Joe Biden made the oil trade of the year

How the White House defanged Russia and OPEC with the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Gas prices were a major story in 2022: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine roiled energy markets and some predicted the US dollar might be subsumed by a new, commodity-backed trade currency.

Suggested Reading

Instead, it appears the US government made the oil trade of the year: Releasing 180 million barrels of crude from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve between March and the end of this year in an effort to blunt the effect of rising prices, the US government appears to have made about $4 billion, as prices have fallen dramatically over the course of the year.

Related Content

Selling when crude oil prices were high, the US captured billions in value. By one widely-used measure, the price of crude oil in Texas peaked at about $124 a barrel in March, and the average price during the SPR sales period was about $96; today that oil costs just $73 per barrel.

These are paper profits, to be sure: The US is still aiming to refill the reserve, and prices may rise as it does so. On Dec. 16, the Department of Energy put out a request to purchase 3 million new barrels of crude, after releasing about 200 million barrels in 2022. There are currently about 382 million barrels still in reserve.

Why did Biden release oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

The use of the SPR helped the US weather geopolitical storms by moderating increases in energy prices driven by sanctions against Russia after it invaded Ukraine in February. At the same time, the nations that coordinate as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries plus other aligned countries (OPEC+) have curtailed production in an effort to protect the value of their fossil fuel resources by slowing the fall in prices.

