Instagram is killing the way we experience art

“Please take your photos as quickly as possible and you can look it up online. Everything is online.”

“Please take your photos as quickly as possible and you can look it up online. Everything is online.”

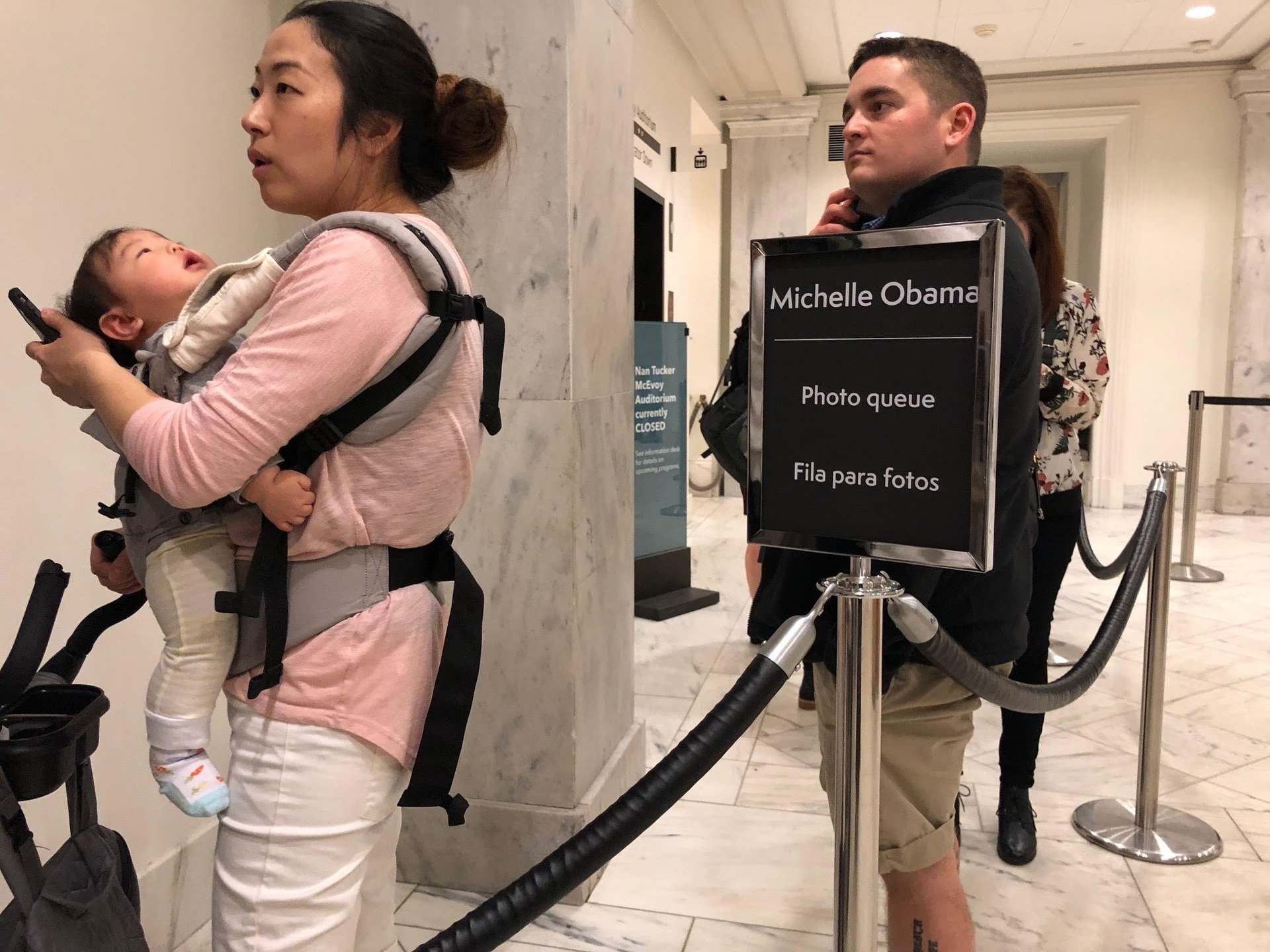

Those were the instructions of a museum guard to visitors at the US National Portrait Gallery last Thursday night. Since the unveiling of Barack and Michelle Obama’s official Smithsonian portraits on Feb. 12, hundreds have flocked to the Washington, DC museum—some queueing for hours—to get a few seconds in front of the much-talked-about paintings by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald. In an effort to expedite the lines, the Portrait Gallery has devised a cordoned “photo queue” system for anyone who wants to see the paintings up close.

