As young Chinese get hooked on hip-hop, streetwear sees a boom

Chinese label CLOT’s runway show at New York Fashion Week was neatly embodied in a single soccer jersey. On one side sprawled a dragon, on the other a Nike swoosh.

Chinese label CLOT’s runway show at New York Fashion Week was neatly embodied in a single soccer jersey. On one side sprawled a dragon, on the other a Nike swoosh.

The show was meant to bridge East and West, and to show off Chinese fashion talent to an American audience. In a collaboration with Nike, Air Force 1 sneakers were redone with ornate silk uppers that took inspiration from traditional Chinese textiles. At the core of the show, meanwhile, were the baggy pants, bomber jackets, and flannels that are staples of streetwear, an amalgam of skate and hip-hop cultures exerting a growing influence around the world.

The Feb. 7 presentation was part of Tmall China Day, a new partnership between China’s biggest e-commerce platform, the Council of Fashion Designers of America, and Suntchi, a prominent management firm in China’s fashion and entertainment business. Sports brand Li-Ning showed in the morning, followed by Peacebird, a large Chinese contemporary label, and Chen Peng, a young designer brand.

CLOT was arguably the main event. A number of prominent influencers came out for the show, or walked in it. Had the event happened just a few years ago, though, it’s questionable whether CLOT would have been asked to show at all. Streetwear has been around in China for some time: CLOT’s show—its New York Fashion Week debut—doubled as a celebration of its 15th anniversary. But it hasn’t been a major force in Chinese fashion until much more recently. Young Chinese are quickly discovering it, in large part because of the sudden rise of hip-hop in China—another meeting of East and West.

“I think streetwear is the next thing in China right now,” Edison Chen, the Canada-born Hong Kong entertainment star who cofounded CLOT with his friend Kevin Poon, said backstage after the show. “I think a lot of big companies are attaching themselves to it, whereas before they’d be kind of shunning us. It’s growing exponentially right now.”

Hip-hop in China

Jessica Liu, president of fashion and luxury at Tmall, which is the largest business-to-consumer platform in Asia and is owned by Alibaba, said the platform introduced streetwear brands three years ago, but the real explosion came last year. “In particular because there’s a new popular TV show that’s about hip-hop,” she said. “It’s gaining a lot of traction with young Chinese.”