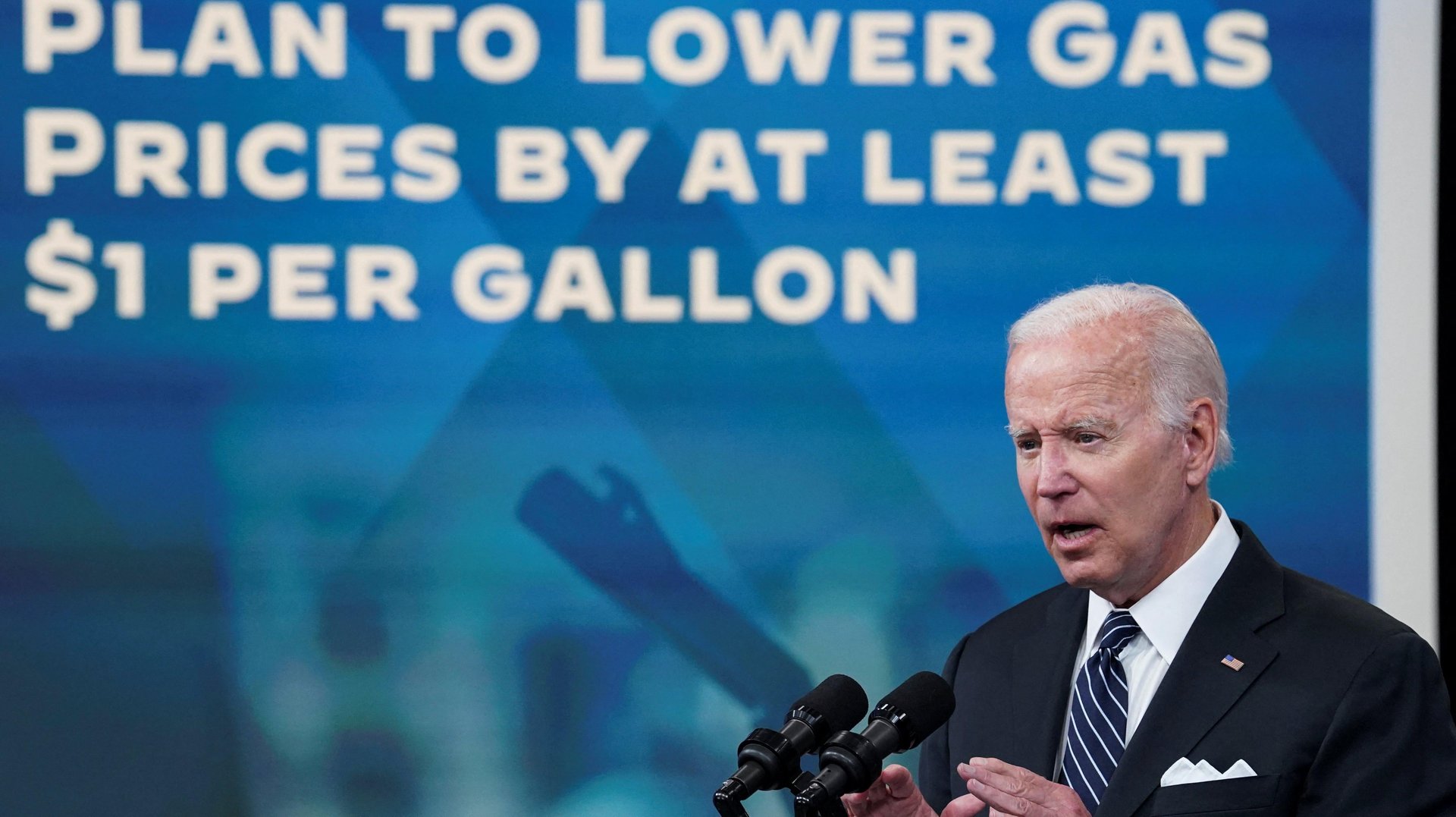

The SPR releases appeared to have a material effect on gas prices: After peaking in June at a national average of $4.80 a gallon, American gasoline prices have fallen back to $3.10. That’s higher than immediately before the pandemic but lower than average prices in the first half of the 2010s, before the widespread adoption of fracking turned the US into an oil-producing powerhouse.

Whether you see OPEC’s October decision as an attempt to influence US domestic politics or not, the SPR has helped insulate both Americans and the rest of the world from high energy costs. While much has been made of the decision’s effects on US markets, the releases meant lower prices globally. Russian president Vladimir Putin was apparently confident he could use his country’s oil production as a weapon against Ukraine’s allies, but the arrival of winter (and the rising cost of heating) have yet to collapse their resolve. That’s in part thanks to the SPR releases and other efforts to increase energy supplies.

The real trick is buying low

Releasing oil when prices are high is a pretty straightforward tactic. Now, some economists and policy analysts want the SPR to use its market influence more broadly. Employ America has argued that the SPR should use futures contracts to put a floor on the price of crude oil, which would realize those profits but, more importantly, help achieve a stable level of production.

Oil companies in the US were reluctant to invest in new drilling this year even as prices shot up; investors preferred them to spend free cash on stock buybacks after years of losses generated by over-production. Now, the DOE has said it will develop rules to buy oil futures at a price level of around $70. That could reassure oil companies that they won’t be undercut by OPEC if they invest in oil that is more costly to extract from the ground.

Some environmentalists haven’t been thrilled about this idea, since all things being equal it will lead to more oil usage and more carbon dioxide emissions. Advocates adopt a kind of climate realpolitik, arguing that abundant supplies of fossil fuels are politically and economically necessary to transitioning to a carbon-free economy: Something has to power the production of renewable infrastructure and keep the economy humming until decarbonization. If energy prices weren’t stabilizing now, the Federal Reserve would likely be hiking interest rates faster, making a recession (and the human misery that entails) more likely.

In the near term, oil watchers are focused on China’s decision to move away from its harsh anti-covid policies. Re-opening could lead to higher prices if demand from Chinese consumers and companies grows, but it’s difficult to predict how rising cases of the virus will affect their behavior.

That’s one reason why those oil futures contracts make sense for the DOE: They can book their profits and give oil producers some guidance going forward. But if a recession does come next year, the price of oil may plunge even further, leaving the government looking a bit foolish. That may be a price worth paying if it helps increase energy supply, but that’s also why some people are skeptical about government agencies speculating like commodity traders.