Christian Dior: Luxury is what makes us human

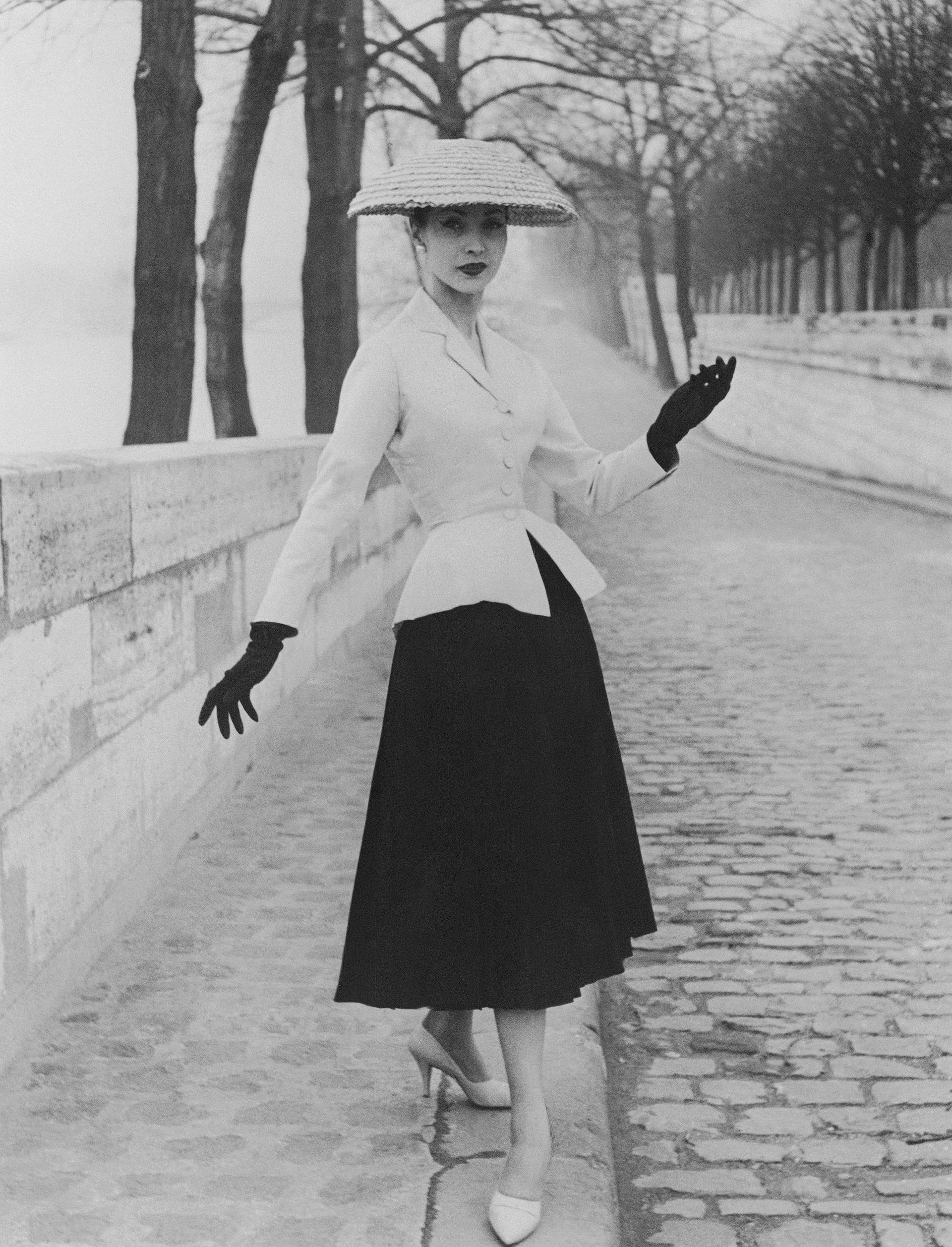

At the heart of Christian Dior’s glittery retrospective at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs is a rather plain outfit: There among the beaded, Versailles-ready gowns is a cream nip-waisted jacket paired with a full, black mid-length skirt. Dior’s so-called “New Look” was a historic a fashion moment when it debuted in 1947. But it was more than that: It was a manifesto for living.

At the heart of Christian Dior’s glittery retrospective at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs is a rather plain outfit: There among the beaded, Versailles-ready gowns is a cream nip-waisted jacket paired with a full, black mid-length skirt. Dior’s so-called “New Look” was a historic a fashion moment when it debuted in 1947. But it was more than that: It was a manifesto for living.

After World War II, Dior drew controversy by opening a luxury brand. Critics called Dior’s lavish use of textiles in the New Look’s voluminous skirt “unpatriotic” in a time of scarcity. Dior’s answer was a powerful defense of luxury as a concept—and as an essential, humanizing element of daily life:

In a time as dark as our own, where luxury consists of guns and airplanes, our sense of luxury must be defended at all costs.…I believe that in it there’s something essential. Everything that goes beyond the simple fact of food, clothing and shelter is luxury; the civilization we defend is luxury.

These days we equate luxury with anything lavish, extravagant and unnecessary. But what Dior, and the French, will remind us is that luxury, in whatever scale, venue or price, is vital.

The French have rescued the word “luxury” from vulgarity several times in history. From the Latin words “luxus,” meaning excess and “luxuria,” meaning “offensive,” luxury was associated with lewd, adulterous behavior in 16th century England. (“She knows the heat of a luxurious bed,” writes Shakespeare to discredit the virtue of Hero in Much Ado about Nothing) The French had a more positive spin with “luxe” (that lead to “deluxe”) meaning wealthy or sublime.

As Dior suggested, luxury can have a more egalitarian definition. While in the US, it’s often about material extravagance, French luxury is about allowing oneself moments of delight, thrills big and small. Yes, it can come in the form of wildly expensive couture gowns, Birkin bags, and Salon champagne, but it can also mean indulging in humble pleasures.

A man from Bordeaux I met on a train told me that to him, luxury is pausing to feel the warmth of the sun on his face every morning. Luxury can be a particularly superb croissant, a good book, or an aimless stroll. Indeed, this aimlessness is essential to the French notion of the flâneur.

A flâneur‘s luxury is time—one that many of the wealthiest and most privileged people cannot afford. A flâneur is able to (if only momentarily) reject all calls, meetings and appointments to seize time for herself—moments spent luxuriating midway between laziness and activity.

Charles Baudelaire says a wanderer’s motive is to “wed the crowd,” and lose oneself in it. “It’s an immense pleasure to take up residence in multiplicity, in whatever is seething, moving, evanescent and infinite: you’re not at home, but you feel at home everywhere,” he explains in the essay The Painter for Modern Life. “The observer is a prince who, wearing a disguise, takes pleasure everywhere.”