Once in front of the portraits, most museum goers did one of three things: They held up their mobile phone to take a picture of the painting; they turned around to snap a selfie with the painting as backdrop; or they posed next to the portraits for a companion to take a souvenir shot (making the Obamas’ Smithsonian portraits into the world’s most expensive life-size cardboard cutouts).

What hardly anyone did was this: Raise their eyes from their mobile phone and use their allotted time to gaze up at the arresting, symbol-laden canvases.

Photo vs. no photo museums

It’s very strange way to spend a day: Waiting in line for hours to look at two paintings; only to stand in front of them, looking at them through the tiny screen of your phone—upon which you could easily have called up a million already existing photographs of the paintings.

And yet this behavior is not exclusive to the event of the Obamas’ portraits. It’s a scene that plays out around the world. Art museums and curators don’t seem to mind: Long gone are “no photos” signs. Craving social media exposure, museums like the Portrait Gallery not only tolerate photos, but actually encourage them.

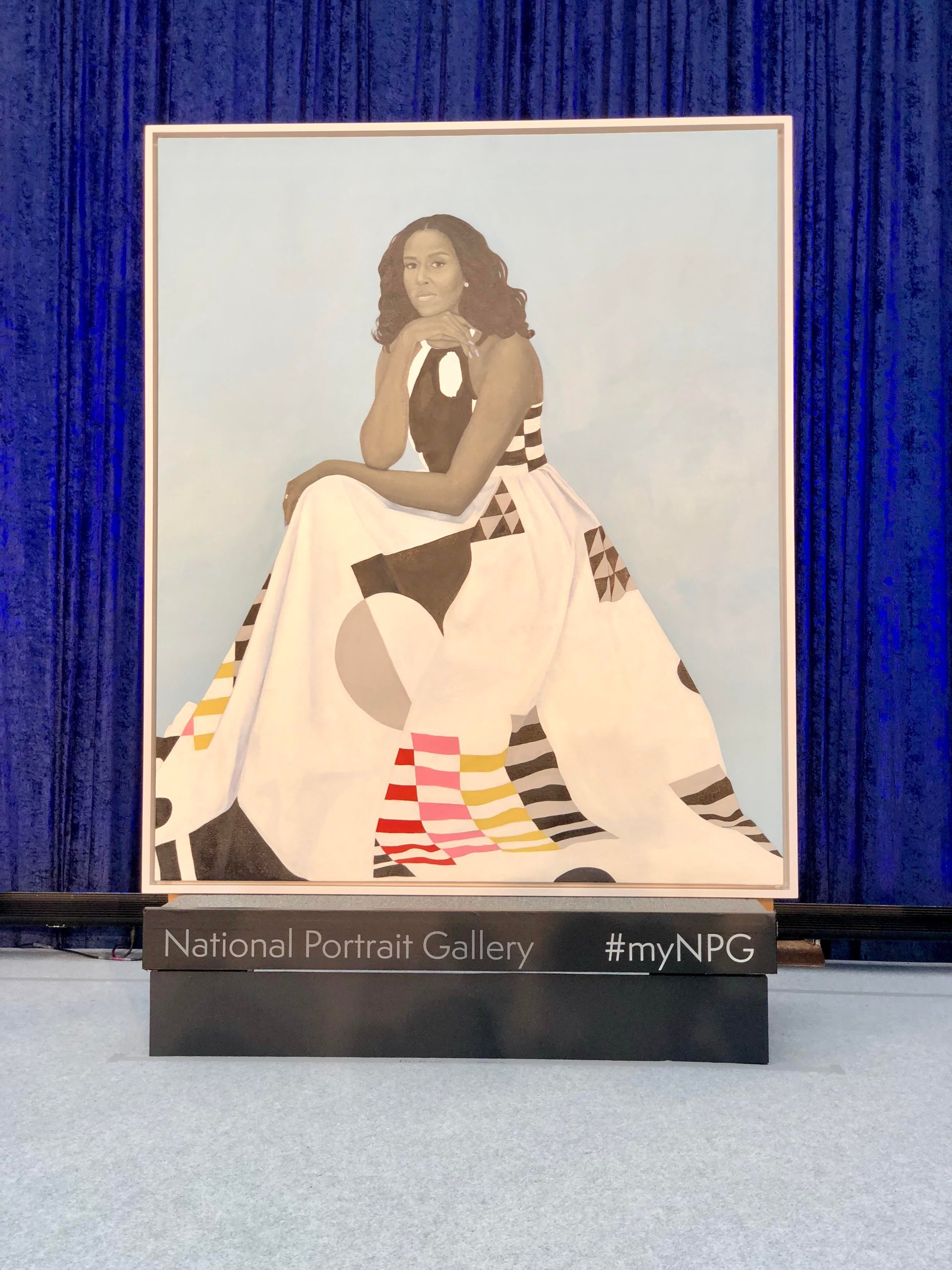

At the ceremonial unveiling of the Obama portraits last week, the Portrait Gallery’s announcer repeatedly nagged the crowd to share snapshots using the hashtag #MyNPG. The Obama portraits were propped up on platforms with the hashtag below it—essentially 3D models of an Instagram post.

This is a far cry from the time when art museums banned or just barely tolerated photo-takers. Many restricted cameras to shield light-sensitive materials or protect the copyright of the owners who loaned works to an exhibition. “You are fighting an uphill battle if you restrict,” Nina Simon author of The Participatory Museum, told ArtNews in 2013. It was around that time when Instagram began to permeate every aspect of modern life, and images of artfully arranged food, pets, and kids—as well as actual art—flooded social media feeds.

Curators have come to embrace social media as a way for visitors to engage with art, explains Dr Kylie Budge, a senior research fellow at Western Sydney University. “It tips the balance of power and makes the experience more democratic on some levels,” she says. “There’s an element of co-creation involved. With platforms like Instagram available, the person experiencing the art now has the capacity to respond and create something instantly that communicates their reaction.”

Of course, this curatorial shift has had some hazards: among them errant selfie sticks and overzealous photographers who bump into the art. The latest fiasco happened at the Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute. Michael Rohana, a 24-year-old from Delaware, put his arm around a 2,000-year-old Chinese terracotta warrior sculpture to take a selfie. He also broke off a thumb from the hand of the $4.5 million Qin dynasty statue as a souvenir. Museum guards have a lot more to watch out for these days.

Snap judgements

