How hyper-sensitive satellites could combat climate crises from space

Pixxel's Awais Ahmed will put a constellation of six satellites in space in early 2024

“Like every human has a unique fingerprint, every chemical or material has a unique spectral fingerprint,” Awais Ahmed says. But traditional satellites can’t always read that fingerprint. That’s where an emerging class of highly-sensitive satellites, powered by hyperspectral technology, comes in—and in Ahmed’s vision, it can be used to protect Earth’s environment from space.

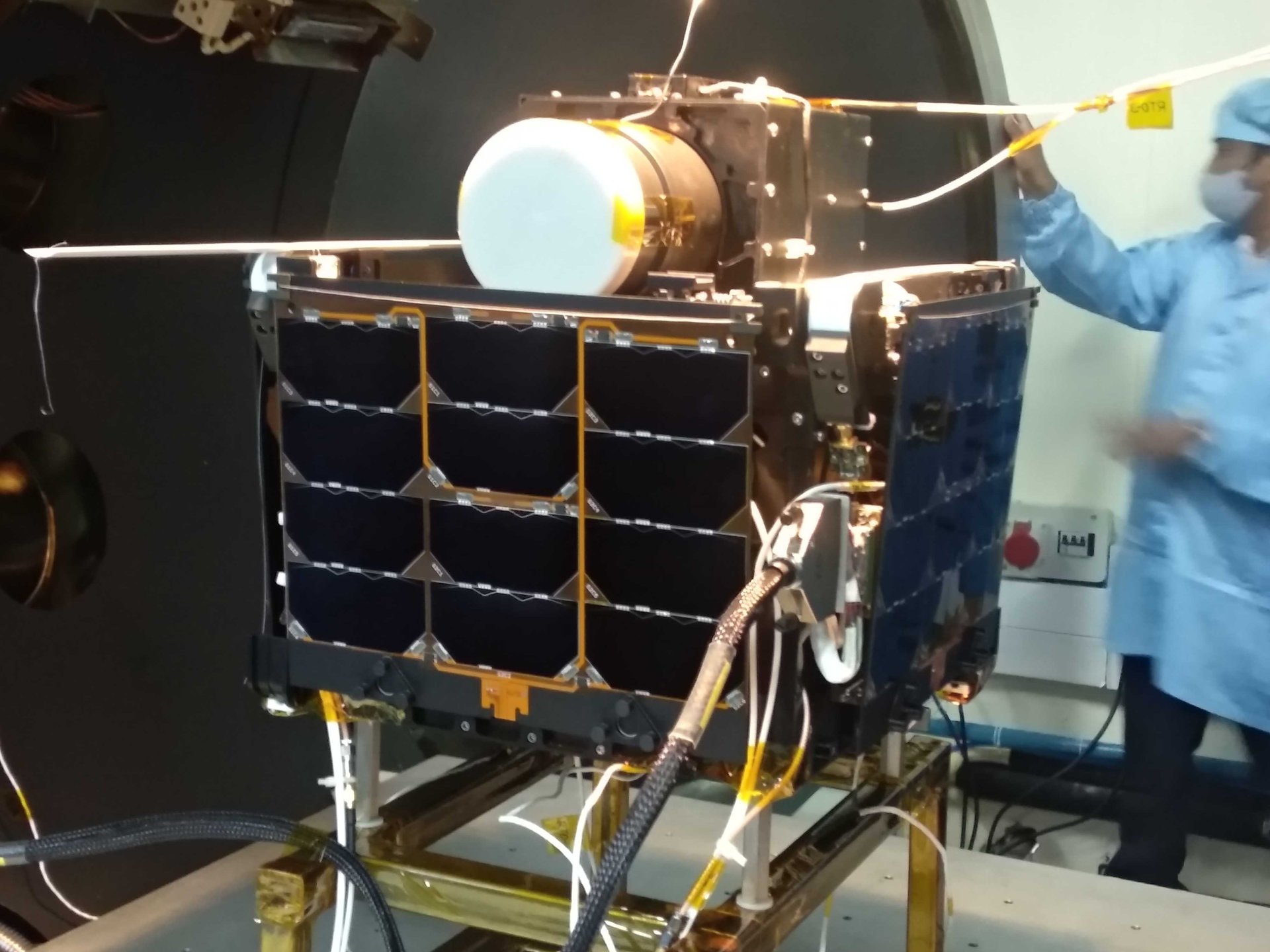

Ahmed is the 25-year-old cofounder and CEO of Pixxel, an Indian startup building satellites outfitted with hyperspectral sensors. When sent into space, hyperspectral satellites can gather data across a wider range of the electromagnetic spectrum than typical space sensors can. After launching its first into orbit last year, Pixxel is now at work building a network—or a constellation—of the high-resolution satellites to watch our planet from outside its atmosphere.

Although NASA launched the first hyperspectral imaging satellite back in 2000, its commercial purpose went untapped—and it was put out of commission in 2017. In Pixxel’s vision, this advanced technology can be used to combat a bevy of climate-related issues, including crop disease, gas leaks, and covert mining.

While a normal satellite image can scope out the basic health status of a given crop, hyperspectral imaging can see soil nutrient content, identify species and subspecies, capture chlorophyll and moisture levels, and catch pest infestations before physical symptoms show up—all sophisticated data that can help prevent the spread of disease in agricultural fields. Meanwhile, heat-trapping greenhouses gases like methane are invisible to multispectral satellites—but not to hyperspectral ones, which can spot leaks and emissions from afar. And while humans map out mining explorations, hyperspectral satellites can determine where lithium, uranium, and other resources are present—along where they’re not, saving areas from excavation.

“Having that snapshot of the earth will help policymakers make better policy, government take faster action, and create a database to see things globally,” Ahmed says.

Ahmed grew up without internet access in a village outside the small city of Chikkamagaluru in Karnataka; raised on children’s encyclopedias and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, he wanted to be an astronaut. But his forays into space technology started in his first year of college, when he began working with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) as part of a student team developing small satellites. The next year, he’d help form a student group answering Elon Musk’s call for teams around the world to build hyperloop pods; they’d advance far enough to meet Musk and tour SpaceX’s factory. (The meeting would later pay off: Pixxel would eventually launch its first hyperspectral imaging satellite with the help of SpaceX’s Falcon-9 rocket.)

Ahmed would become interested in building super-sensitive hyperspectral satellites in his final year of college. With his friend (and now chief technology officer) Kshitij Khandelwal, the duo founded Pixxel in early 2019 as students.

Pixxel raised a pre-seed round of $700,000 from college alumni, with 90% earmarked towards building a satellite. With hardware in hand, Pixxel pulled in $7.3 million in its first seed round. More capital—with a $27 million funding round, then a $36 million round led by Google—followed. Today, the company counts more than 170 employees.

Pixxel’s client roster includes notorious polluters, like oil and gas firm British Petroleum and mining company Rio Tinto, who use its hypersensitive imaging to pinpoint potential toxic leaks and supervise tailing ponds. On the other side of the table, Pixxel works with government agencies like the US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the ministry of agriculture in India, along with as climate watchdogs, to keep an eye on environmental violations.

In a bid to start its constellation, Pixxel has built six commercial-grade hyperspectral satellites, which are currently undergoing testing. The constellation is slated to launch early next year. But Ahmed’s ultimate plan for Pixxel ventures far further than our atmosphere. In another five to seven years, he sees the company working with space agencies “to map out rest of the solar system,” he says, “like we’re mapping out the Earth.”

This story is part of Quartz’s Innovators List 2023, a series that spotlights the people deploying bold technologies and reimagining the way we do business for good across the globe. Find the full list here.