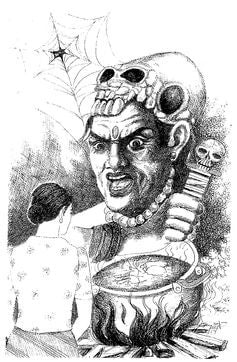

A terrible war is going on in the ghost world. Two opposing sides—the Muslim spirits and the Hindu spirits—face each other in a horrific combat. Suddenly, a gigantic fire-spitting demon with three eyes and a snake dangling from his neck appears on the frontline. The terrible creature reinforces the Hindu side and the Muslim ghosts need to retreat.

A terrible war is going on in the ghost world. Two opposing sides—the Muslim spirits and the Hindu spirits—face each other in a horrific combat. Suddenly, a gigantic fire-spitting demon with three eyes and a snake dangling from his neck appears on the frontline. The terrible creature reinforces the Hindu side and the Muslim ghosts need to retreat.

Thus begins The Wharf of Death (Maut ke Ghat), a ghost story published in the Karachi, Pakistan-based Dar Digest’s January 2015 issue. Such “digests” have a long history in Pakistan’s print media, and these little booklets are widely sold in markets and at train or bus stations, often for about Rs50 (less than a euro).

Each digest is devoted to a particular genre, from detective or science-fiction to love and horror stories. Charmingly idiosyncratic and often ending with deus ex machina figures, their colloquial style entertains a wide Urdu audience, and print runs number from 10,000 to 30,000 copies per month.

One particularly intriguing sub-branch of this genre features tales of horror published in magazines such as Dar Digest (The Fear Compendium), which often combine classical gothic motifs with south Asian mythology. Scenes of dissatisfied jinns (spirits) terrorising their kin, evil snake-demons pretending to be innocent virgins, or haunted house situations (out of which many dear protagonists do not emerge alive) all feature.

Horror and the other

What makes these stories intriguing is their ability to disseminate ideology: The fantastic and the uncanny constitute a smooth canvas for the projection of stereotypes and simplifications.

Free from the fetters of common natural laws, horror stories represent a society’s fears and prejudices. The transgression of the everyday links itself to notions of good and evil and promises creative ways of engaging with what cultural theory calls “the other”. Horror stories are one way of representing evil in a society and the heroes capable of countering these threatening influences.

Hostility (Dushmani), a story from the May 2014 Dar Digest, offers this example:

‘Stop, Dr Shankar!’ A deep manly voice appeared. Dr Shankar, Nirmala and Mohan turned around. An old man with a radiant face and a white beard stood at the laboratory’s entrance door. He was wearing a long white dress and had prayer beads in his hand.

These Urdu tales, composed by freelance authors living all over Pakistan, commonly portray both Hindus and Muslims, frequently revealing a straightforward division between good and evil.

Evil Hindus may plan world domination, sacrifice young virgins for gaining immortality, or simply terrorise others for no obvious reason; their Muslim counterparts, meanwhile, emerge as noble saviours and wise father figures who righteously guard their religious community and the rest of the world from the claws of “Hindu spiritual imperialism.”

Such reoccurring stereotypes reflect a certain view of south Asian history. The Islamic Republic’s central founding myth, the two-nation theory, claims that Muslims and Hindus are two distinct nations that can only thrive when separate.

The movement for Pakistan, however, was not the straightforward development that it is often portrayed as today. While the events that led to the partition of India have many layers of complexity, the simplified notion of an incompatible Hindu and Muslim population continues to be widely promoted in both Pakistan and India. This has often served as a retroactive explanation for the division of the subcontinent.

Ideology’s material existence

We know from Louis Althusser that ideology has a tangible and material existence. Studying ideology, thus, we must begin with institutions, organisations, and media outlets, which are crucial for distributing ideological content.

Ideology in this context does not pertain to right or false consciousness, but rather implies how we perceive the world around us, a process that can be either inconspicuous or blatant.

Discussing cultural identities, sociologist Stuart Hall emphasised how a nation’s story needs to be continuously narrated to its members.

A variety of platforms—such as schoolbooks, TV programmes, and literature—recount a nation’s history and position among other nations and future development. Such forms of media not only describe nations, but also prescribe what it means to be part of them.

Considering Pakistan’s history, the fact that stereotypical depictions of Hindus should resurface in Urdu pulp fiction is unsurprising. In the aforementioned Maut ke Ghat, the spirit world features a variety of constantly warring ghost tribes.

The Hindu ghosts, also described as “immoral Satan-worshipping spirits”, are notorious for their aggression; they attempt to convert every ghost in the netherworld to Hinduism. The story’s foundation is an unavoidable struggle in the spirit world, which renders Hindu-Muslim conflicts as metaphysical truth.

To wit, this excerpt from the tale Kala Mandir (Dar Digest, September 2012):

‘Look son, without becoming Muslim you won’t be able to do anything … Lilavati has nine more days to live. You need to act as soon as possible,’ Babaji explained. Mahindra thought for a bit and then said, ‘Ok. I am ready to become Muslim.’ ‘Mashallah! You have taken the right decision. May God help you,’ Babaji said.

Julia Kristeva meticulously analysed the role of the ambivalent and its relation to the uncanny in her 1982 essay Powers of Horror. Exploring the work of Freud, Lacan, and Mary Douglas, Kristeva develops a distinctive approach to the genre by developing the concept of “the abject.”

Her complex theory is best illustrated by the image of the corpse: It was at one point a living organism, a living character with a certain place in society. But with death this organism becomes a removed object, thwarting its former characteristics. The corpse symbolises a “sudden emergence of uncanniness, which, familiar as it might have been in an opaque and forgotten life, now harries me as radically separate, loathsome”.

In my interpretation of Kristeva, the abject is not understood only as a psychoanalytical category, but also as an historical development: it implies a process in which formerly close elements are rejected to solidify one’s own identity.

As such, the abject position of the evil Hindu surfacing in Pakistan’s pulp fiction can be seen as representative of previous relationships within pre-Partition India that have today been rejected by many parts of society.

Particularly within the context of Pakistan’s nationalist ideologies (which claim Islam as the raison d’étre for the Islamic Republic), “the Hindu” takes on an abject position which is an ambivalent and thus frightening role.

Hindus are, on one hand, a threatening enemy across the border; and on the other, they are the defining and constitutive foundation of the Islamic Republic: a nation allegedly built on the concept of not being Hindu, rather than on simply being Muslim.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at [email protected].