The many layers of meaning in Barack and Michelle Obama’s official portraits

Washington, DC

Washington, DC

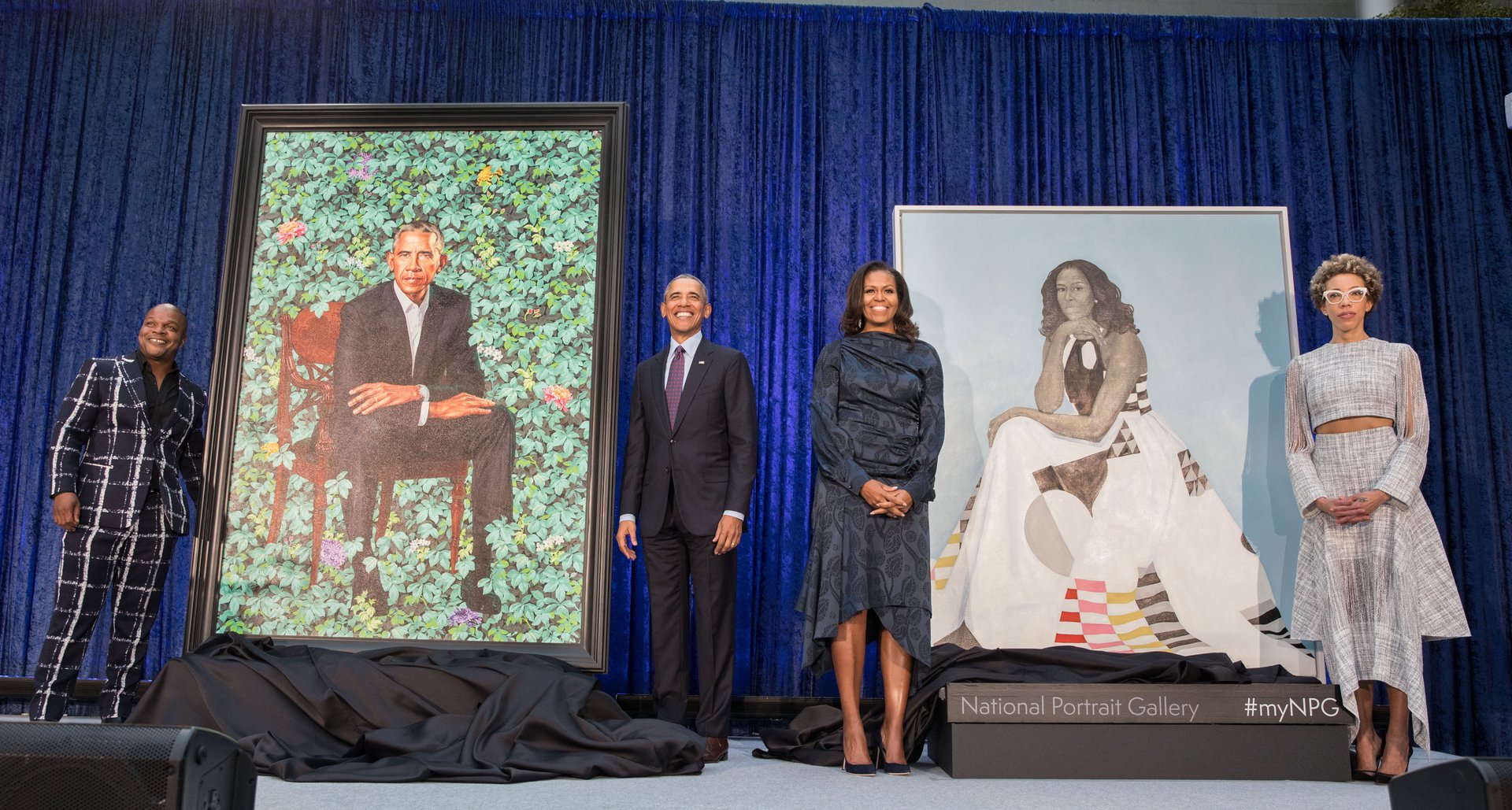

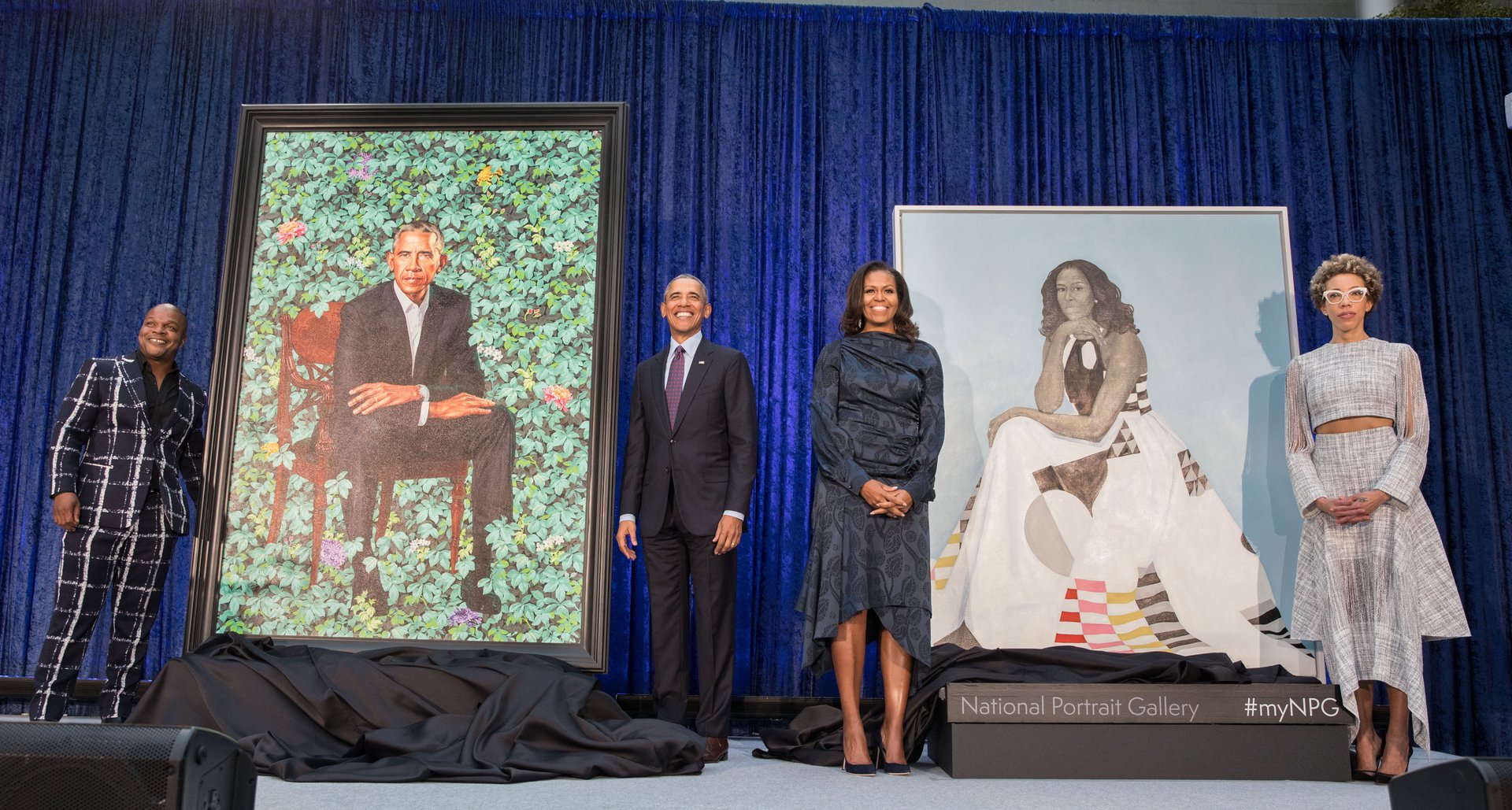

A presidential portrait is a fertile occasion for metaphor. And as the official portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama spread across social media yesterday, the reactions to the extraordinary paintings were freighted with emotional and historical significance.