Are social platforms changing the way we judge art, or making us more easily dismissive? Put another way, does a work that an artist has labored over for months, even years, deserve more than a glance on a tiny screen?

As the images of the Obama portraits started streaming out, the reactions came hard and fast. Looking at art online feeds a coterie of casual critics, just as everyone’s a design critic with every new logo launch these days. Within minutes of the live-streamed unveiling, Twitter was ablaze with hot takes, critiques and memes.

A seminal 2001 study found that museum goers spent an average of 17 seconds looking at a work of art in a museum, with the bulk of time spent the reading the wall text. With social media, this time is probably even shorter.

There was a time when art lovers traveled great distances to see a work of art. For these pilgrims, a personal audience with genius was the goal. A museum was a place to hone one’s ability to detect beauty and appreciate nuance—with only our own internal filters between us and the work.

Platforms like the incredible Google virtual museum tours have eliminated the need to travel, by enabling art lovers to “visit” top museums and “see” works of art up close, at even higher resolutions than if they were to stand before it a museum.

But despite the democratizing value of widely disseminating great masterpieces, the fact is that looking at art on our backlit screens is not the same as encountering it in person. Take the work of the British painter J.M.W. Turner: To the casual Instagram swiper, his wild brushstrokes might seem unruly, even quaint. In person, even a smaller canvas like Peace – Burial at Sea is so arresting and emotional it’s impossible to ignore.

The same can be said about standing before Wiley’s hyper-realistic Obama portrait. The painting “pops” on the small screen, but in person a profusion of many sharp details leap at the viewer—the man’s expression, his wedding band, the surface of the chair, the individual flowers. Unconfined by the screen, one can see wonderful details like the electric green sheen on his knee and forearm.

Better Art Grams

If mobile phones are inevitable in museums—which increasingly they are—can social media actually enhance our experience of art? A hopeful picture emerges in a 2015 study Budge conducted at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney. She found that over 90% of Instagram posts were about details of the exhibit, not vanity selfies as most would assume. This suggested that most visitors had taken the time to see the real artifact and compose a thoughtful caption.

The answer isn’t to ditch your phone, or even check it in to the museum coatroom. Instead, try this: Put your smartphone in your pocket and stand before the work. Look at it, and allow yourself to get lost in it. Then, by all means whip out your phone, take a picture, and tell the world what you think.

Or, take a cue from Michelle Obama herself. Addressing the sea of cellphones raised in the air at the unveiling ceremony, the former first lady paused before starting her remarks.

“Let me just take a minute,” she said, turning to Sherald’s opus and looking up at it. “It’s amazing. Wow.”