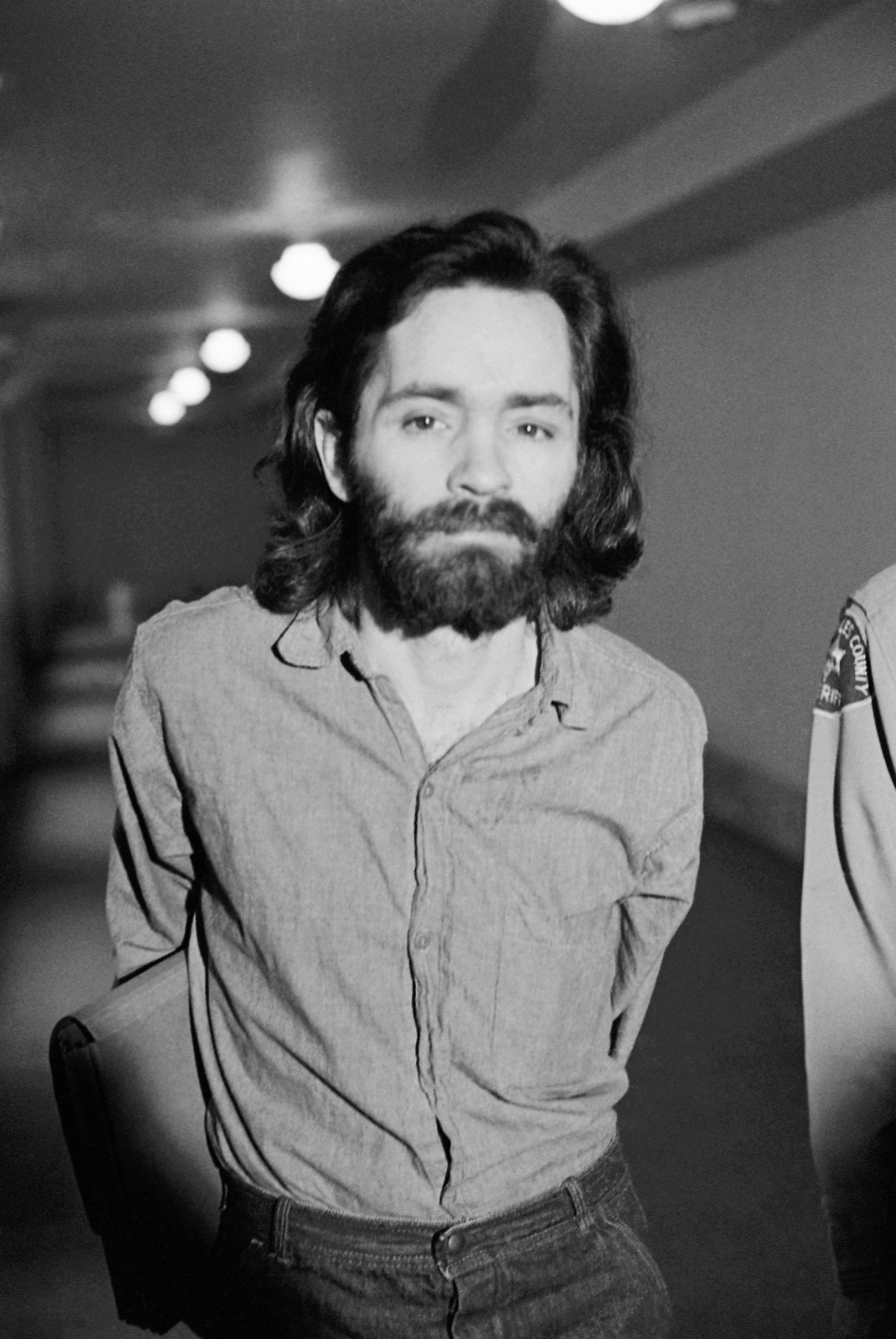

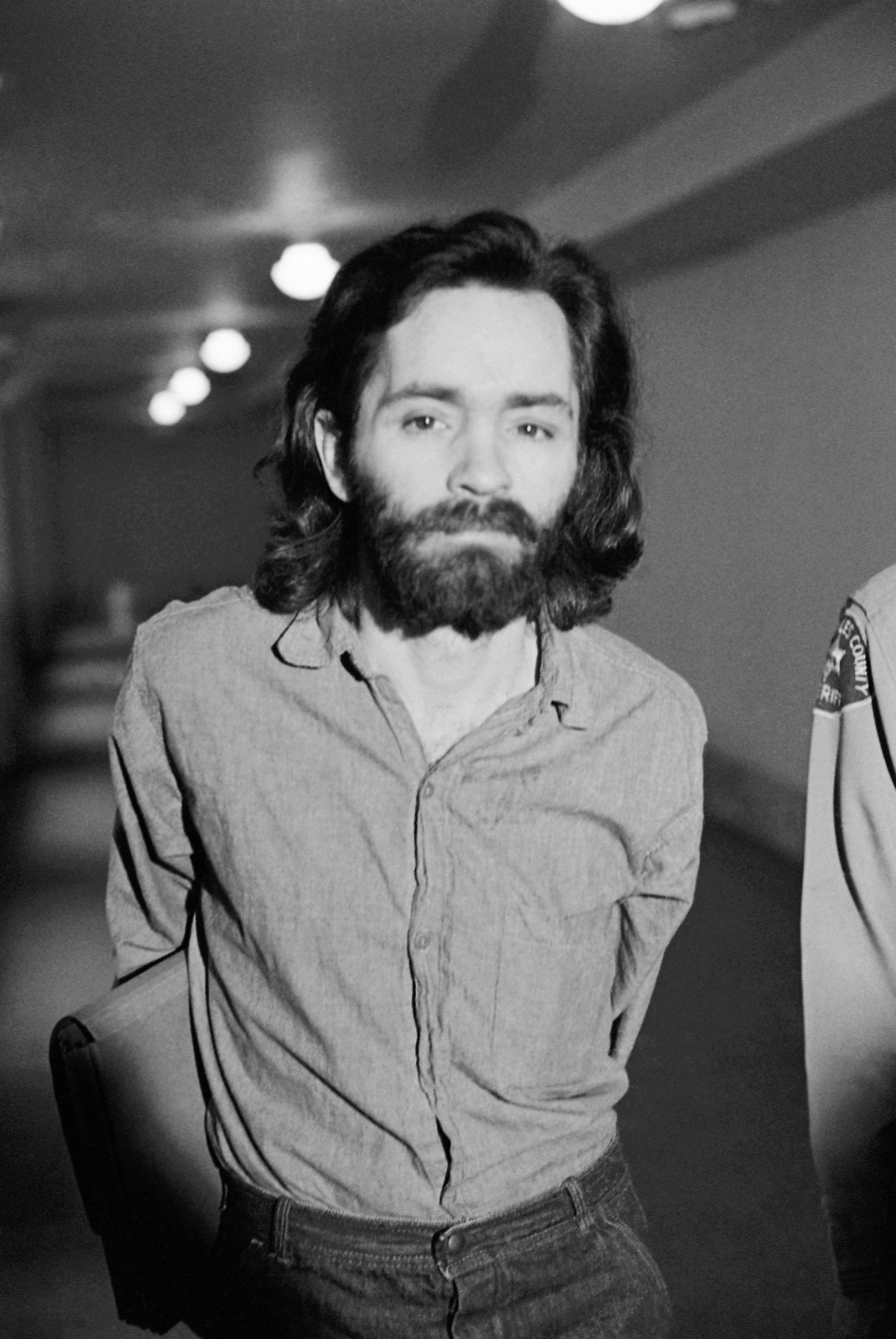

Pop culture is still in the thrall of Charles Manson’s death cult

As a serial killer, Charles Manson, who died Nov. 19 at the age of 83, wasn’t particularly accomplished. Arguably, he wasn’t actually a serial killer. “Manson Family” members, not Manson himself, carried out the seven murders the cult was responsible for and Manson’s two other murder convictions seem to have been more for business than pleasure.

