The Codex Quetzalecatzin, a 400-year-old Mesoamerican map of Spanish colonization, is now online for all to see

The Codex Quetzalecatzin, a manuscript dating back to the late 1500s, sounds like an artifact from an Indiana Jones movie. Essentially an ancient map of an area including present-day Mexico City and Puebla, it was created during a period when both Spanish colonizers and indigenous people were using maps to lay claim to their land.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin, a manuscript dating back to the late 1500s, sounds like an artifact from an Indiana Jones movie. Essentially an ancient map of an area including present-day Mexico City and Puebla, it was created during a period when both Spanish colonizers and indigenous people were using maps to lay claim to their land.

For centuries, the Codex was in the hands of private owners, including media magnate William Randolph Hearst. The US Library of Congress, which recently acquired the Codex (also known as the Mapa de Ecatepec-Huitziltepec) from French collectors, has now digitized it, making it viewable to the general public for the first time, online.

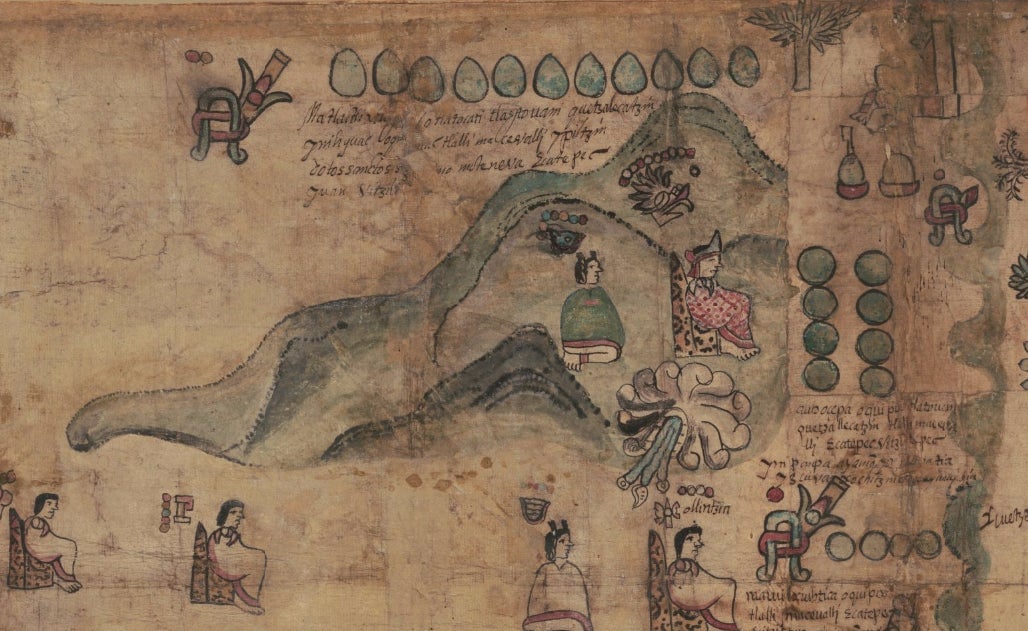

According to the US Library of Congress‘ John Hessler, clues in the map such as the symbols for roads and rivers, naturally extracted colors such as “Maya Blue” and cochineal (an insect-derived red), and Nahuatl hieroglyphics all point to indigenous authors. Hessler writes that it’s not only its rarity and good condition that make the Codex special, but also its depiction of a land in transition:

It depicts a local community at an important point in their history. On the one hand, the map is a traditional Aztec cartographic history with its composition and design showing Nahuatl hieroglyphics, and typical illustrations. On the other hand, it also shows churches, some Spanish place names, and other images suggesting a community adapting to Spanish rule. Maps and manuscripts of this kind would typically chart the community’s territory using hieroglyphic toponyms, with the community’s own place-name lying at or near the center. The present codex shows the [Spanish] de Leon family presiding over a large region of territory that extends from slightly north of Mexico City, to just south of Puebla. Codices such as these are critical primary source documents, and for scholars looking into history and ethnography during the earliest periods of contact between Europe and the peoples of the Americas, they give important clues into how these very different cultures became integrated and adapted to each others presence.

As Hyperallergic’s Allison Meier wrote, the week of the US’s Thanksgiving holiday, which also highlights European arrival in the Americas, makes a poignant moment for sharing a historical document of colonization with the viewing public.