Researchers say a new Nike shoe can actually make you a faster runner

Nike has promoted its Zoom Vaporfly 4% as a shoe that could change the future of running. Designed for serious marathoners, the shoe supposedly allows athletes to use 4% less energy during their runs than Nike’s previous top racing shoe, the Zoom Streak 6. That may not sound like an extraordinary amount, but over the course of 26 miles, it could make a huge difference. In theory, a 4% energy savings should allow you to run at high speeds for longer, and Nike believes it could enable an elite runner to finish a marathon in under two hours for the first time ever.

Nike has promoted its Zoom Vaporfly 4% as a shoe that could change the future of running. Designed for serious marathoners, the shoe supposedly allows athletes to use 4% less energy during their runs than Nike’s previous top racing shoe, the Zoom Streak 6. That may not sound like an extraordinary amount, but over the course of 26 miles, it could make a huge difference. In theory, a 4% energy savings should allow you to run at high speeds for longer, and Nike believes it could enable an elite runner to finish a marathon in under two hours for the first time ever.

New research out of the University of Colorado suggests Nike’s claims are more than just marketing. In a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Sports Medicine, researchers report the results of tests comparing prototypes of the Zoom Vaporfly against the Nike Zoom Streak 6 and Adidas’ adizero Adios Boost 2—a version of the shoe Dennis Kimetto used in 2014 to set the record for the fastest marathon in history. Every one of the 18 runners tested used less energy running in the Zoom Vaporfly.

“The prototype shoes lowered the energetic cost of running by 4% on average,” the researchers write. “We predict that with these shoes, top athletes could run substantially faster and achieve the first sub-2-hour marathon.”

It looks like validation for Nike, which started developing the Vaporfly system in 2013. The researchers began their study in April 2016, and Nike released the shoes to the public this July. There’s only one catch: it was a Nike-funded study. Two of the researchers were also Nike employees, and one was a paid Nike consultant.

That doesn’t necessary mean the results are faulty. The researchers disclosed the conflict of interest, and got ethical approval from the University of Colorado Institutional Review Board. But what would an independent expert say of the results?

“Overall I thought the design of the study was good as far as the science that they used,” says Rondel King, an exercise physiologist at New York University’s Langone Medical Center who has studied footwear’s effect on running at NYU’s run lab. King says the researchers’ methods all made sense to him. His main hang up was the small sample size, just 18 runners. “Ideally we would like to see for something like this maybe over 100 [subjects],” he explains.

Wired similarly ran the study by experts at University of Calgary’s Human Performance Lab. “The upshot: It’s a well-designed study with one minor flaw,” Wired concluded. The flaw they identified was that the test runners knew they were running in a new shoe from Nike, which could have created a placebo effect. Previous research has found that a placebo effect on its own can improve performance.

Wired also noted it was a challenge for the researchers to find those 18 test subjects. They looked for runners who could finish a 10k (6.2 miles) in under 31 minutes—not an easy task—and they all had to be size 10, because that was the size of the Zoom Vaporfly prototypes available for testing.

Assuming the Zoom Vaporfly is better, what does it do differently from other shoes? Just about every contemporary running shoe has a midsole made of some foam material. That foam acts like a spring: when you step down on it during your stride, it compresses, storing energy, and then bounces back up as you lift your foot, effectively returning some of that energy to you. The amount of stored energy it returns back to you is called resilience.

Running sneakers also help your foot more effectively utilize the work your leg muscles are doing. As the study explains, “Running shoes can also enhance how the human foot acts like a lever to transmit the force developed by the leg muscles (e.g., the calf) to the ground so that the body is propelled upward and forward.”

Nike’s Zoom Vaporfly is designed to be better at these tasks than other running shoes. It has a curved carbon-fiber plate sandwiched between two layers of soft, springy foam, which makes the sole resilient and helps propel you forward when you run.