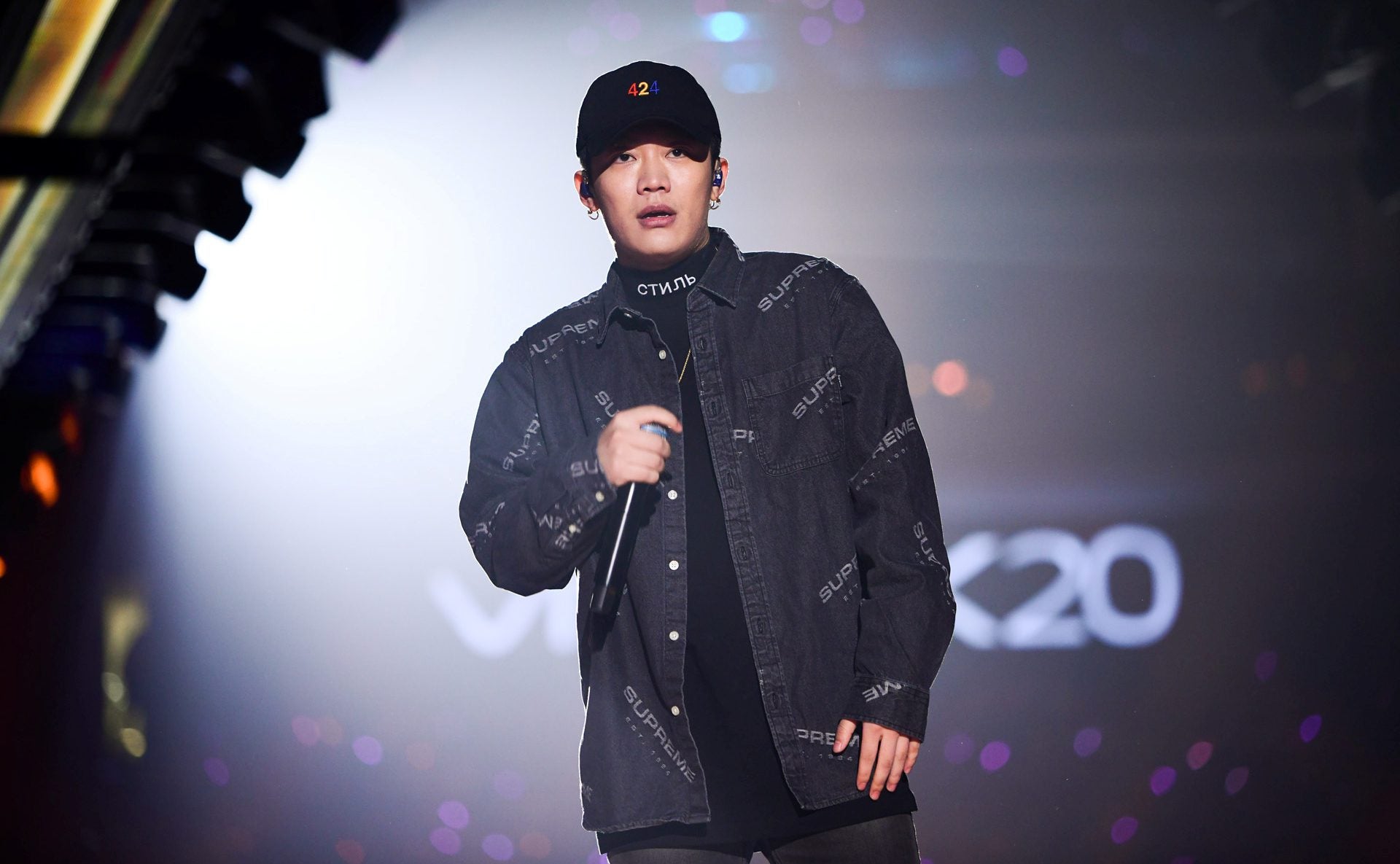

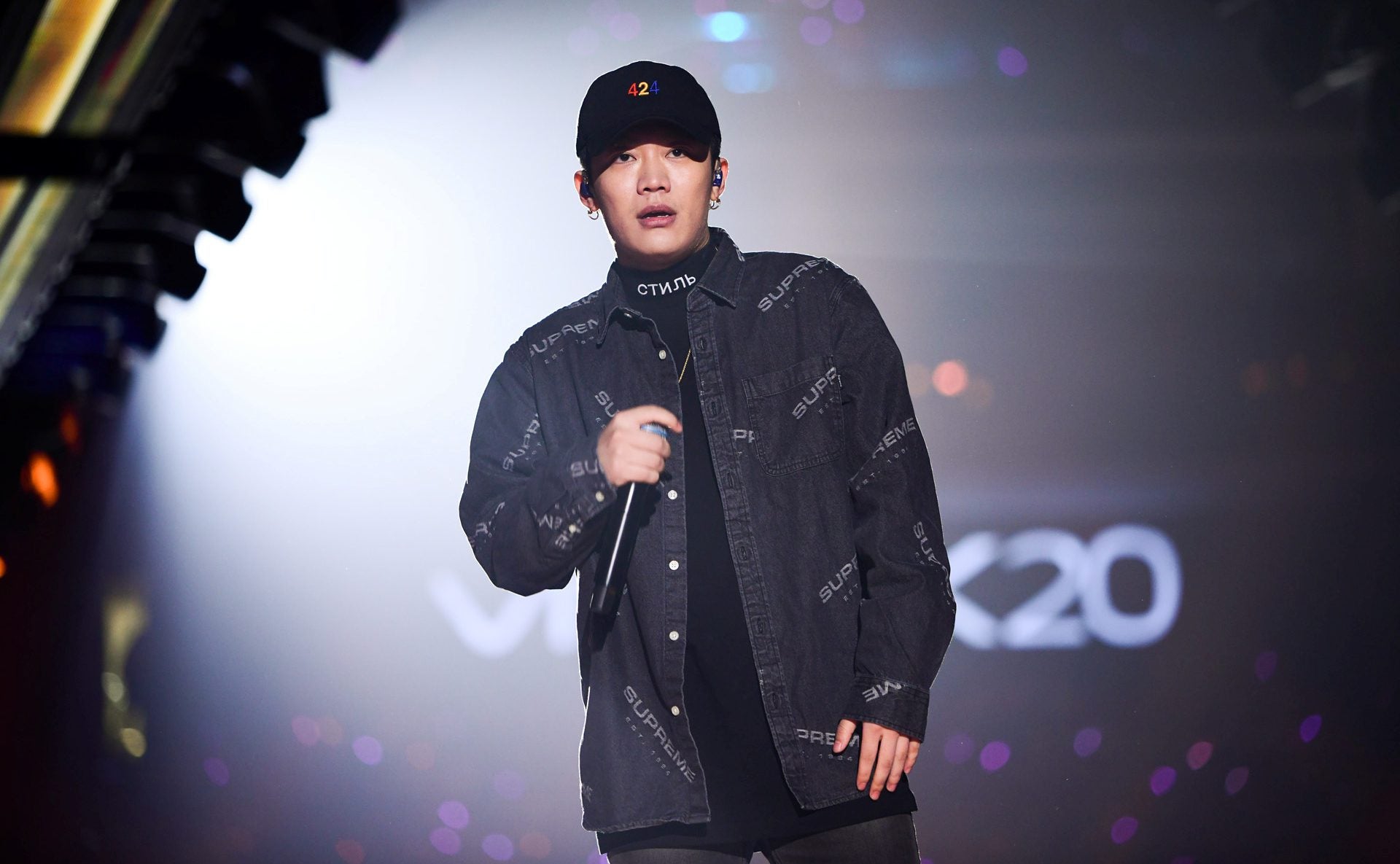

The show, The Rap of China, is a reality series where four celebrity producers coach fledgling rappers through rounds of competition. It has been a phenomenal success since its June 2017 debut on IQiyi, the video-streaming platform from the Chinese search giant Baidu. In just its first month, the show racked up more than 600 million views, and each episode is widely talked about on social platforms such as Weibo.

