Everybody has an opinion on what yoga is for and no one’s got it right

They say Jesus could walk on water, and turn water into wine. Many have postulated that he was a yogi, with siddha powers. That he must have learned it in a Hindu or Buddhist monastery in India during his missing years. This yoga-of-power is very different from the popular, and sanitised, yoga-for-fitness of the global village, or the yoga-for-devotion of the religious and the spiritual.

They say Jesus could walk on water, and turn water into wine. Many have postulated that he was a yogi, with siddha powers. That he must have learned it in a Hindu or Buddhist monastery in India during his missing years. This yoga-of-power is very different from the popular, and sanitised, yoga-for-fitness of the global village, or the yoga-for-devotion of the religious and the spiritual.

Often dismissed as tantra, yoga-for-power remains under the radar despite its widespread popularity owing to its association with the paranormal, the sexual, and the hierarchical. No one wants to suffer the sneer of the know-it-all rationalist. But the question remains: what is real yoga?

Considering its vast history and geographical spread, the greater reliance on oral rather than textual transmission, the complex use of words in various languages, and the fondness for symbols and metaphor, the answer to that question will always remain elusive, notwithstanding classification games of academicians and politicians.

Real yoga?

Today, any understanding of yoga is often obscured by a grand media war to dominate the discourse on yoga. On one side are academicians from American universities who are determined to prove how yoga has nothing to do with Hinduism, or religion, or casteism, in order to serve the interests of the huge yoga market in the US.

On the other side are Indian politicians, who with the support of spiritual gurus and religious leaders, and troll armies, are hard at work to reclaim yoga for Hindus—doing everything from establishing International Yoga Day to erecting gigantic busts of Adiyogi in the middle of once pristine forests, to establishing vast business empires using the yoga brand, to holding public office and declaring that ethical governance can only be done by yogis who shun pleasure, and not bhogis who crave pleasure.

Academicians accuse Indian politicians of sentimentality, which ignores their rigorous scientific method, while Indian politicians question academic methodologies, rooted in atheism, as more driven by activist agendas than by the genuine spirit of enquiry.

Yoga versus tantra

Globally, yoga has become popular as a secular non-denominational tool to relax and de-stress. For religious and spiritual Hindus, yoga cannot be separated from devotion—the quest to unite the individual consciousness (jiva-atma) with the cosmic consciousness, or God (param-atma).

But there is another side of yoga that few talk about, one that is based on power, magic power, one that transforms a man into superman, or vira, as we learn in Sanskrit texts, granting him the power to change his shape and size, his ability to attract people and conjure things, break the limitations imposed by gravity and time. These are the siddhis—the yogi who obtains it becomes a siddha.

This yoga is steeped in mysticism (accessing alternate realities) and the occult (using that alternate reality to impact mundane reality). It is the world of alchemy, aura, spirits, energy, magic, and sorcery. It is firmly in the closet as no one wants to be ridiculed for such irrational and unnatural beliefs. Those who are brave enough to talk about it tend to rationalise it using what scientists disdainfully refer to as pseudo-science.

People want to believe that there is more to life than the mundane, something real—beyond money, status, family, relationships, body, and death, something that defies measurement, and logic, hence control. Many yoga masters offer that alternative reality, without losing sight of the material and the mundane. In fact, they seem to know how to use that alternative reality to control the material and the mundane: solving seeming unsolvable problems, and using this ability to attract voters, customers or disciples, who adore them no matter what they say or do. Who could resist such hypnotic power?

This yoga-for-power has long been classified and dismissed as tantra because of its association with the body, especially gender and sexuality, even caste. This neat division of Hinduism into the Vedanta school of yogis who transcend sex, and the tantra school of bhogis who indulge in sex, emerged in the 19th century, following the documentation of Hindu customs and practices by European Orientalists and Hindu reformers, both steeped in Victorian values.

Hindu supremacists insist that the importance given to the tantrik school—with its association with meat, narcotics, and sex—is misplaced, and part of the Western or Christian agenda to defame Hinduism, fuelled by hippie hysteria. They prefer the puritanical view of Hinduism, mirroring Christian puritanism that links celibacy to power and social service.

However, on the ground, such divisions are artificial and academic, and more a function of propaganda than practice.