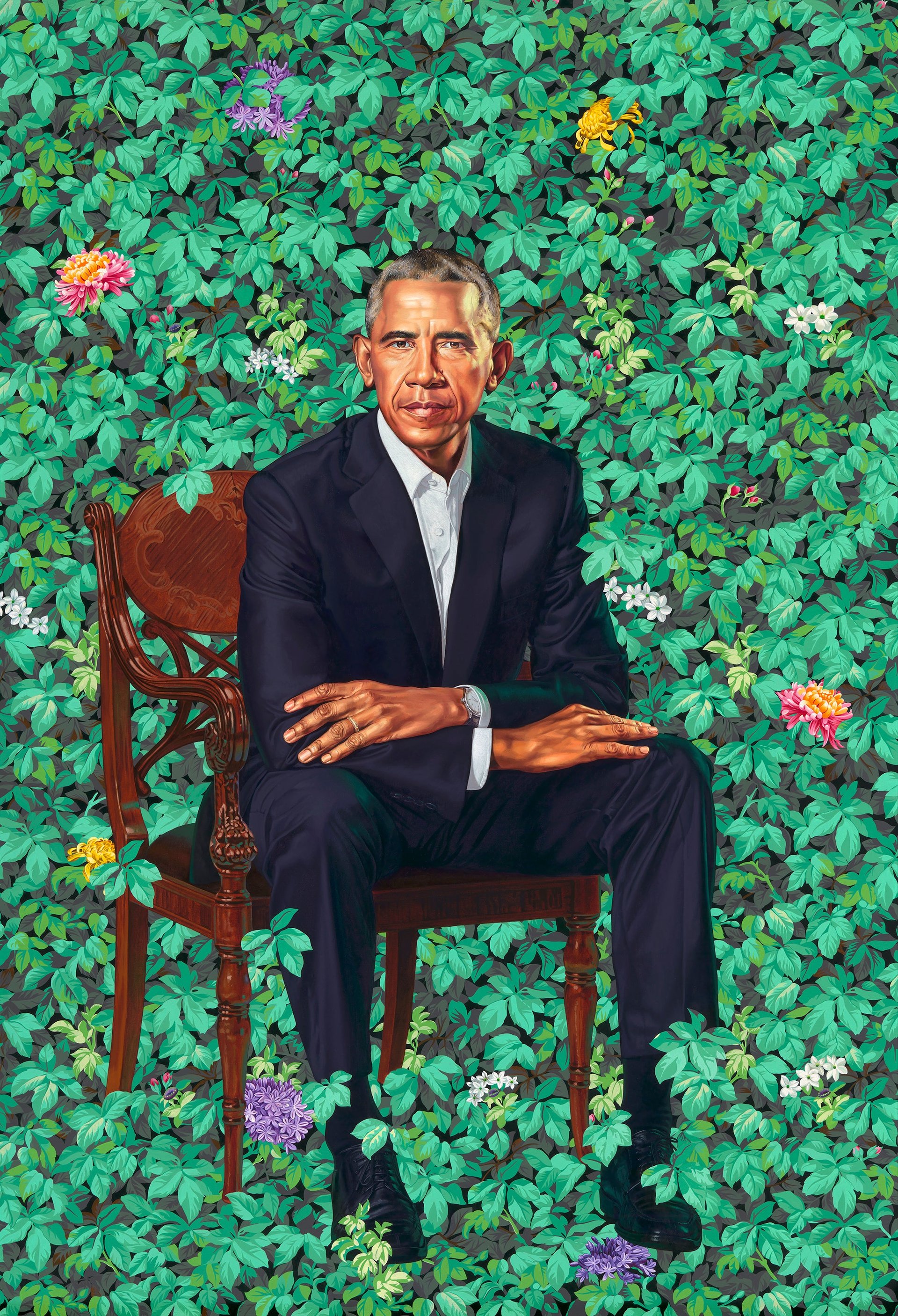

In person, the actual paintings convey additional layers of meaning. The Obamas’ official Smithsonian portraits are striking and modern but also nod to an established rule of political portraiture: symbolism.

Celebrated portraitist Kehinde Wiley depicted the 44th US president in a pensive pose, engulfed in flowers from three places in his biography: jasmine for Hawai’i where he grew up, chrysanthemums for Chicago where his political career flourished, and African blue lilies for his late Kenyan father.

“How about that? Pretty sharp,” beamed the former president as he and Wiley pulled the cloth off the seven ft. tall painting, as a crowd of art world insiders, politicians, and Hollywood celebrities cooed in delight.

“In a very symbolic way, I’m charting his path on earth through those plants that weave their way,” explained Wiley. “There’s a fight going on between he and the foreground, between him and the plants trying to announce themselves underneath his feet. Who gets to be the star of the show? The story or the man who inhabits that story?”

