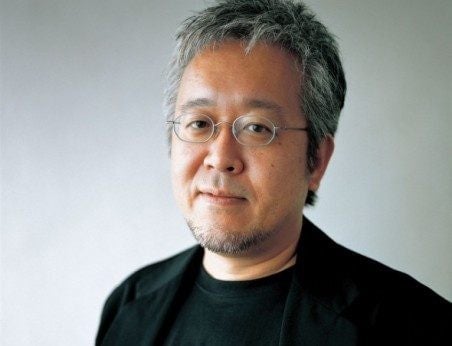

Emptiness—not minimalism—is the path to creativity, explains MUJI’s design philosopher

For the past decade, MUJI’s preeminent art director Kenya Hara has been traveling the world to spread his philosophy of emptiness. At a time when we’re bombarded by the 24/7 news cycle, back-to-back appointments, and the ceaseless stream of beeps and vibrations from the phones in our pockets, Hara’s message on the virtue of utter blankness has never been more appealing.

For the past decade, MUJI’s preeminent art director Kenya Hara has been traveling the world to spread his philosophy of emptiness. At a time when we’re bombarded by the 24/7 news cycle, back-to-back appointments, and the ceaseless stream of beeps and vibrations from the phones in our pockets, Hara’s message on the virtue of utter blankness has never been more appealing.

Hara’s recent visit to New York City coincided with the brand’s 10th anniversary in the US. Speaking in a subterranean lecture hall in the frenetic Times Square district, Hara delivered a mesmerizing meditation on the founding tenets of the Japanese brand that has elevated the world’s understanding of generic goods.

“Emptiness is a creative receptacle,” Hara began, making a point of distinguishing it from simplicity or minimalism. Instead of a system for shedding elements or clearing up spaces, like the one advocated by another Japanese sage, Marie Kondo, emptiness or ku is a more fundamental state of being.

Ku is not a poverty or absence of ideas or materials. Indeed, it’s a much richer concept than the Western understanding of “emptiness.” It’s a stance—a readiness to receive inspiration from outside. “To offer an empty vessel is to pose a single question and to be wholly ready to accept the huge variety of answers,” says Hara. ”Emptiness is itself a possibility of being filled.”

Hara went on to explain this Japanese amour vacui in terms of MUJI’s devotion to multi-purpose generic goods. Instead of naming a product with its intended purpose—like, “coffee table”—MUJI prefers open-ended labels such as “oak table.” This gives users the creative freedom to designate the table’s ultimate purpose.

Applied to product design, “emptiness” is a treatise against over-engineered objects. To illustrate the point, Hara compared two kitchen knives—a sleek, Henckels ergonomic chef’s knife from Germany, and the basic Yanagiba knife preferred by Japanese master chefs. The German knife anticipates the user’s grip, giving the thumb a natural place to rest, but Japanese chefs prefer a less programmed tool, to hold as they want. “A flat handle is not seen as raw or poorly crafted,” Hara explained. “On the contrary, its perfect plainness is meant to say, ‘You can use me whichever way suits your skills.” The Japanese knife adapts to the cook’s skill, not a cook’s thumb.”

There’s also a mental way to channel this emptiness, which involves having the humility to listen to foreign ideas, Hara said, explaining, “Questioning is emptiness.”

“To create is not just to create objects,” he explained. “Coming up with a question is also creation—the very essence of a question is its power to elicit the possibilities of reply, to collect a variety of thoughts… I believe that the richness of thinking may be the critical resource needed to give this world a future.”