Right from Vedic times, we find a tension between yoga-for-power and yoga-for-wisdom, even before the rise of yoga-for-devotion a thousand years ago, and the rise of yoga-for-fitness a hundred years ago. On one side we have ritualists (brahmanas) who seek material indulgences, with their knowledge of astrology (jyotisha-shastra) and geomancy (vastu-shastra) and medicine (ayurveda), and on the other, the ascetics (shramanas) who seek spiritual liberation (mukti). But the division is not so clear.

Later in Puranic times, Shiva is revered as a yogi, which simultaneously means one who withdraws from nature and also with immense power to manipulate nature at will. As an ascetic, he sits on icy mountains away from villages, smeared in ash. But his divinity is established by his ability to give the gods a seed that needs multiple wombs for its transformation in his son, the warlord Kartikeya. Thus, he appears like a shramana, but seems to have the powers that were sought by the brahmanas.

And Vishnu, who engages with the world, as son and husband, and fights wars, is able to multiply himself and be present at different places at the same time, while at the same time advising people to be detached. Both Shiva and Vishnu are considered yogeshwaras, lords of yoga. Yet, they play key roles in tantra too.

So the question remains: what is the goal of yoga? Is it samadhi (liberation from the material, and union with the spiritual), or for siddha (powers from the spiritual to control the material)? Is the whole point to nourish humanity, or to dominate humanity? Does a guru, blessed with knowledge and power, help his students find their path, or does he spellbind them into doing his bidding, like a cult leader? Is the archetypal sage one who gives sermons and creates a school of thought, or one who gives curses and boons, and orders the gods to do his bidding?

Gender and yoga

At the heart of yoga is the awareness of the body, hence gender. The male form is considered superior to the female form as men can retain semen (male seed) while women lose their menstrual blood (female seed) during their periods. Power is obtained by retaining semen, hence the valorisation of the practice of celibacy.

