The slow death of one of India’s biggest startup hubs has begun

It was 4pm on a Monday. At Aromas Café in Powai, five of the 15-odd tables were occupied, and the words wafting from them bore a distinct flavour. On-site. Mobile campaign. Gamification. Have you seen our new app build? You’re still using an iPhone?

It was 4pm on a Monday. At Aromas Café in Powai, five of the 15-odd tables were occupied, and the words wafting from them bore a distinct flavour. On-site. Mobile campaign. Gamification. Have you seen our new app build? You’re still using an iPhone?

Aromas is, from the looks of it, an ordinary café with comfortable couches, but insiders know better. Its central location and free Wi-Fi made it a hotspot—this is where a breed of Powai Valley entrepreneurs hosted investor meetings, made hiring decisions over coffee, and exchanged ideas.

In a few months, though, Aromas feels like a changed place to its regulars.

It was 4pm on a Monday. Words like on-site and mobile campaign wafted from just one table in the centre. Elsewhere in the café, groups of college-goers, young couples, and a mother-daughter duo grabbing an evening snack had very different conversations. Exams. Family matters. Travel.

“A few months ago, every third or fourth table at Aromas, or at Starbucks across the road from it, was from a startup,” said entrepreneurial consultant Uday Wankawala, who works extensively with startups in the area. Now, “that buzz has gone missing.”

This isn’t the story of Aromas, of course. The café, at the centre of startup culture in Powai Valley—the cutesy name given to the northeastern suburb where many of Mumbai’s tech innovations stem from—is a manifestation of the ecosystem as a whole.

Over the past two years, thousands of Powai employees have lost their jobs. At least a dozen startups have shut shop. Investor funding has reduced dramatically—a 44% decline in 2016 from the previous year, according to data from financial research platform NewsCorp VCCEdge.

The success story of TinyOwl, a food-tech company and one of Powai Valley’s poster children, was cut short last year—it stopped services in 11 cities in May, all except Mumbai, and merged into Roadrunnr later. Hundreds of people were laid off. Housing.com’s tale was more infamous—it sacked hundreds in multiple rounds over two years, and merged with realty research firm PropTiger in January. Laundry startup Doormint shut its doors in September 2016. Taskbob closed at the start of this year. Edu-tech firm Purple Squirrel, founded by IIT alumni, folded in May 2016.

“You still see business ideas being discussed at Aromas, but not in the same way, and not as often,” said Jhonny Jha, founder of Powai-based home-services app Didi, who frequents the café. “There’s a serious air now, and discussion tones are more realistic.”

Along with the shifting startup culture, Powai, too, is changing.

Valley of discontent

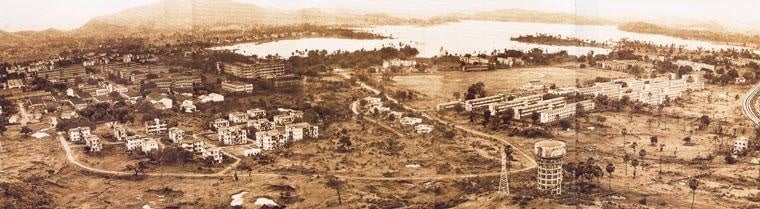

Mumbai’s answer to Silicon Valley had a very different look a little over a century ago.

What is now Powai lake used to be a central village with some huts and a working well. The area today known as Powai Estate, named after a variation of Padma, for a Padmavati temple on its banks, was leased to a Parsi merchant, Framaji Kavasji. In 1890, the British authorities created the Powai lake to increase the water supply to the city of Bombay. When freedom fighter Chandrabhan Sharma bought Powai Estate from its then owner in 1943, the deal was for five villages.

Modernisation arrived in the neighbourhood more than a decade later. In the late 1950s, prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited Sharma personally and convinced him to give a portion of the land to the government, to set up an Indian Institute of Technology, for free. At the same time, Danish engineer Søren Kristian Toubro won a large contract in Bombay, and Sharma leased out large tracts of land to him to set up what would become Larsen & Toubro. The area began to modernise also thanks to Sharma’s construction business, GHP Corp. According to GHP, Prashant Apartments was the first modern building to come up in Powai after IIT, in 1975, followed by the 13-storey Bhawani Tower.

In 1986, the Hiranandani Group signed a tripartite agreement with the Maharashtra state and Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority to develop 230 acres of land and construct affordable housing. After an initial phase of making low-cost homes, working on basic infrastructure, and planting 100,000 trees, by the end of the 1990s, the group changed its strategy to upmarket housing and neo-classical architecture. Their township project, Hiranandani Gardens, began to include upscale entertainment destinations, and even a shopping mall. When the dispute went to the supreme court, it said: “We feel so sorry that private land was purchased by the government and given to you for development. That place was meant for below middle-class people. But you built palaces for those who can afford Bentleys and Ferraris.”

