ispace’s missing lander shows how hard it is to touch down on the Moon

Japan's ispace made the latest failed attempt to safely put a robot on the lunar surface

Hopes were high, but viewers watching the faces of the flight controllers at ispace headquarters in Tokyo could see the news was bad. The company lost contact with its Hakuto-R moon lander as it sped toward the lunar surface, and now fears that it is lost.

Suggested Reading

ispace was attempting to become the first private organization to land a spacecraft safely on the Moon. Launched onboard a SpaceX rocket in December, the company’s lander had travelled to the Moon and now began a controlled descent toward its surface. The final transmissions from the vehicle reported it was less than 80 meters (262 feet) above the surface, moving at 30 km/h (19 mph).

Related Content

While engineers worked to regain contact with the vehicle, CEO Takeshi Hakamada said the company had to assume a failure. He congratulated his team for getting as far as they did, noting that lessons from this mission will improve the company’s planned second and third attempts to reach the Moon.

Hours later, the company said that its analysis suggested that the lander, while in the right position, ran out of fuel during the landing attempt and, without being able to slow its descent, crashed into the lunar surface.

This is the third recent failure to make a soft landing on the Moon; the Israeli non-profit SpaceIL and India’s space agency both made failed attempts in 2019. The last successful soft landing was made that same year by China’s Chang’e 4 lander, which was also the first to land on the far side of the Moon.

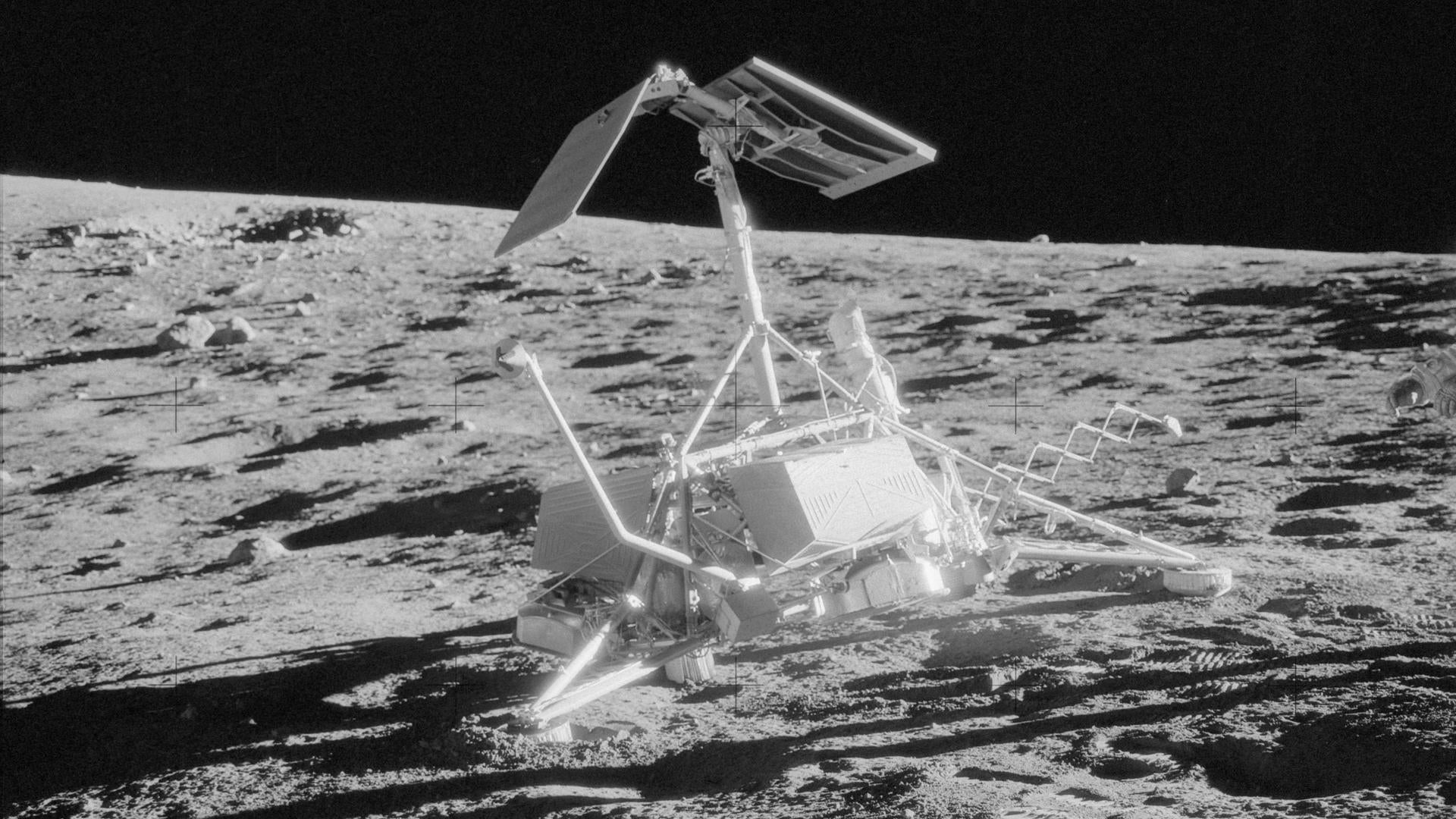

Besides China, the Soviet Union and the US are the only countries to safely deliver scientific instruments to the Moon. Both nations suffered dozens of failures before making successful landings in 1966.

What makes a lunar landing so tricky?

There’s just not enough air, and too much dust.

When a spacecraft lands, whether on the Moon, Mars or returning to Earth, it needs to slow down so that the gravity of its target can pull it in. With the Earth and, to a lesser extent, Mars, the biggest initial challenge is the atmosphere of the planet: When a vehicle leaves the vacuum of space and rams into a big wall of gas, the collision generates a lot of heat energy. That’s why spacecraft returning to Earth or landing on Mars carry heat shielding to protect themselves. But after they get through the atmosphere, they can use parachutes to slow themselves down efficiently.

The Moon, however, barely has an atmosphere, so parachutes aren’t an option. That’s convenient when it comes to heat shielding, because the vehicle doesn’t need to carry the extra weight. But it does need to be able to use its engines to slow down and stick the landing, which also means that limited stores of fuel create little margin for error. Given ispace’s initial conclusions, that might have been what went wrong here.

Even with enough fuel, the second concern comes in—the lunar surface is covered in a material called regolith, a mixture of dust, rock, and even glass fragments. During the crewed Apollo missions to the Moon, there was even some worry that a large spacecraft might sink down into the surface. But the real problem facing astronauts is that the dust tends to get everywhere with much gravity helping hold it down. That applies to landings, too: When a spacecraft is landing autonomously, its rocket thrusters could throw up dust that interferes with its sensors and leads to the wrong maneuver, or turns a flat landing area into a crater.

The truth is out there

We won’t know exactly what happened to Hakuto-R until iSpace’s engineers have carefully analyzed the data sent back by the spacecraft. NASA’s Lunar Reconaissance Orbiter will also pass over the landing site, and imagery that it captures could help explain what happened, as it did for the last two failed attempts.

In the most recent failures, SpaceIL’s Beresheet lander suffered an engine malfunction before crashing into the surface, while India’s Chandrayaan-2 suffered an unspecified software glitch that apparently led the vehicle to impact the planet at high speed.

This story has been updated with additional information from iSpace.