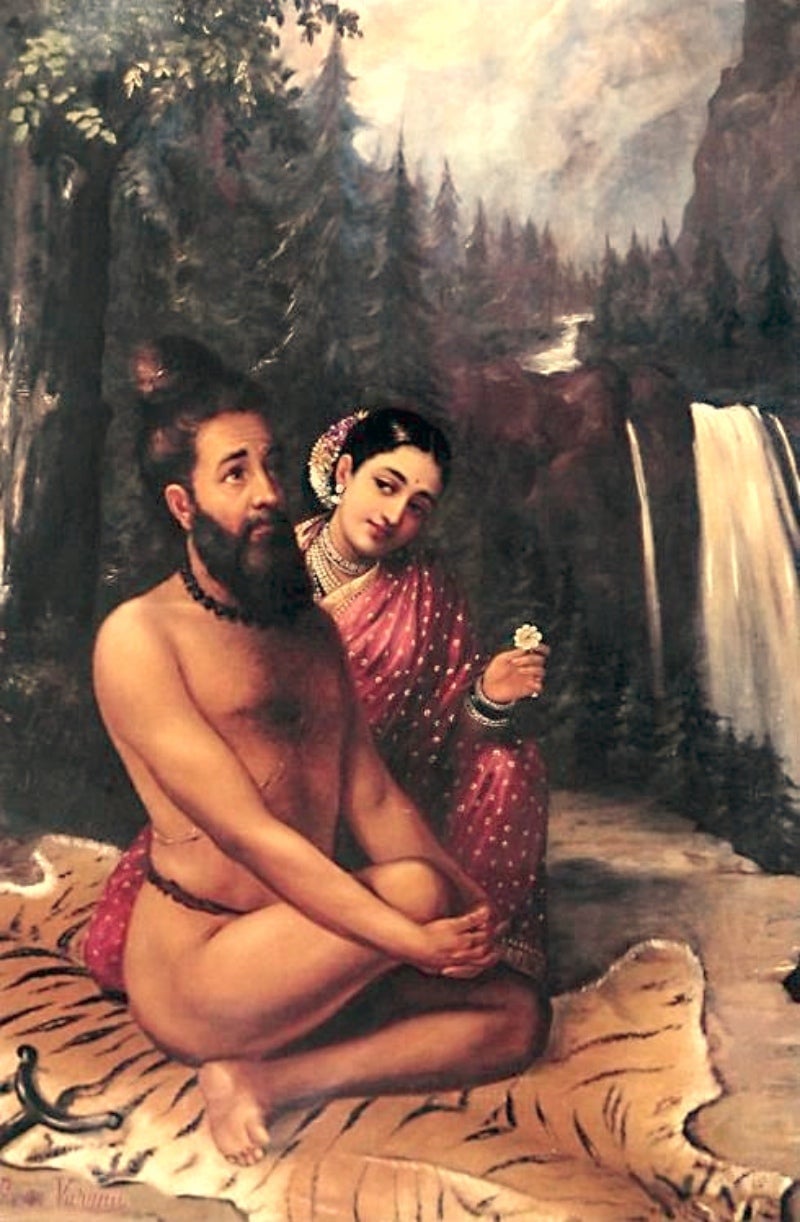

Retained semen can be charged using various spiritual practices like meditation and chanting. It rises up the spine like a serpent (kundalini), opening up nodes (chakra), and eventually flowering in the brain. Whether this is material or metaphorical remains a matter of opinion. In art, an erect phallus on a sage whose eyes are shut represents this. Western mythologists lazily qualify the erect phallus of a yogi as a fertility symbol, not realising it is the exact opposite. When the lotus blooms in the brain, or the mind, the seeker gets wisdom to break from the material world and immerse with the divine (samadhi) and/or the power to manipulate it like a god (siddhi).

For the male ascetic seeking samadhi or siddhi, the greatest threat is the woman. She is the temptation, the seductress, the Menaka to the Vishwamitra. So in Nath yogi folklore, one hears stories of female fiends known as yoginis who get their power by seducing men and yogis. Their queen lives in an enchanted banana grove (kadali vana), which may be a metaphor for women’s quarters, as Sanskrit literature often equates the thighs of a woman with the banana trunk. Any man who enters this grove becomes a woman, except a true yogi. Hanuman, for example, lives in this grove—guarding these women who are priestesses of the Mother Goddess—unaffected by their charms.

Matsyendranath, however, succumbs to the charm of the yoginis, and their queen entraps him until Matsyendranath’s student, Gorakhnath, comes to his rescue, entering the land of women disguised a woman (his yoga powers enable him to resist yogini magic) and he reminds Matsyendranath of his true calling: the spiritual, not the material; the world, not the household; the masculine, not the feminine.

In Hindu temples, a god is always associated with a goddess, indicating the balance of impersonal nature, visualised as female, and personal consciousness, visualised as male. Their marriage is celebrated in grand ceremonies. However, there are always temples of single gods and single goddesses. These are deemed to be “hot” deities, whose power is potent and fierce. Hanuman falls in this category.

Traditionally, men did not visit the shrines of hot goddesses and women did not visit the shrines of hot gods. Over time, only men visited both shrines, a result of patriarchy. Now, as a result of feminism, everyone wants access to all temples, thus the idea of hot is losing its meaning, as is the idea of god’s marriage. Gods are being stripped of their gender and sexuality in a feminist world.

Caste and yoga

The concept of purity and removal of impurities is core to mystical and occult traditions around the world. In yoga too, there is great value placed on the idea of purification. Nowadays, people link spirituality with vegetarian food because it is non-violent, which means there is less contamination with blood. Likewise, spirituality is linked with celibacy, because it means less contamination with body fluids. Spirituality demands cleanliness and hygiene. All these seem very good ideas. We admire the guru and his disciples who carry their own water and will not touch dishes used in kitchens contaminated with flesh, or not purified by holy thoughts and chants. Spiritual cleanliness is rationalised as the scientific concept of hygiene. What is left unsaid is that this concept of spiritual cleanliness that enables yogic union with divine and yogic power has a strong connection with caste hierarchy.

We cannot have an honest conversation on caste anymore as we have been conditioned by academicians, activists, and politicians to see casteism as evil and nothing but evil. We are condemned for appreciating how caste contributed to the diversity of thought, customs and beliefs, even in yoga.

Different yogas emerged differently in different castes. However, everyone—from academicians in the West to Hindutva politicians of India—insists there is one real and pure yoga, and more often than not, it is in Sanskrit, written by Brahmins, even though in lore Patanjali, who composed the yoga-sutra, is identified as the serpent around Shiva’s neck. Could that refer to a member of the snake catcher community? Do names like Matsyendrath and Gorakhnath refer to fishermen and cowherd communities respectively?

There is a tendency to read oral traditions of the elephant groom, the cowherd, the farmer, the weaver, as mere reflections of the upper caste idea, and not original content. Or the tendency is to go to the other extreme, Brahmin yoga writings are an appropriation of the lower caste yoga. All rational analysis can thus be traced to a political stand.