Food historian, writer, and restaurant consultant Rushina Munshaw-Ghildiyal moved into Powai 14 years ago and lived through this boom.

“Powai has pretty much transformed before my eyes,” she said. “As a child, Powai to me was the boondocks. When I moved in, there were just a few metro luxuries, a couple of neighbourhood restaurants we would frequent, Crossword bookstore. When Hiranandani Gardens developed into an upscale destination, so did areas around it, including the Saki Naka side. Now we have on-trend gourmet restaurants, international clothing, and salon brands, buzzing nightlife, a strong café culture. Powai became an entertainment hub, spurred on by real-estate development and demand from the young population that was moving in.”

The lakeside suburb became the startup hub of the city about a decade ago—partly because it houses IIT-Bombay, which churns out (and incubates) a number of tech-based startups. Young entrepreneurs, taking cues from Silicon Valley in California, invested hefty money into the culture of their companies—expansive, colourful offices, crowded teams, and high-paid talent, stemming largely from the IIT-B campus.

“Until not very long ago, if you were an entrepreneur, Powai was the cool place to be,” said Aseem Khare, founder of Powai-based home-services company Taskbob, which recently shut operations.

That boom is progressively losing its sheen in Powai, as in Maharashtra. Across the state, the number of startups that received Series A funding declined by 58% in 2016, with only 28 deals being made, as against the 66 in 2015. Also, the total value of these deals reduced from $292 million in 2015 to $137 million in 2016. Series B funding took a major hit, too, clocking a 46% decline in deal value. Startups raised a total of $72.85 million from 16 deals in 2016, compared to the $135 million raised from 24 deals in 2015.

“I was suddenly asked to leave, and it was very upsetting,” said Mohammed Bilal, who lost his job at Housing.com, eight months in, at the end of 2015. “It was the start of my career, and totally unexpected. I had been enjoying the work, and had great respect for my colleagues and the company. With no notice, I was asked to leave immediately.”

A similar fate befell a 23-year-old employee of TinyOwl who was let go suddenly. “It was my first job, and I wasn’t expecting it,” he said, on the condition of anonymity. “Our team was small, and we knew that people were being cut around the company, but there were many teams that could use slimming down before ours. It was a fun, young office. I realise now, though, that TinyOwl had no revenue model. They invested in a massive office and hired highly paid people only because they were pumped with investor money. A fall was inevitable.”

He is now a freelance photographer. Bilal has gone back to studying.

“I’m pursuing a degree in pharmacy, and want a traditional, stable job now,” said Bilal. “My friends who still work at Powai startups are worried. You never know when a company might shut down.”

The aftermath typically affects those in the 22-26 year age group, says Wankawala. “There are alarm signals for many employees, most of whom are young and might want to start something of their own. There’s a marked shift in enthusiasm and motivation from eight months ago. The layoffs and shutdowns have turned life upside down for a lot of people, but it shouldn’t drive the right ones away.”

Cleansing process

In a way, this is a healthy phase, say industry experts. This consolidation means that investors are taking cautious calls, determining those with solid revenue models.

“This is a necessary cleansing process, and the sense is that there will be an impact on startups banking solely on investment,” said Poyni Bhatt, chief operating officer at IIT-B’s incubation centre, Society for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (SINE). “Real startups will now do well—those trying to solve real market problems, with solid revenue streams.”

The two surviving large-scale startups in Powai, both spawned by IIT-B alumni, are CredR and Toppr, both of which haven’t shown strong growth in recent months. A lot is riding on their success—it could re-instill faith in the market, bring about positive sentiment.

“The honeymoon phase has ended,” said Rupesh Kumar Shah, former CEO of InOpen, a SINE-incubated ed-tech startup that Shah eventually exited. “Irrational seed-funding has stopped, and investors have realised that inorganic growth is foolish. The mood is not entirely pessimistic, but nobody’s investing in pure optimism anymore.”

People don’t know whether there will be bonuses or appraisals, said Khare of Taskbob. “Many VCs and founders are shifting base to Bengaluru. Employees are therefore looking to move out, too.”

Because of mass layoffs, existing companies have many more resources to choose from. Responses on job offers are much higher, and people are willing to work at lower salaries. Sand-hued Powai Valley, with American-style street names, skyscrapers, and a culture largely built to cater to young, aspiring entrepreneurs, is struggling with an identity crisis as an after-effect. Will it get its mojo back? It depends on how the last companies standing fare over the vital next few months.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].

Feature image by Adhishb at English Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.