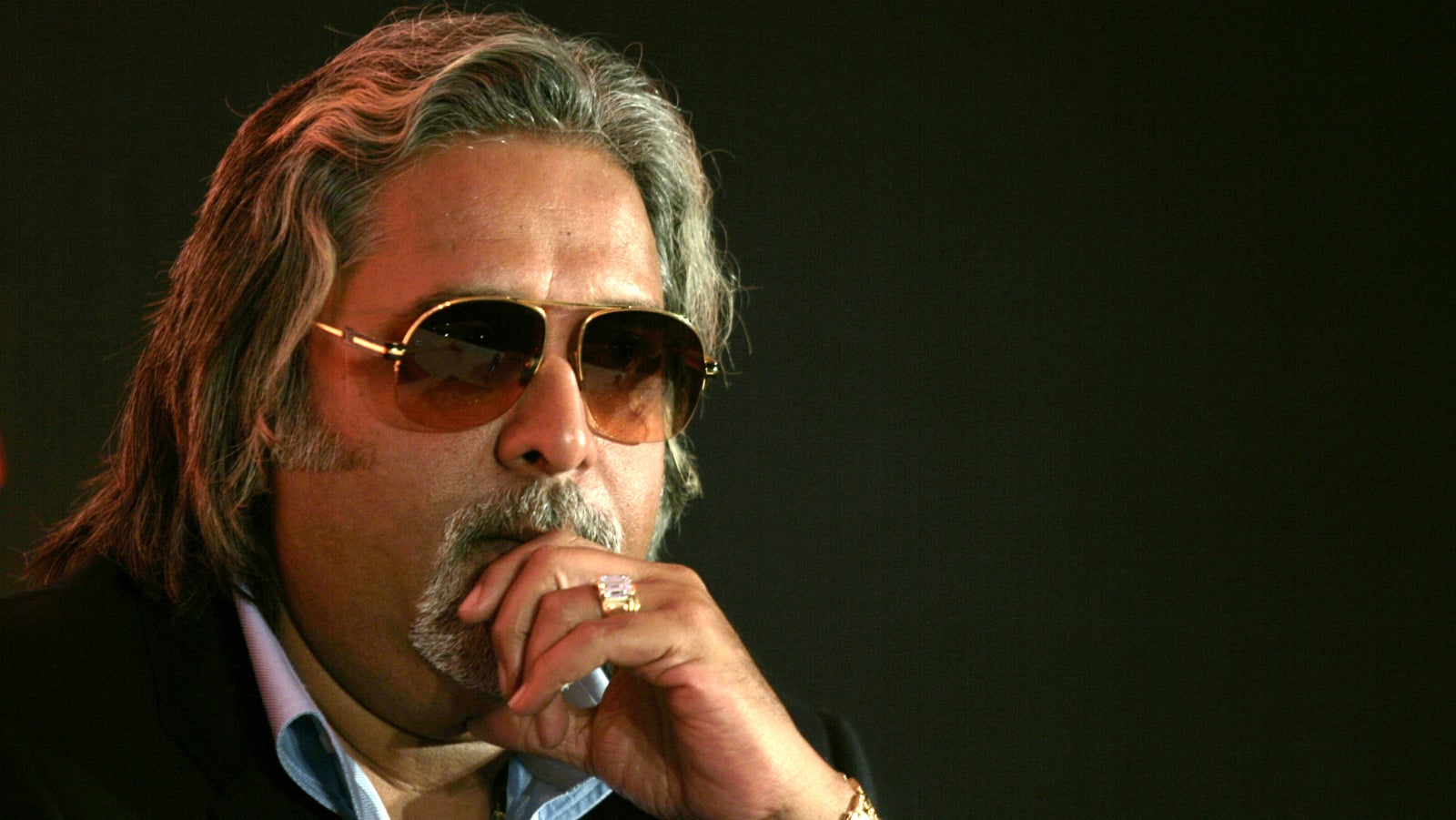

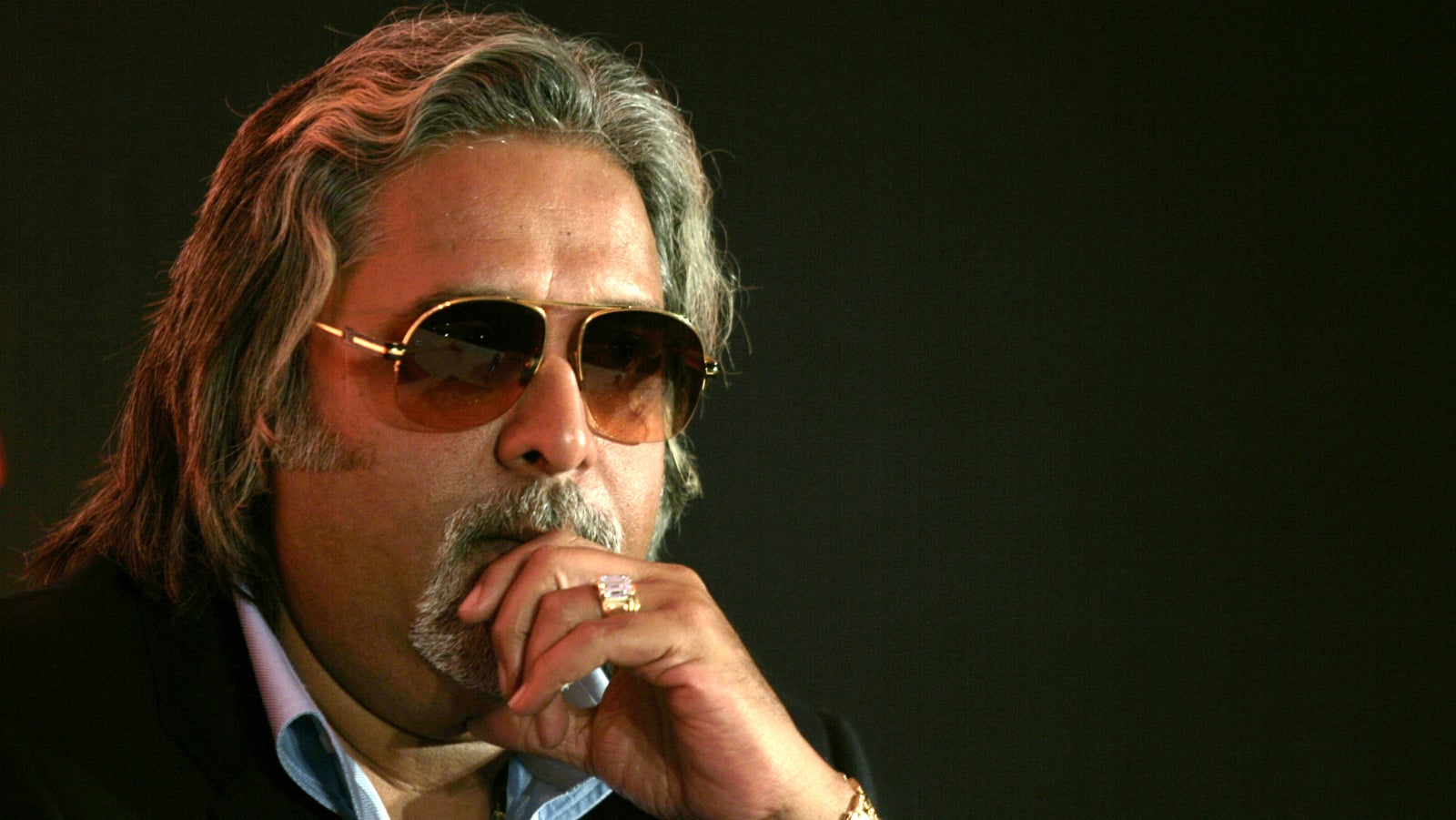

It’s going to be a long time before Vijay Mallya is brought back to India—if at all

On April 18, the Narendra Modi government was ecstatic over the arrest of fugitive businessman Vijay Mallya.

On April 18, the Narendra Modi government was ecstatic over the arrest of fugitive businessman Vijay Mallya.

“It is a big success of the Indian government and the finance ministry,” Jitendra Singh, a minister in-charge of the prime minister’s office said. A BJP spokesperson, too, attributed Mallya’s arrest to the Modi government’s “relentless efforts and commitment to act.”

However, within three hours of his arrest, Mallya was released on a bond of £650,000. The flamboyant businessman quickly turned to Twitter and said “(e)xtradition hearing in Court started today as expected.” Mallya is a permanent resident of the UK, although his Indian passport was cancelled by the Indian government in April 2016.

So how will the legal process pan out—and will India be able to bring him back quickly?

Not easy at all

“Although the UK and India have a long-standing extradition treaty, there has reportedly been only one successful extradition from the UK to India previously,” said Jenny Barker, Of counsel at London’s Peters and Peters law firm.

The India-UK extradition treaty came into effect on Dec. 30, 1993. The existing policy allows for numerous appeals and the rules consider grounds such as breach of human rights in the country requesting extradition, political victimisation, and the passage of time.

“This is likely to take months or years to complete, and there may well be several further hearings,” said Barker. “Mr Mallya would have to establish, using evidence, that one of a limited number of ‘bars’ to extradition applies. For example, he could argue that his return to India would violate his human rights, or that the charges are politically motivated.”