As a serial killer, Charles Manson, who died Nov. 19 at the age of 83, wasn’t particularly accomplished. Arguably, he wasn’t actually a serial killer. “Manson Family” members, not Manson himself, carried out the seven murders the cult was responsible for and Manson’s two other murder convictions seem to have been more for business than pleasure.

Somehow though, Manson’s blend of infamy, sex, and death has come to define the way murder is portrayed in both pop culture and media. He has inspired books, documentaries, podcasts and television series. Manson tee-shirts, bearing his cartoonishly crazed stare with slogans such as “Charlie Don’t Surf” and “Never Trust a Hipster,” were in circulation even before Axl Rose donned one in the early 1990s. Quentin Tarantino has a biopic in the works. Not bad for a convicted murderer, cult leader, and vicious racist who carved a swastika into his own forehead.

Manson wanted to be a rock star and the Family shacked up with Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson for a time. In a sense, he became one, tapping into a deep well of fascination with grisly, ritualistic death that still pervades pop culture, despite the fact that the era of the serial killer has come and gone.

Right now we’re likely dreaming up more serial killers than actually exist. Must-watch television series over the past few years have included high-end American productions such as Hannibal, Mindhunter, Dexter, and True Detective, along with British shows including The Fall, Dark Angel, and In Plain Sight. Serial killers have also figured prominently in weekly procedurals such as CSI, Law & Order: SVU, and of course, Criminal Minds.

I’ll be honest—I’ve watched most of these shows. Based on them, you’d think serial killers and abductors are lurking around every corner. And indeed that exact—unfounded—fear has helped create a generation of children who are overprotected to the point of absurdity.

If you look at the Radford University/Florida Gulf Coast University Serial Killer Database, which tracks close to 4,800 serial killers and 13,000 victims over the course of more than a century, it’s clear the the 1970s-1990s were peak serial killer times. In 1969, when the Manson Family committed the Tate-LaBianca murders, the database estimates that 90 serial killers were active the in US. By 1977, the setting of the recent Netflix series Mindhunter, which depicts the rise of the Behavioral Analysis Unit at the FBI, that number rises to 201. When Silence of the Lambs, perhaps the loftiest entry in the serial killer canon, swept the Oscars in 1991, it was at 238. But by 2015, when Aquarius, a rather tedious NBC show staring David Duchovny as a detective tracking Manson premiered (before being canceled after two seasons) the confirmed number of active serial killers had fallen to just 45.

This reveling in serial killer mythology isn’t just harmless entertainment. With its exploration of ritual murder, child abduction, and mass shootings, it encourages an understanding of violence as a dramatic act of evil. But the fact is, violent crime has fallen dramatically in the US during the time that Manson has been locked up. There are lots of theories for this, which range from policing strategies to lead reduction in gasoline to access to abortion and birth control.

Serial killers—and even mass shooters—are the outliers, statistically speaking. Most violence and assault happens close to home. Physical and sexual child abuse is far more commonly perpetrated by someone a child knows than any kind of stranger danger situation. More than half of mass shooters have a history of domestic violence.

And the demographics of most of the real victims of violence and crime aren’t reflected in these TV shows and movies—which truck heavily in tired “damsel in distress” tropes and often tug the audience’s heartstrings with storylines featuring children in mortal peril. In fact the victims of gun violence are overwhelmingly black men. People struggling with mental illness are much more likely to harmed, or to harm themselves, with guns than to harm others.

If we actually want to understand and address crime, it might be best to let our fascination with serial killers, and the highly dramatic brand of violence they represent, die with Manson—after season two of Mindhunter is released, perhaps.