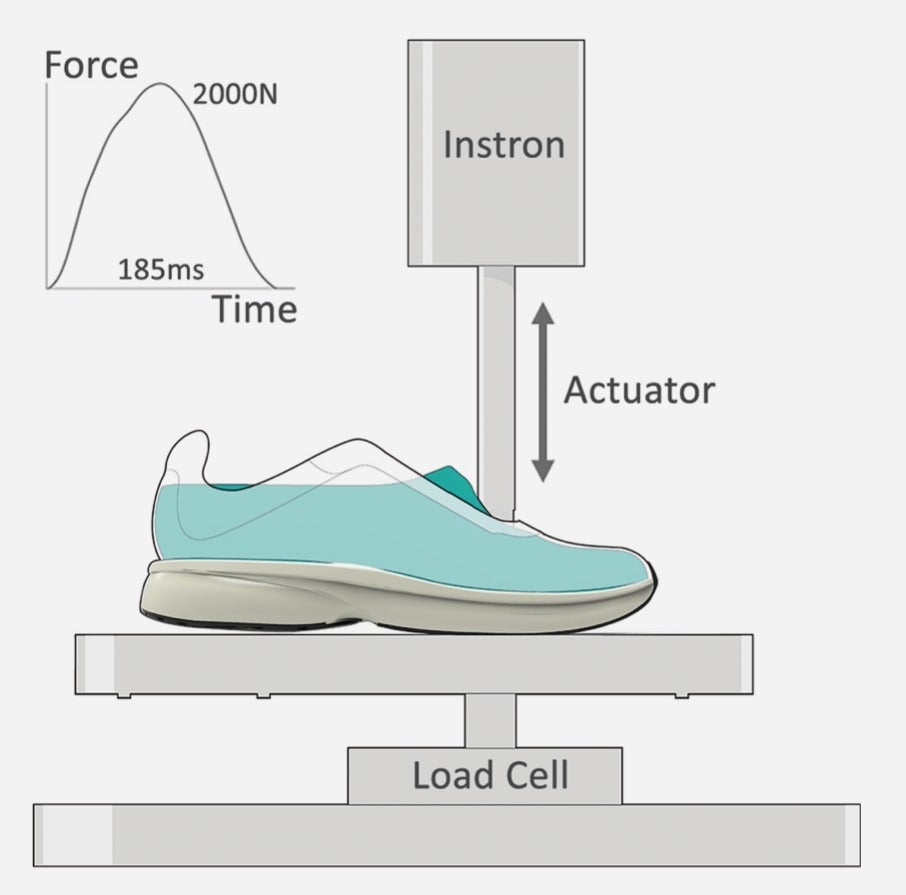

To test the resilience, the researchers used a machine that compresses the midsole much like your foot does when running. The soft midsole of the Zoom Vaporfly stored “substantially more” energy than the other two shoes.

It was also better at returning that stored energy. The Zoom Vaporfly had an 87% energy return, versus 75.9% for the Adidas shoe and 65.5% for the Nike Zoom Streak 6.

“[The study] is essentially saying that the shoe is giving you a biomechanical advantage,” King says. “I can definitely see how this shoe could improve your mechanics and your propulsive forces.”

That word “advantage” raises an ethical quandary. At what point does a pair of shoes start to offer a Nike-sponsored runner an unfair edge over athletes who are sponsored by other brands? There are no clear guidelines on the question at this stage.

Right now, it’s also not clear if it should even be a concern.As Alex Hutchinson pointed out for Outside, though the energy-return numbers are impressive, it’s not 100% apparent how they translate into runners using less energy, which, in this study were calculated using a standard measure: how much oxygen they burned during their runs. We also can’t say for sure how these findings translate outside of lab conditions. Runners have been wearing the Zoom Vaporfly, but their results, while noteworthy, haven’t been abnormally fast. Nobody has completed that sub-two-hour marathon just yet.

It could only be a matter of time, though. In May, Nike had some of the world’s best distance runners complete a marathon in custom Zoom Vaporfly shoes. Eliud Kipchoge, the world’s best marathoner, finished in two hours and twenty-five seconds.