Earlier, too, British courts have refused extradition requests on grounds of human rights violation. “In Badre v Italy [2014] EWHC 614 (Admin) the court gave a judgment recognising overcrowding in Italian prisons,” Karishma Vohra, a lawyer at London based 4-5 Gray’s Inn Square, wrote in a report.

In the past, India has made several such requests. These include high-profile cases involving the likes of musician Nadeem, wanted in the case of Bollywood producer Gulshan Kumar’s murder; Tiger Hanif, wanted in a 1993 Gujarat blast case; and Ravi Shankaran, accused of passing on sensitive defence information. The only successful instance of an extradition to India was that of Samirbhai Vinubhai Patel, accused in a 2002 Gujarat riots case.

Extradition hearings typically take place in two stages: a preliminary hearing, followed by an extradition hearing, Vohra wrote in her report. Even if a verdict is pronounced by the extradition magistrate, the appellant can delay the process through a string of appeals in the UK.

“An extradition judge’s decision can be appealed to the high court within 14 days. Either party can apply against the high court decision to the supreme court, but only if the high court has certified that the case involves a point of law of general public importance,” Vohra explained.

After that, it goes back to the UK government. “Once an extradition decision has been made by the court, it will go back to the secretary of state to make the final extradition order (unless one of a very limited number of statutory prohibitions apply),” said Barker. “Both the court’s decision and the secretary of state’s decision can be appealed, potentially all the way up to the supreme court, and the appeals process can take many more months to complete.”

If that wasn’t enough, the UK was thrown into political uncertainty on April 18, with prime minister Theresa May calling for snap general elections. Irrespective of how the tables turn, the Modi government may have to contend with a new government.

So much to do, and so little time.