McDonald's, Big Mac prices, and America's Big Beef problem

McDonald's has joined scores of other firms suing the top meatpackers for raising prices

A version of this article originally appeared in Quartz’s members-only Weekend Brief newsletter. Quartz members get access to exclusive newsletters and more. Sign up here.

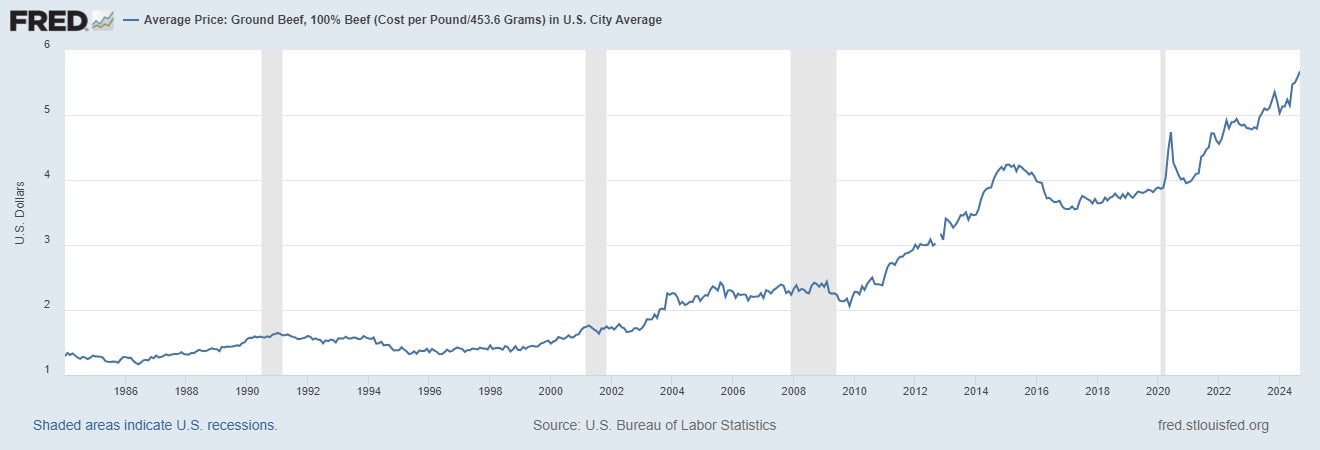

A little more than a decade ago, McDonald’s, America’s largest single buyer of ground beef, noticed that beef prices were surging far ahead of inflation. But it took another five years or so to figure out what was going on. Earlier this month, McDonald’s filed what may be the last of scores of lawsuits filed against the country’s four largest meatpackers — the firms that buy live cattle, slaughter them, and sell the meat (known in the industry as boxed beef) to big customers, from Target and Kroger to McDonald’s.

The lawsuits, which have been consolidated in federal court in Minneapolis for the time being, allege a vast conspiracy among the nation’s four largest meatpackers — Cargill, JBS, Tyson, and National Beef Packing, which together control more than 80% of the U.S. beef market. The complaint alleges that the packers made secret agreements to depress the price they paid ranchers for their cattle, and to increase the price they charged customers for beef, a violation of U.S. antitrust laws.

The suit cites an insider who was employed by JBS-owned Swift Beef Company and who confirmed the firms acted together to fix prices at both ends of the business. The suit also cites public calls by the meatpackers to reduce their capacity to process beef, and alleges that key executives of the four companies held “frequent meetings” at trade conferences and industry events so their contacts would slip under the radar. (Secret meetings to discuss business among people in the same industry can be a violation of antitrust law).

Together, almost 200 lawsuits allege that everyone from cattlemen to meat wholesalers and distributors to end users like McDonald’s have lost billions of dollars because they were either forced to pay too much for beef or were paid too little for their cattle.

The suit also leans on data showing that the number of head of cattle the packers slaughtered each year dropped dramatically starting in 2015.

Beef collusion?

“Only colluding meatpackers would expect to benefit by reducing their prices and purchases of slaughtered cattle because they would know that their conspiracy would shield them from a competitive marketplace,” where rivals would try to steal market share by paying more for cattle and charging less for boxed beef, McDonald’s alleges.

The suit also notes that both the Department of Justice and the Department of Agriculture have launched their own investigations into whether the packers fixed U.S. beef prices. And a 2021 letter from 26 U.S. senators to the Justice Department calling for an inquiry into the price-fixing allegations made clear the industry’s power: “Their collective power over the cattle and beef processing industry allows them to seemingly control prices at their will.”

In fact, as far back as 2018, the General Accounting Office, Congress’ audit arm, took a dive into beef data. It found the market was not behaving rationally and urged a change in USDA rules to give greater transparency on prices to ranchers, buyers, and packers.

