Edward Snowden’s guardian angels in Hong Kong have been abandoned by the world

They had never imagined that a knock at their door one late summer night in 2013 would trigger a dramatic chain of events that would rewrite the course of their lives.

They had never imagined that a knock at their door one late summer night in 2013 would trigger a dramatic chain of events that would rewrite the course of their lives.

Four years on, facing daily threats and the imminent fear of deportation, Sri Lankan national Supun Kellapatha and his partner Nadeeka Nonis say they have no regrets about opening the door. They were glad they welcomed a tall, nervous-looking American man into their tiny apartment.

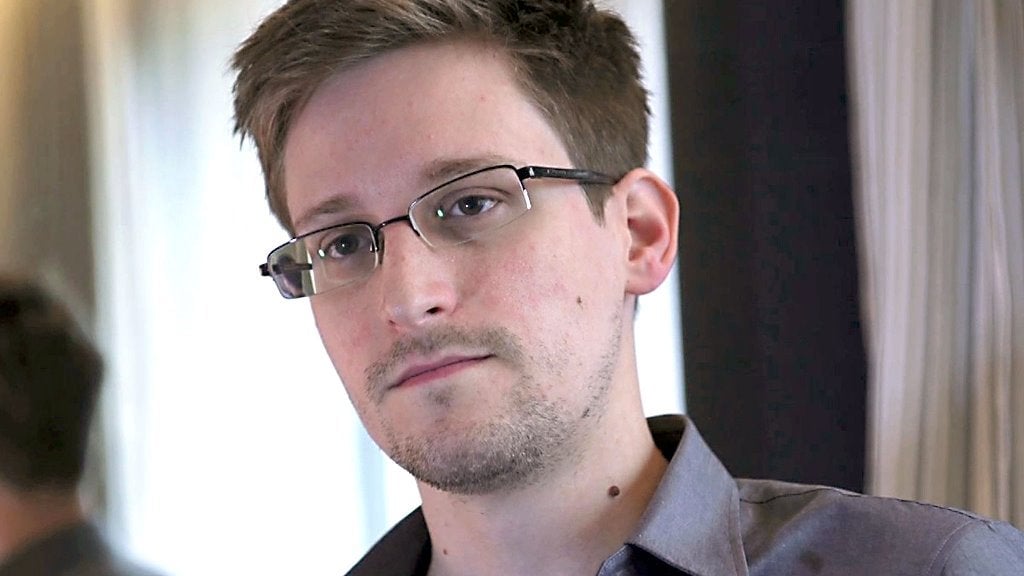

The stranger at the door that night was the whistleblower Edward Snowden—a former US intelligence contractor who leaked thousands of classified government files to journalists from a hotel room in Hong Kong. For two weeks after that leak in June 2013, Snowden was untraceable. As American intelligence agencies launched a global manhunt, the most wanted dissident in the world quietly shunted between the homes of three refugee families in the most impoverished, cramped, filthy, neglected ghettos of Hong Kong before he boarded a plane for Moscow.

Now, the people who sheltered Snowden are themselves looking for protection. As their home countries allegedly try to get them extradited back and remaining in Hong Kong becomes unfeasible, the families are seeking asylum in Canada with the help of Robert Tibbo, the Hong Kong-based human rights lawyer who brought Snowden to Supun’s door that night. Tibbo also represents the refugees.

“We put Ed where no one would look—in a netherworld with people who have an instinct to protect,” said Tibbo. He was confident that this group of people, who had so much to lose if Snowden was caught in their midst, would not betray him or his high-profile client.

They did not.

The refugees—Kellapatha, Nonis and their two children; Ajith Puspakumara, a former soldier also from Sri Lanka; and Vanessa Rodel and her daughter, who are from the Philippines—kept their word and their silence, until the 2016 Oliver Stone movie Snowden revealed where the fugitive hid when he went underground in Hong Kong. It was impossible to keep their names a secret anymore.

Unwitting public figures now, they remain guarded when they speak about Snowden, insisting that they had no idea who he was when they took him in. What they did know was that like them, he too was a refugee—an anxious man outside his home country, looking for shelter.