In Michelle Obama’s portrait, a different symbolic approach

The first lady’s portraitist, Amy Sherald, is less overt with allegorical embellishments, but her subjects herself become symbols, as she presents them more as archetypes than individuals. ”My approach to portraiture is conceptual,” explains Sherald. “Once my paintings are complete, the models no longer exist as themselves. I see something bigger, more symbolic.”

In the first lady’s portrait, Sherald depicts Michelle Obama as the paradigm of a modern woman—”a human being with integrity, intellect, confidence and compassion,” as she puts it. “What you represent to this country,” she said, turning to Obama herself, “is an ideal.”

The Baltimore-based painter presents her subjects in monochromatic backgrounds, their bodies and faces depicted with a grey pallor and neutral expressions, explains Kathryn Wat, chief curator of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. ”Her work offers a much livelier take on portraiture,” says Wat. “It suggests that people are never of a singular personality and much more complex than we might ever imagine.”

Her pose, particularly the decision to show her famous arms, is also symbolic, expressing a quiet defiance, observes Quartz’s Nöel Duan: “The bare-armed portrait is a radical and defiant gesture to the critics who thought Obama was dressed too inappropriately for official state business. She looks serene, almost retreating into her billowing graphic-print gown, but her arms are bold, toned, and bare—a testament to the former First Lady’s 5:30am workouts and unwavering sense of self.”

Obama’s voluminous dress bears additional symbolic weight: The gown from the Milly spring 2017 collection in fact, comes with a sewn-in political agenda. Milly’s designer, Michelle Smith, told the Washington Post that the dress is designed to evoke a populist spirit. “People have been describing the dress as couture, but the fabric is a stretch cotton poplin,” she says. “It could be called a worker’s fabric.” The beauty of the dress, she tells the Post, is that it looks “like couture but it’s made out of something spartan.”

Sherald saw yet another level of symbolism, explaining that she chose the floor-length dress printed with bold, geometric patterns in part as a nod to the legendary group of black quilters from Alabama collective known Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers.

Of course, the Obamas’ historic selection of Wiley and Sherald, both stars in an art world where black artists continue to be sidelined, is meaningful. “The ability to be the first African American painter to paint the first African American president of the United States is absolutely overwhelming,” Wiley said at the ceremony yesterday. “It doesn’t get any better than that.”

And even the timing of the unveiling, on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, is deliberately symbolic. “What you may not know is that president Lincoln once credited a portrait for getting him elected,” said David Skorton, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, referring to the striking 1860 photograph taken by Mathew Brady on the day Lincoln gave his famous address at Cooper Union in New York City. Skorton also underscored the connection between Obama and Lincoln’s political paths. “It’s hard to believe that it was just eleven years ago when Barack Obama announced his candidacy in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois,” he noted. “Eleven years ago this very week.”

The symbolic power of political portraiture

But perhaps the biggest symbolic act is the Smithsonian’s practice of having an “official portrait” made in the first place. The tradition started only in 1994, with George H. W. Bush. A US president today has two “official portraits,” one for the White House and another for the Portrait Gallery.

Centuries ago, political portraits were amazingly effective tools of propaganda. The classic example is Hans Holbein the Younger’s 1537 portrait of Henry VIII. A strategic act of fiction, the German painter presented the feeble 45-year-old English king as a plumply robust, formidable alpha male, to assure his subjects of his good health and authority. That painting was copied multiple times and remains the Tudor king’s lasting image.

Of course, one oil painting today cannot define a politician’s legacy, as it did before the advent of digital photography and social media. Today it’s impossible to avoid the unceasing stream of images of political leaders going about their daily business. In the age of Instagram and 24/7 news cycles, the public gets to see their elected officials from many angles, so our perceptions are a composite of official and unofficial portraits.

White House photographer Pete Souza’s genius eye, and lens, gave the public a window into the Obamas’ private lives and inner sanctum. Who’s to say that the vast catalogue of Souza’s iconic and candid Obama images aren’t the former president’s most defining image? In fact, Souza took Obama’s official White House portrait, and was even present at the unveiling to documenting the event. Obama, who has admitted he has little patience for posing for pictures or extended sittings with a painter, is the first US president to opt for a digital photograph for his official White House portrait.

An official oil painting today is largely a ceremonial gesture, its efficacy limited to those who will encounter the paintings in a museum. Wiley’s and Sherman’s thrilling portraits transmit well on social media, but their emotional might truly radiates only when you stand before them at the Portrait Gallery.

The Obama’s new portraits will be on permanent view at the Portrait Gallery starting this week.