LinkedIn glorifies the competitive sport of pathological workaholism

Social media is inherently competitive.

Social media is inherently competitive.

On Instagram, you can’t escape the feeling that your life will never be as well traveled, well dressed, and well-curated, as that blogger with 300K followers (though she may in turn feel inadequate compared to Kim Kardashian). On Twitter, it’s all about how many people respond, favorite, or retweet you. And on Facebook, everyone’s trying to be the cleverest and woke-est (with the cutest baby).

LinkedIn, meanwhile, has become a gruesome arena for competition, in the fight-to-the-death tradition of gladiators. The goal is to prove that you have sacrificed the most or slept the least to achieve success. And that success is measured through Silicon Valley’s startup-style workaholism.

Some of Silicon Valley’s most prominent success stories perpetuate the belief that sleep-deprived hard work is virtuous. In a 2016 interview with Bloomberg, former Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer credited the success of Google to “hard work” in the form of all-nighters at least once a week, sleeping in the nap room instead of walking to the car at 3am, and even being strategic about “how often you go to the bathroom.” Mayer famously did not take maternity leave. “I found ways to make that work,” she said in one interview. (Of course, unlike many women, she had the resources to pay for childcare.)

The celebration of being a workaholic starts long before Silicon Valley, of course. It’s just that Silicon Valley helped globalize this very American way of thinking.

We can blame the Puritans. In fact, we can jump all the way back to the Reformation, when wealthy merchant families began taking on the landed aristocratic families, while reformer theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin were questioning the authority of the ruling Catholic Church, and thus the status quo.

The rise of capitalism also played a role. In the influential tome The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, German sociologist Max Weber argues that Protestant ideals dignified even the most mundane of labor as a form of spiritual calling. Work was no longer just a way to make a living, to keep your family fed and your taxes paid. It became your “calling,” your “purpose in life.”

In high school, many American children read Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack. Franklin’s pamphlet is famous and influential because it is, at its core, about self-improvement. (Along with being an American Founding Father, Franklin was a scientist, author, politician, inventor, and more. Every Silicon Valley bro aspires to be him.)

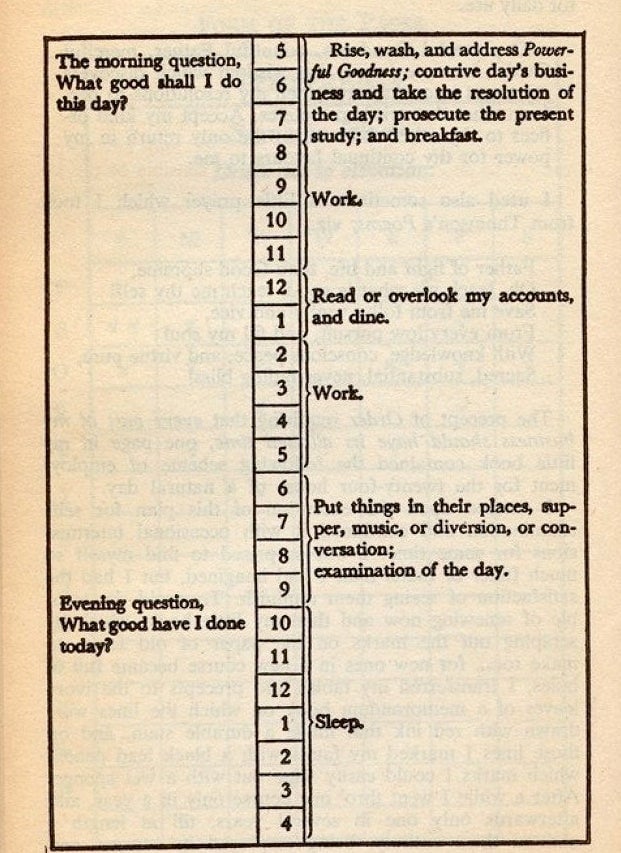

“The morning question,” Franklin writes, is “What good shall I do this day?” Then he records his daily schedule in the text, which involves rising at 5am and going to sleep at 10pm—but not before asking himself his evening question: “What good have I done today?”

Franklin was so obsessed with productivity and self-improvement that he was the founder of a Philadelphia-based self-improvement club called the Junto, or Leather Apron Club.

You can find a modern version of Poor Richard’s Almanack, arguably, on LinkedIn, where people post their daily schedules about rising at 5am to go to CrossFit before a packed but spiritually fulfilling workday. It is, as Jia Tolentino writes in The New Yorker, “the American obsession with self-reliance, which makes it more acceptable to applaud an individual for working himself to death than to argue that an individual working himself to death is evidence of a flawed economic system.”

On LinkedIn, it is about being a “Productivity Ninja”—hacking and optimizing yourself into a so-called value-adding machine, and defining yourself not just by your professional résumé but by how people respond to it. “To be sharper and realize a new potential previously uncharted—I had to make 4am the new 5am,” writes one person, a self-described brand coach, on LinkedIn.

Here’s a new life hack: If you’re the type of person who cares about “adding value,” don’t post your productivity schedule on LinkedIn. Maybe get some sleep instead. You probably need it.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Benjamin Franklin’s bedtime.