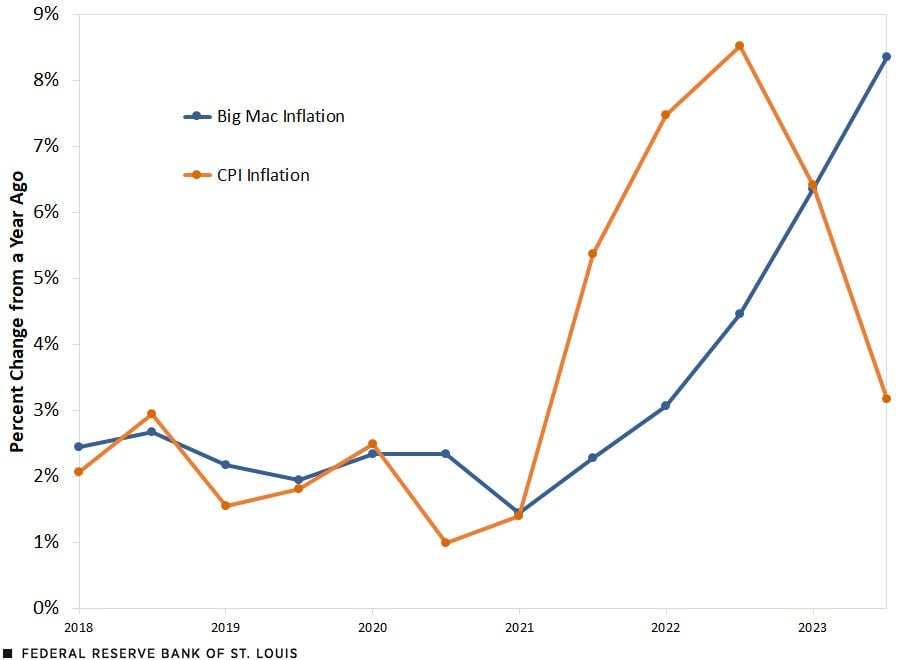

Whether artificially high beef prices are the real reason for the rising price of McDonald’s hamburgers is hard to tell. First off, McDonald’s started using fresh meat for its Quarter Pounders back in 2018, which raised the cost of those burgers because fresh meat is often pricier. (You can’t store it in a deep-freeze for a year, so it’s more sensitive to fluctuating market prices, and it has to be used quickly before it spoils). But the Big Mac Index has more or less been tracking inflation, as the St.Louis Fed reported in April. In fact, Big Mac prices lagged the increase in the Consumer Price Index until late 2022, but have recently started rising faster than inflation.

The four firms and their subsidiaries have denied the allegations in court. None responded to requests for comment from Quartz.

Not everyone agrees that the overall price of beef has gone up all that much. While the price of ground beef, a staple for McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, and others who are suing the packers, has almost tripled since 2010, the price of steak has risen more slowly.

The price of cuts like sirloin has remained relatively constant, noted Pete Zaleski, a professor of economics at Villanova University and an expert on food pricing. He argued that food prices are cyclical and that measuring from peak to peak gives a better sense of beef price inflation. On an annualized basis, he said, the increase in the price of sirloin has exceeded the Consumer Price Index by about 1% every year.

Still, Zaleski added, “It’s probably true for any industry: Negotiating power tends to be with the party that’s more concentrated.” The question, he said, is whether it’s illegal activity that’s controlling prices, or simply the economics of a concentrated industry.

But even small price changes can significantly affect a business like McDonald’s, said Christopher Gaulke, a lecturer in food and beverage management at Cornell University.

“With the volume McDonald’s is doing, they are very very susceptible to even small fluctuations in in basic commodity prices such as beef,” he said in an interview. That’s because profit margins in the restaurant business are typically less than 10%. In fact, Gaulke said, a large part of the rising price of McDonald’s hamburgers is more likely tied to rising labor costs. Minimum wages are climbing across the U.S., and it’s harder — and therefore more expensive — to retain workers.

Paul Savage, the director of commodities forecasting for beef, pork, and poultry products at ArrowStream, a company that serves thousands of restaurants across the U.S., said part of the perception of price gouging may be linked to the cyclical nature of the cattle industry, where it can take several years to replace a herd that’s been culled when feed prices rise or prices for fed cattle — those about to be slaughtered — drop.

The Big Mac big flip

“Right now, the [cattle] farmers are making money, it’s the packers that are barely making any money,” Savage said. In the five years from 2018 to 2023, he said, beef packers were making profits of more than $100 per head of cattle they slaughtered. Now they are barely breaking even, clearing $10 to $20 per head. “But when the packers were making money the farmers were barely breaking even,” Savage said. “In three years it’s going to flip back and the packers will make money again and the farmers will fight to break even.”

The lawsuits currently going through federal court in Minneapolis are expected to wrap up their discovery period next month, then it could take a year or more before the suits are either settled or proceed to trial in jurisdictions across the country.

The beef suits are just one of a number of what one attorney representing a plaintiff against the packers calls “the protein cases,” which target pork and chicken processors, and that together allege a handful of companies have a stranglehold on the U.S. food system. That, said experts who watch the food system, makes the U.S. very susceptible to the kind of supply chain disruptions seen during the pandemic — but also to any disruption in the business models of the handful of companies that increasingly control what we eat and how much we pay for it.

And that, they say, is unlikely to change unless the federal government steps in.

“Without significant government intervention to reduce consolidation in the food system, the potential danger to U.S. consumers is immense,” said Laurie Beyranevand, a professor at Vermont Law School and the director of its Center for Agriculture and Food Systems. “As evidenced by the food inflation we’re experiencing now which is partly attributable to other factors, but also results from unchecked corporate price fixing and other anti-competitive measures.”