For hip-hop in the world’s most populous country, it marks a turning point. The genre has been accumulating fans since the 1990s, but even so it has remained basically an underground art form. The government kept a wary eye on it, concerned it might promote the wrong values for good Communist youth, and has gone so far as to ban songs in the past for “promoting obscenity, violence, crime or threatening public morality.” An assault on hip-hop by Chinese state media started recently after one of The Rap of China‘s winners, PG One, drew official ire over unsubstantiated allegations that he slept with a married celebrity.

The Rap of China has put hip-hop squarely in the spotlight, and brought streetwear along with it. The music has deep ties to streetwear, and had a formational influence on core streetwear brands such as Stussy, A Bathing Ape, and Supreme. On the first episode of the show, Kris Wu, the actor, singer, and Chinese megastar who is one of the show’s celebrity producers, wore a box-logo t-shirt by Supreme.

Plenty of other international brands have featured prominently as well, getting exposure to its massive viewership. One of these is Off-White, the fashion label by American designer Virgil Abloh with pronounced streetwear influences. “Many high-profile contestants chose to wear Off-White’s hoodies, pants and hats while performing,” Jing Daily reported. “Its signature black-and-white striped pattern and textual adornments immediately left an impression on Chinese audiences.”

The streetwear boom

Chen, of CLOT, got caught up in his own controversy in China some years ago, after he dropped off his computer for service and the technician leaked more than a thousand intimate photos of Chen with female celebrities. The scandal was major news across the country. Chen laid low for some time, but has lately been working to push CLOT onto a bigger stage. He and Poon have been doing pop-ups in cities such as Paris and New York, where CLOT will promote its collaboration with Nike.

CLOT is one of the top streetwear labels on Tmall, Liu says, and the category overall is flourishing. ”Their growth rate is like 60% higher than your average category growth,” she says of streetwear on the site. Most are men’s brands, and they include foreign as well as Chinese labels. Some of the top sellers, Liu says, are Aape, the more affordable offshoot of Japan’s A Bathing Ape focused on younger customers; Superdry, a British brand that blends Americana and Japanese elements, often a bit haphazardly; and Trendiano, a homegrown Chinese label. Sneakers and hoodies are popular.

Streetwear didn’t just materialize out of nowhere in China. Yoho!, the Chinese youth culture empire, has been a major force pushing streetwear (paywall) for some time. Its signature trade show, YO’HOOD, has quickly grown into a massive event since its launch a few years ago. Brands such as Sankuanz, a Xiamen-based label that has recently started getting international attention, have been at work for years.

The rise of hip-hop has helped push them into the foreground finally. But there are other factors giving streetwear a boost.

China’s young shoppers

The big force driving streetwear is youth culture. There are more than 400 million millennials in the country, and their tastes aren’t like those of previous generations. They want unique, niche brands that offer them a way to show off their identities, and they are influenced by (paywall) celebrities and what are known as key opinion leaders, or KOLs (basically what the US calls “influencers”).

These young people also have a lot of disposable income. One effect of China’s one-child policy, which lasted from the late 1970s until 2015 (paywall), was to create a lot of households with two parental incomes, and just one child to spend it on. Add in up to four grandparents, and the fact that many young Chinese don’t move out of the house until they’re earning enough and in a serious relationship, and the result is a generation with a lot of access to money.

China’s luxury shoppers tend to be much younger than their Western counterparts as a result. Bain & Company estimates that the average age of Chinese luxury shoppers is about 35, a decade younger than the average in Europe. Others say the gap is even wider and still growing, which fits with what Liu says she sees on Tmall. “In China, especially on our platform, the age range is 25,” she explains.

Streetwear’s ties to youth culture make it an obvious draw for these shoppers, and that holds true beyond Tmall, too. Bain & Company has also found that China’s millennial luxury shoppers—like those in the West—are less interested in traditional status symbols such as Prada handbags, and more in sneakers, t-shirts, and other streetwear staples. In fact, one of the reasons floated to explain why the famously insular label Supreme accepted outside investment is to allow it to expand into China (paywall), where an eager audience awaits.

All the ingredients are there for streetwear to continue growing in China. At CLOT’s show, Chen expressed his gratitude for the support he’s gotten from brands such as Nike and Converse. “With these collaborations, more and more people know our brand. Now with this show, hopefully it pushes it to a higher level,” he said. “We’re really humbled by this experience. We’ve been doing this for 15 years. Never did we think we’d come to New York Fashion Week.”