“Early the next morning, so early that it was still dark, he asked me to go and buy the newspaper,” recalled Kellapatha “I didn’t even look at it till I came back and gave it to him. Then when I saw it, I was shocked.” He looked at the photograph on the front page of The South China Morning Post and asked his houseguest, “Edward, is this you?” To which the stranger replied, “Yes, it’s me.”

“I told him, don’t worry, you are safe,” Kellapatha said.

Kellapatha gave him the only mattress in his two-room apartment that’s no bigger than 125 square feet, while his family slept on the floor. Concerned about what to feed a westerner, Kellapatha bought him spaghetti and burgers from McDonald’s with money provided by Tibbo. He needn’t have worried—what Snowden enjoyed most was Nonis’s homemade chicken curry and daal. “And cake,” Nonis said, as a rare smile breaks out on her face at the memory. “He loves sweets very much.”

Kellapatha and Nonis are both refugees who fled persecution and torture in Sri Lanka. Kellapatha, 32, came to Hong Kong in 2005 to escape political harassment—he says he was ill-treated and tortured by people connected to the political opposition. Nadeeka, who is 33, came in 2007. She is a former seamstress who fled Sri Lanka after years of repeated rape at the hands of a politically powerful man. The couple did not know each other in their homeland. They met in Hong Kong and now have two children together. Their five-year-old daughter and infant son—plus Rodel’s daughter—are stateless because all three children were born in Hong Kong while their parents’ case for asylum is pending.

It could take several years for the Hong Kong government to take a call on their asylum applications. A successful outcome is unlikely, though. Out of the nearly 9,000 refugee claims made since 2009, Hong Kong has approved just 52. That’s an acceptance rate of less than one per cent.

While Hong Kong is not a signatory to the United Nations’ Refugee Convention, it is still bound by a court of final appeal ruling—it must screen asylum seekers to determine if they risk persecution. If they are at risk, they are referred to the United Nations high commissioner for refugees for resettlement to a third country.

According to Tibbo, the refugees who sheltered Snowden are running out of time. Since their names were made public, life hasn’t been the same for any of them. He says they are being targeted by both Sri Lankan officials and the Hong Kong government because of their role in Snowden’s great escape. Sri Lankan officials, he claims, have even harassed the relatives of the asylum-seeking families at home, demanding to know their whereabouts in Hong Kong.

“It’s a matter of life and death,” said Tibbo. He claims he has evidence that Sri Lankan police officials came to Hong Kong to try and track down the refugees—an allegation Sri Lanka denies. If the refugees are forced to return home, they say they fear they will face a violent future.

Here in Hong Kong, they keep a low profile. “We don’t go anywhere, we don’t talk to anyone,” Kellapatha said. “I tell my daughter, you have no friends, we have no friends.”

Neither their daughter, nor Rodel’s little girl, has gone to school since November because the refugees say the International Social Services, the government agency responsible for the welfare of asylum seekers, has withdrawn financial assistance, leaving the refugees with barely enough money for tuition fees or for basic food, clothes and transport in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

They cannot fend for themselves because Hong Kong does not allow asylum seekers to work, study, volunteer or even beg while they wait for the government to determine their status—a process that could take over a decade.

“We have to take our children everywhere we go,” Nonis said. “It’s like having a pet. They just sit, eat and sleep. What kind of childhood is this?” She looks at her five-year-old who has fallen asleep curled up on an office chair in Tibbo’s office.

All three families currently live in “safe houses” organised by their lawyers. They are desperate to get out.

Tibbo is collaborating with three Canadian lawyers who formed a non-profit organisation called For the Refugees to support these families. On March 10, they announced they have officially petitioned Canada to accept these asylum seekers.

On the same day, the families got a big show of support from their grateful houseguest. Snowden tweeted: “The families that sheltered me have formally filed for asylum in Canada. Let us pray Canada protects them in kind.”

Meanwhile, they are living off funds—approximately $100,000 collected by various crowd-funding efforts online.

None of “Snowden’s angels,” as they have come to be known, say they regret risking their lives to shelter him.

“When he left, he hugged us,” said Nonis. “We wanted him to stay forever.”

“I don’t have regrets for helping him,” Kellapatha said. “He told me whatever he did, he did it for the right thing.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].