Yoga teachers came from all communities. There were priests, philosophers, dancers, singers, musicians, cobblers, butchers, craftsmen, carpenters, weavers. The social obsession with purity meant that those who transmitted the Vedas, or those who performed rituals within temple complexes, isolated themselves from other communities. They did not dine together.

How were ideas exchanged? Many yogis, like Buddhist and Jain monks, rejected social hierarchies and went to the forest and wandered the land. They embraced the impure, and they returned with wisdom about the mind, the body and the world. These men who transcended caste became gurus. Their followers, who heard their words, followed the caste rules, yet incorporated yogic ideas in their daily practice. Thus a dialogue was maintained between those who lived in the world without caste, and those who lived in a world with caste.

Today where everything is about social activisms, we want to turn yoga into a tool that also enables justice and equality. But was that ever its goal? It remained the instrument for the individual, enabling him to cope with the demands of caste-based society, enabling him to connect with the caste-indifferent divine, and acquire powers that enabled him to dominate and succeed in society. The low caste man could get the high caste man to touch his feet by simply leaving the social order and becoming a yogi, preferably attached to a great yogic school.

Of course, it was not so easy. Caste permeated into yogic practices. In rituals such as shava-sadhana, involving dead bodies, preference was given to the skull of men or women of specific caste. And in rituals like maithuna-sadhana, involving sex, men were encouraged to seek as their guides women of particular castes, each of whom had access to particular occult wisdom.

Religion and yoga

Then comes the big question: is yoga Hindu, or Buddhist, or Jain, or Indian, or secular, with no geographical roots? Like land, and wealth, ideas are becoming territory in a world increasingly dominated by capitalism. And so the communist mindset fights back. Each one frames yoga in a way that suits its own politics, and funding source. And as a good academician knows, classification is power.

When Buddhism is taught around the world, focus is given to its rational and mindful side. Yet, in art, despite all talk of Buddha as an idea and state of mind (Buddha-chitta), Buddha is represented as a male form. We are told that is historically accurate though images of Buddha came into being almost 300 years after he passed away, and are based on Greek ideal notions of beauty.

The Buddha shunned women and his order permitted female monks with much reluctance. The women had more rules in the monastery than men. This had nothing to do with patriarchy. Or did it? Even the homosexual pandakas were listed as men who could not be ordained. Was that homophobia? Or did this have to do with the belief in the limitations of the female biology and the power of the male biology?

The female Buddha was designed in China, almost 1,500 years after the Buddha. Images of Tara became popular in Assam, Bengal and Odisha (Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, of the Puranas), and the exotic East of Nath folklore where yoginis lived in their enchanted banana grove. Coincidence? Nearly 1,200 years ago, in Odisha was born Padmasambhava, who took Tantrik or Vajrayana Buddhism to the Himalayan kingdoms. Popular teachers and academicians insist that is not real or original Buddhism, thus exerting their power to classify, and weed out that which makes them uncomfortable.

We do not want to see how the Buddhist Tara and the Hindu Kali have much in common with each other, or how Buddhist Padmapani and Vajrapani and Hindu Vishnu and Hanuman, have so many overlaps. The exchange of ideas that happened took place not necessarily in sabhas and mandapas of the upper castes, but in the bazaars and the brothels and bathing ghats where all castes came to gossip.

Whose yoga is it?

In the 19th century, academicians created categories like nation-state, religion, caste, and gender to explain various social and psychological phenomena. Over time these functional concepts became rigid entities. As soon as that happened, a new kind of conflict emerged, with these neo-categories serving as levers for various political agendas, arguments and war.

The study of yoga is a victim of these classifications and subsequent hierarchies. Depending on the agenda being served, yoga becomes global or Indian, Hindu or Buddhist or secular, theist and atheist, religious or spiritual, patriarchal or feminist, a technique that enabled men to resist the charms of women, and the burdens of society, or a technique that enabled men to appreciate women and cope with the burdens of society.

Ironically, these academicians, activists and politicians are so busy talking about yoga, and fighting for yoga, that they forget the most popular definition of yoga in the yoga-sutra of Patanjali: chitta vritti nirodha, uncrumpling of the crumpled mind. When this happens, categories collapse, hierarchy disappears, and one is able to appreciate a world that is full of categories and hierarchies. Armed with the knowledge, we can either fight the world to change it, using activism or occult powers, flee from this world that cannot be changed, or freeze and allow the world to change itself on its own terms.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].